If you’ve ever tried to end your Amazon Prime subscription, you may have found yourself embroiled in a disorienting multistep process that felt more like a choose-your-own-adventure than a simple cancellation.

The Federal Trade Commission is now taking Amazon to court over that cumbersome user journey, alleging that it was by design. The FTC claims that Amazon spent years knowingly trapping its customers in an endless Prime subscription—making cancellation so confusing that, per the agency, Amazon named the process the “Iliad Flow” after Homer’s 16,000-line epic poem.

The FTC’s lawsuit, which was first filed in 2023, alleges that Amazon “tricked” more than 40 million customers into enrolling in automatically renewing Prime subscriptions. It lays out in painstaking detail how Amazon knowingly used “dark patterns,” user interface tactics designed to dupe or confuse users, including its “Iliad Flow,” to coerce enrollment in Prime “without their consent” and to make it especially difficult to cancel Prime subscriptions.

As the trial kicks off, we take a deep dive into the Iliad Flow scheme at the center of the lawsuit, and how Amazon has capitalized off of similar dark patterns in the past.

Subscribe to the Design newsletter.The latest innovations in design brought to you every weekday

Privacy Policy

|

Fast Company Newsletters

The Amazon case as potential precedent

Dark patterns have become “typical industry practice” as major retailers and Big Tech companies use them to boost their bottom lines, according to David Carroll, a professor at the Parsons School of Design in New York who studies dark patterns and user data protection. But Carroll suggests the Amazon trial could set a new precedent. The FTC’s challenge is one of the broadest attempts to fight back against dark patterns that he’s ever seen, and it could have major ripple effects for how other companies design their user interface.

“Amazon is a unique sort of monopoly, so it has the ability to get away with the most egregious forms of dark patterns, which then sets the standard for the rest of the industry. Because if Amazon does it, why can’t we?” Carroll says.

The FTC’s updated court filing details exactly how some of those dark patterns functioned for Amazon between 2016 and 2023. For non-Prime customers, it explains, the company has a history of offering multiple “Prime upsells” before the final transaction. One page included a blue link near the bottom left of the screen, which in 2018 read “No thanks, I do not want fast, free shipping,” and in February 2020 read “No thanks, I do not want fast, FREE delivery.” This language is an example of what Carroll calls “confirmshaming,” or guilt-tripping designed to tug on users’ emotions.

Amazon’s dark pattern pièce de résistance was the “Iliad Flow,” the Prime-cancellation process that the FTC says Amazon changed in 2023 after the agency applied “substantial pressure” to the company. Per a Business Insider report in June 2023, multiple leaked internal documents showed that the cancellation process was dubbed “Iliad” by Amazon, and revealed that at some point in 2017 the Iliad Flow led to a 14% drop in Prime cancellations as fewer members navigated to the final cancellation page. Much like its namesake poem, the Iliad Flow involved a winding, complicated journey filled with frustrating stops and befuddling detours.

The convoluted journey indicates clearly how the flow represents a business-first rather than a user-first approach. Prime subscribers are some of Amazon’s most valuable assets. It’s estimated that Prime subscribers, who tend to buy more on the site than the average user, number somewhere close to 200 million. In 2024, those subscriptions netted Amazon $4 million.

That means Amazon has a lot of incentive to keep Prime subscribers around—and, Carroll explains, its intricate network of dark patterns is an example of using extensive A/B testing to engineer a system designed to keep customers trapped in its web.

advertisement

Business-first dark patterns

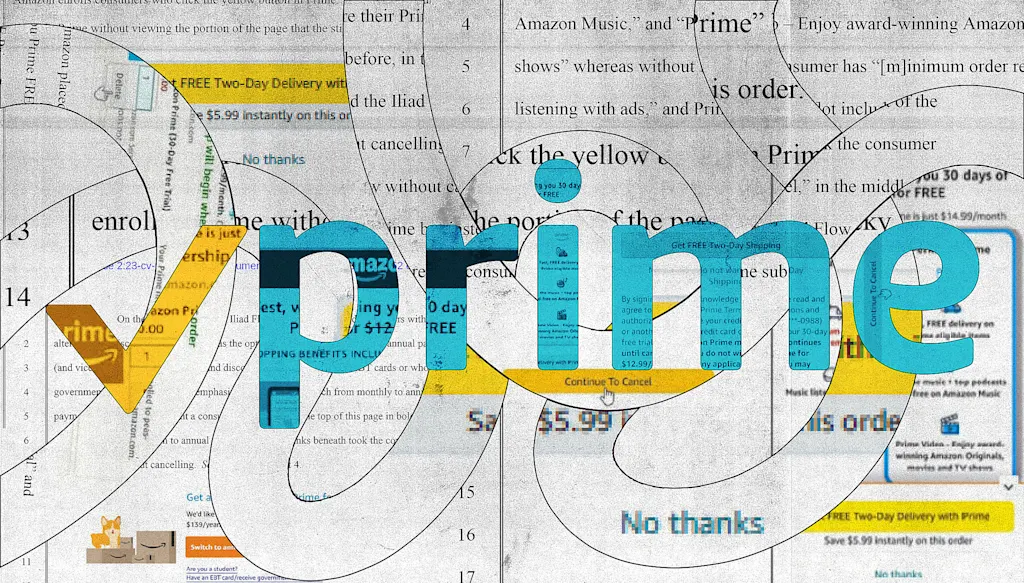

To cancel via the Iliad Flow (which the FTC referenced in its official report “Prime’s Four-Page, Six-Click, Fifteen-Option Iliad Flow”) a consumer “had to first locate it, which Amazon made difficult.” Things only got more confusing from there.

A user’s first trial was to make it through the initial cancellation page. Here, they were directed to look back at their previous Prime purchases and encouraged to click hyperlinks to services like Prime Video through calls to action like “Start shopping today’s deals!” At the bottom of the page, they would be presented with three options: “Remind Me Later,” “Keep My Benefits,” and “Continue to Cancel.” Every option except “Continue to Cancel” would boot users out of their intended flow and take them back to square one.

Those who chose “Continue to Cancel” were funneled on to page two, where they were presented with discounted pricing options and “exclusive offers” before once again seeing the same three-button prompt. And, like on the first page, “Continue to Cancel” was the only option that executed the user’s original intention.

On the third page of the Iliad Flow, Amazon showed consumers five different options, only the last of which, “End Now,” actually canceled the user’s Prime membership. Any of the other four buttons immediately ejected them from their intended process.

“When you go through this, you see how, not only is the Amazon ‘Iliad Flow’ designed to achieve its effect of preventing the unsubscription and to uphold the original nonconsensual enrollment, but the company internally knows that what it’s doing is, as the FTC says, ‘injuring customers,’” Carroll says. Yet, he adds, “there’s so much incentive for them to continue the practice.”

How the FTC challenge to “Iliad Flow” could change e-comm

Dark patterns like the Iliad Flow help Amazon bring new Prime customers in and keep them around as long as possible. In many ways, Amazon’s success has served as the blueprint for other online retailers to design their own dark-pattern webs. The FTC’s current challenge could show the broader retail climate that dark patterns are no longer going unnoticed.

“The FTC’s model as a regulatory system is to make examples of companies to dissuade other companies. The whole idea is, punish one so that the others also start behaving better,” Carrol says. “Because Amazon is such a massive target, I think we can’t underestimate the potential downstream effects.”

If the FTC wins this current case, Carroll says, it may send a message to smaller companies that there’s legitimacy to the consumer protection argument around dark patterns. It could even show that what Carroll describes as “internal discussions being diabolical about designing dark patterns” are, quite simply, bad for business.