Copyright The Boston Globe

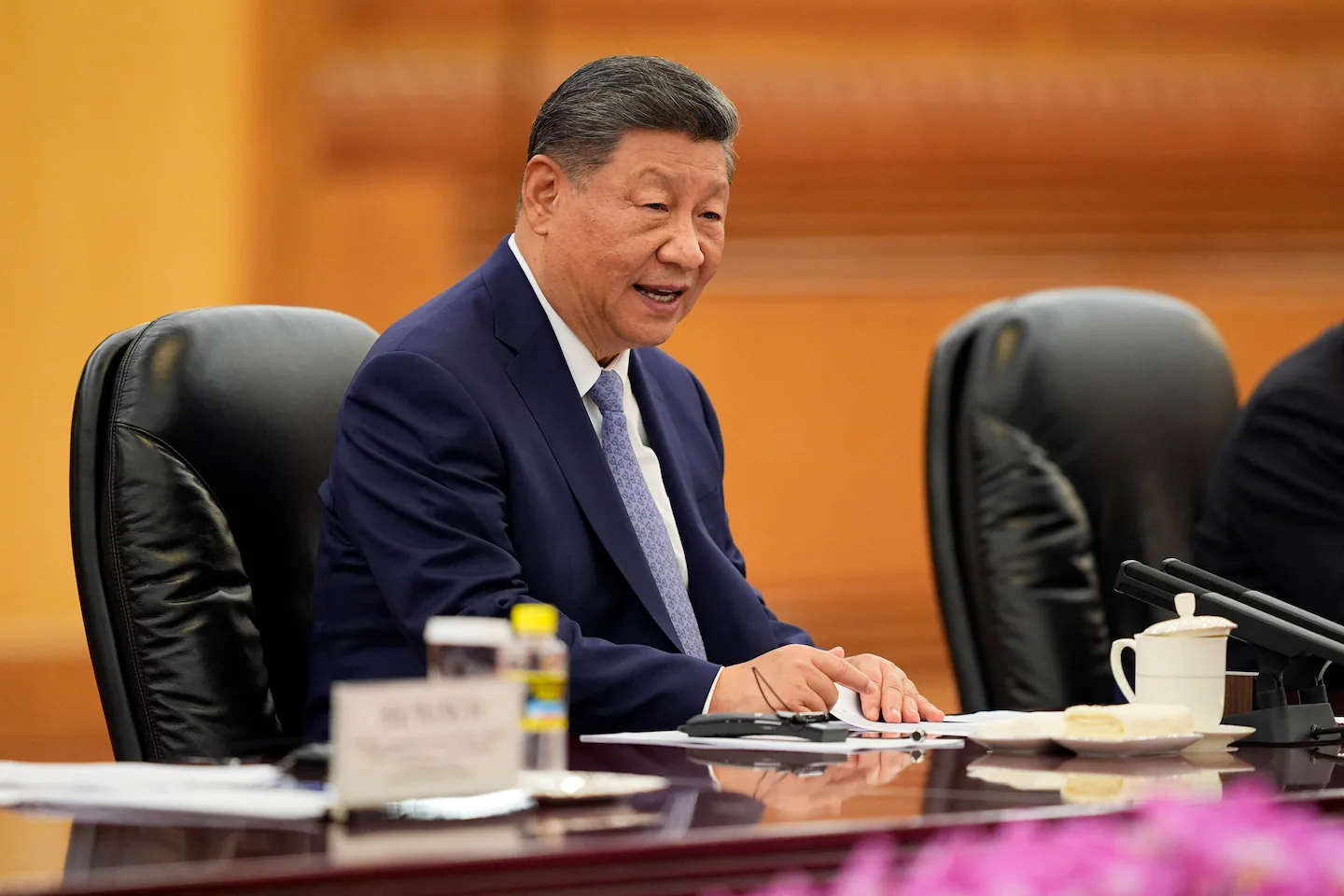

Xi faces a dilemma familiar to long-serving autocrats. Naming a successor risks creating a rival center of power and weakening his grip, but failing to settle on a leader-in-waiting could jeopardize his legacy and sow rifts in China’s political elite. And at 72, Xi will likely have to search for a potential heir among much younger officials, who must still prove themselves and win his trust. If Xi eventually chooses a successor, loyalty to him and his agenda will almost surely be a paramount requirement. He has said that the Soviet Union made a fatal mistake by picking reformer Mikhail Gorbachev, who oversaw its dissolution. On Friday, Xi made his intolerance for any disloyalty clear when the military announced that it had expelled nine senior officers, who face prosecution on charges of corruption and abuse of power. “Xi almost surely realizes the importance of succession, but he also realizes that it’s incredibly difficult to signal a successor without undermining his own power,” said Neil Thomas, a fellow at the Asia Society Policy Institute’s Center for China Analysis. “The immediate political and economic crises that he faces could end up continually outweighing the priority of getting around to executing a succession plan.” Speculation about Xi’s future is highly sensitive and censored in China, and only a handful of officials may be privy to his thinking about the issue. Foreign diplomats, experts and investors will be looking for clues from the four-day meeting of the Communist Party’s Central Committee that started Monday, bringing together hundreds of senior officials. The meeting, usually held behind closed doors in the specially built Jingxi Hotel in Beijing, is expected to approve a plan for China’s development over the next five years. Xi has made securing a global lead in technological innovation and advanced manufacturing a priority, and that goal is likely to feature heavily. He and his officials have expressed confidence that their approach can prevail over President Trump’s tariffs and export controls. “At the heart of strategic rivalry among the great powers is a contest for comprehensive strength,” senior Chinese lawmakers said in a report they issued last month on the proposed plan. “Only by vigorously upgrading our own economic power, scientific and technological strength, and overall national power can we win the strategic initiative.” For now, Xi seems convinced that China’s ascendancy depends