Copyright cityam

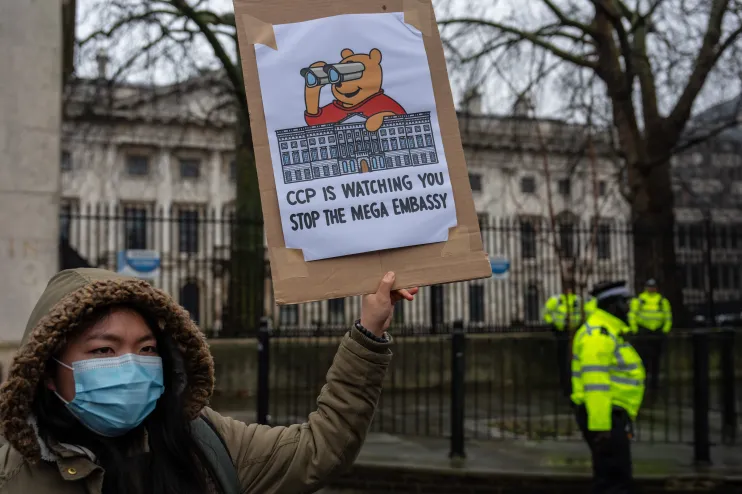

One day the story of China’s “super-embassy”, whether it is built or not, will be the subject of the kind of book-length investigative reporting that wins worthy prizes, writes Eliot Wilson Last week this paper reported that senior figures in the City of London Corporation were concerned about the new Chinese embassy which is proposed for Royal Mint Court near the Tower of London. The government of China bought the freehold on the 5.4-acre site in May 2018 for £255m, and local residents were first notified of the redevelopment plans in November 2020. This was not a bolt from the blue for Whitehall: quite the opposite. As foreign secretary (2016-18), Boris Johnson had appointed his ally Sir Edward Lister, then a non-executive director at the FCO, to lead negotiations with China over the purchase. This was the death rattle of the “Golden Era” of Sino-British relations, before the Chinese Communist Party’s brutal 2020 crackdown in Hong Kong. It is symbolic of Johnson’s later premiership that Lister was at the time also a paid consultant to CBRE, the property company acting for China, and to Delancey, the owners of the site. Sir Alistair Graham, the long-ago chairman of the Committee on Standards in Public Life, stated “the Foreign Office must investigate whether he [Lister] satisfied the seven principles of public life”. But that was akin to asking Guy Fawkes if his gunpowder was being handled safely: largely irrelevant and inadequate given the gravity of the issue. One day the story of China’s “super-embassy”, whether it is built or not, will be the subject of the kind of book-length investigative reporting that wins prizes. We should step back for a moment, however, and ask how and why we – how politicians, officials, advisers, the media and voters – ever got to this sorry stage. The Corporation did not raise new concerns last week but underscored an existing one: underneath the Royal Mint Court site are fibre optic cables which carry sensitive information to businesses in the City of London. One senior Corporation figure said “the cable issue is a concern and it does ring alarm bells that they’re pushing very hard for this particular site”, while Professor Sophia Economides of Northeastern University London told City AM “it’s very easy to tap into those cables, it’s very easy to see what’s happening – and it won’t be detected”. It would be a valid concern for the embassy of any country, friend or enemy, to be on a site so close to critical infrastructure. Under the Diplomatic Privileges Act 1964, the “premises of the mission shall be inviolable. The agents of the receiving state may not enter them, except with the consent of the head of the mission”. In other words, embassies are beyond the reach and jurisdiction of the host country. With malign intent, they are forward operating bases for our adversaries. We know China already spies on us, so the threat is clear. What beggars belief, and has convulsed the government over the recent collapse of the “China spy trial”, is the desperation of the verbal convolutions ministers and officials will employ to avoid saying what any sensible observer knows to be true: that China, a genocidal autocracy, is not our friend, does not wish the UK well and has aims and interests which are often directly in conflict with ours. We need not dig deep for evidence of this. For more than a decade, Beijing has stated that the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984, which formalised the handover of Hong Kong to China on 1 July 1997, no longer has any force or meaning – this despite its provisions that special arrangements for Hong Kong “will remain unchanged for 50 years”. The director general of the Security Service, Sir Ken McCallum, stated last week that “Chinese state actors present a UK national security threat… every day” and that his organisation has disrupted a case linked to China only days before. In July this year, he had detailed the range of ways in which the PRC threatened Britain, described it as a “massive” challenge and reiterated that “hostile activity is happening on UK soil right now”. A week later, Commander Dominic Murphy, head of the Metropolitan Police’s Counter Terrorism Command, told reporters that China, Russia and Iran were “increasingly… undertaking threat-to-life operations in the United Kingdom”. It sounds like a “daft laddie” question, but what more evidence do we need? China should be treated with extreme caution. This is not a call to send a gunboat up the Yangtze River or have Royal Marines seize Chinese ports; but there are gradations between that, such as not allowing the PRC to build Europe’s largest embassy on top of sensitive data cables or rubber-stamping heavily redacted construction plans. It is reported that the government regards trade and investment with China as “essential” to its growth plans at a time when the economy is expanding at a rate of barely one per cent. Unfortunately, ministers must choose: do they potentially jeopardise prosperity or national security? No formulation of words will protect both. The housing secretary should reject the embassy planning application when it comes before him in December, however much ire that provokes in Beijing, and China should be placed in the enhanced tier of the Foreign Influence Registration Scheme. This is neither provocation nor isolation, but a clear-eyed acknowledgement of the reality Britain faces. National security must come first. Eliot Wilson is a writer, senior fellow for National Security at Coalition for Global Prosperity and contributing editor at Defence on the Brink