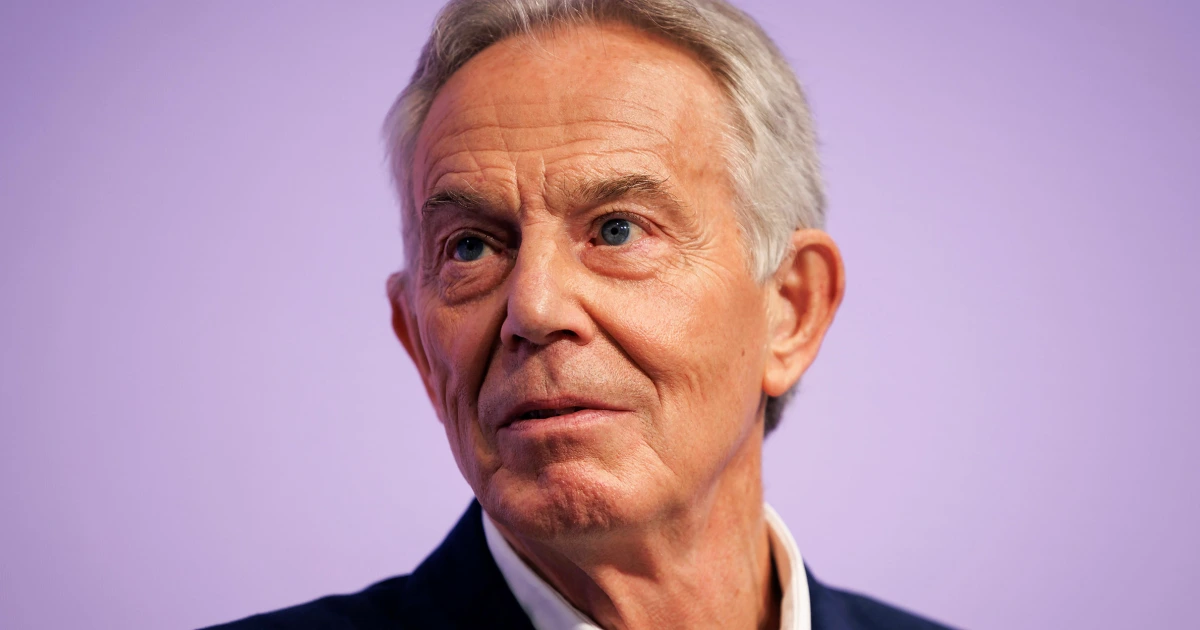

LONDON — Tony Blair.

A political titan who remains Britain’s most successful postwar leader, or a disgraced scourge of the Middle East who should never be allowed near the region again.

Depending on who you speak with, the man now set for a central role in President Donald Trump’s peace plan for Gaza could conjure either reaction.

The proposal will see Blair, 72, join Trump as co-chair of a “Board of Peace” — an international body that would oversee the reconstruction of the Gaza Strip after its devastation at the hands of the Israeli military.

Blair won three consecutive elections between 1997 and 2005, standing down two years later having never been defeated at the ballot box.

Some in Britain laud his landmark achievements such as introducing the minimum wage, pouring investment into public services and helping secure peace in Northern Ireland. But for many others, his name is a byword for the Iraq War, having used flawed intelligence to defy public opposition and join President George W. Bush in the 2003 invasion that is now widely viewed as disastrous.

Blair called Trump’s proposal “bold and intelligent,” saying in a statement it could “end the war, bring immediate relief to Gaza.” It brings the “chance of a brighter and better future for its people, while ensuring Israel’s absolute and enduring security and the release of all hostages.”

That came after Trump revealed Blair wanted to be on the board, calling him a “good man, very good man.”

Blair’s post-Iraq career includes a stint as global Middle East envoy, but even figures within his old Labour Party conceded that the potential appointment would “raise some eyebrows,” as its serving Health Secretary Wes Streeting told the BBC on Tuesday.

Indeed, among Palestinians, the reaction “is not positive, to say the least,” according to H.A. Hellyer, a senior associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute, a think tank based in London. “Blair continues to be associated in the public consciousness with the Iraq War.”

He’s a leader with “a lot of baggage, obviously,” agreed Michael Wahid Hanna, the U.S. program director at the International Crisis Group. “It’s just utterly peculiar as to what he’s doing here,” he said. “I think a lot of people are confused by that.”

Blair remains one of the most divisive names in British politics, despite having left the stage almost 20 years ago.

He roared into public view in the 1990s, winning the Labour Party leadership contest after the sudden death of his predecessor, John Smith.

He set about making radical changes, scrapping the left-wing party’s commitment to public ownership and sparking a bitter debate between those who saw this as the pragmatism needed to win elections, or the abandonment of progressive values.

After a historic landslide in 1997 that ousted the long-ruling Conservative Party, he set about remaking Britain with the minimum wage and Northern Irish peace, but also in landmark laws advancing LGBTQ equality and the social safety net.

None would define his legacy like following Bush into Iraq, however. Like in the United States, it still unites many conservatives and liberals in their (in some cases retroactive) opposition and revulsion.

The Iraq War saw Blair’s premiership end in 2007 under a cloud of anger — and, from the most vehement critics, accusations that he was a war criminal after hundreds of thousands of people died in the conflict that was not sanctioned by the United Nations Security Council or in accordance with the U.N.’s founding charter.

A landmark British 2016 inquiry found the basis for going to war was “far from satisfactory.” After that chastening conclusion, Blair expressed “sorrow, regret and apology” and took “full responsibility without exception or excuse” for the war’s tragic consequences. He said he went to war in “good faith,” believing the threat of Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction to be real and wanting to rid the Iraqi people of the “evil” of Saddam Hussein.

NBC News has contacted the White House and Blair’s office for comment on the criticism surrounding his proposed appointment.

Blair’s involvement with the Middle East did not end with the war.

On the day he stepped down, he announced he was to become special envoy to the Quartet, a supranational group comprising the United Nations, the United States, the European Union and Russia, which sought a resolution between Israel and the Palestinians. He resigned in 2015 having made little headway.

The next year, he founded the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, which has grown into a behemoth of more than 800 staff in some 40 countries.

The nonprofit institute has been criticized for working with authoritarian governments such as Saudi Arabia and Rwanda. Blair has previously defended his work in these countries by saying his institute focused on positive forces for change, even if those were in countries with imperfect human rights records.

At the head of this institute, Blair has continued to cultivate strong networks from the Middle East to Washington, and has reportedly been involved in backchannel discussions over Gaza in the past year.

Whatever his credentials, the idea of Western leaders parachuting in to govern Gaza — with questions over what, if any, role Palestinians will play — makes many observers nervous.

“The construct is pseudo colonial; all of these outside powers are somehow creating a new protectorate,” said Hanna at the International Crisis Group. “So it’s very strange and it’s really not clear how that’s going to work.”

Hellyer likened Blair’s proposed role to that of the viceroys used by empires such as Britain to oversee India and other colonies.

“People who are not connected to Gaza or the West Bank or Palestine at all are going to be governing Gaza with very minimal Palestinian involvement,” he said. “So Blair or no Blair, I think that that’s going to be something that will be difficult to politically justify.”