on his continued stewardship. He bulldozed past the example of orderly retirement set by his predecessor, Hu Jintao, and abolished the presidency’s two-term limit in 2018, enabling Xi to stay in office indefinitely as head of the party, the state and the military. But each year that Xi stays in power, it becomes harder to find an heir who is both young enough to rule for decades and seasoned enough to command authority in his shadow. Xi has packed the Politburo Standing Committee — the seven-member body at the apex of party power — with longtime allies. They are in their 60s or older, likely too old to be plausible heirs several years from now, experts said. Xi was 54 when he joined the Standing Committee in 2007, a promotion that underlined his status as a favorite to become the next leader. Even officials poised to be elevated to central leadership at the next Communist Party congress, in 2027, are probably too advanced in age to succeed Xi, said Victor Shih, a professor at the University of California San Diego who studies elite politics in China. With Xi likely to serve another term or even longer, his successor could prove to be an official born in the 1970s, likely now working in a provincial administration or an agency of the central government. The party has been promoting some younger officials who fit that profile, said Wang Hsin-hsien, a professor at National Chengchi University in Taiwan who studies the Communist Party. But Xi also appears to be worried about officials who have not been tested by hardship or responsibility. He has warned that seemingly minor shortcomings in officials can become serious threats in moments of crisis — or, as he has put it, “A small crack can become a massive collapse” in a dam wall. “Xi is highly distrustful of others, especially those officials who have only an indirect relationship with him,” Wang said. “As he grows older and has fewer connections to the generation of his possible successors, this factor will become more important.” In the years ahead, the upper ranks of the party may grow more fluid as Xi tests and discards potential recruits for leadership, experts said. Behind the scenes, officials within his circle may jockey more intensely for influence and political survival. “This will make the succession process more fragmented, because he can’t possibly just have one designated successor,” Shih said. “It has to be a collective to choose from, and that probably also means they will have low-grade power struggles with each other.”