Copyright scmp

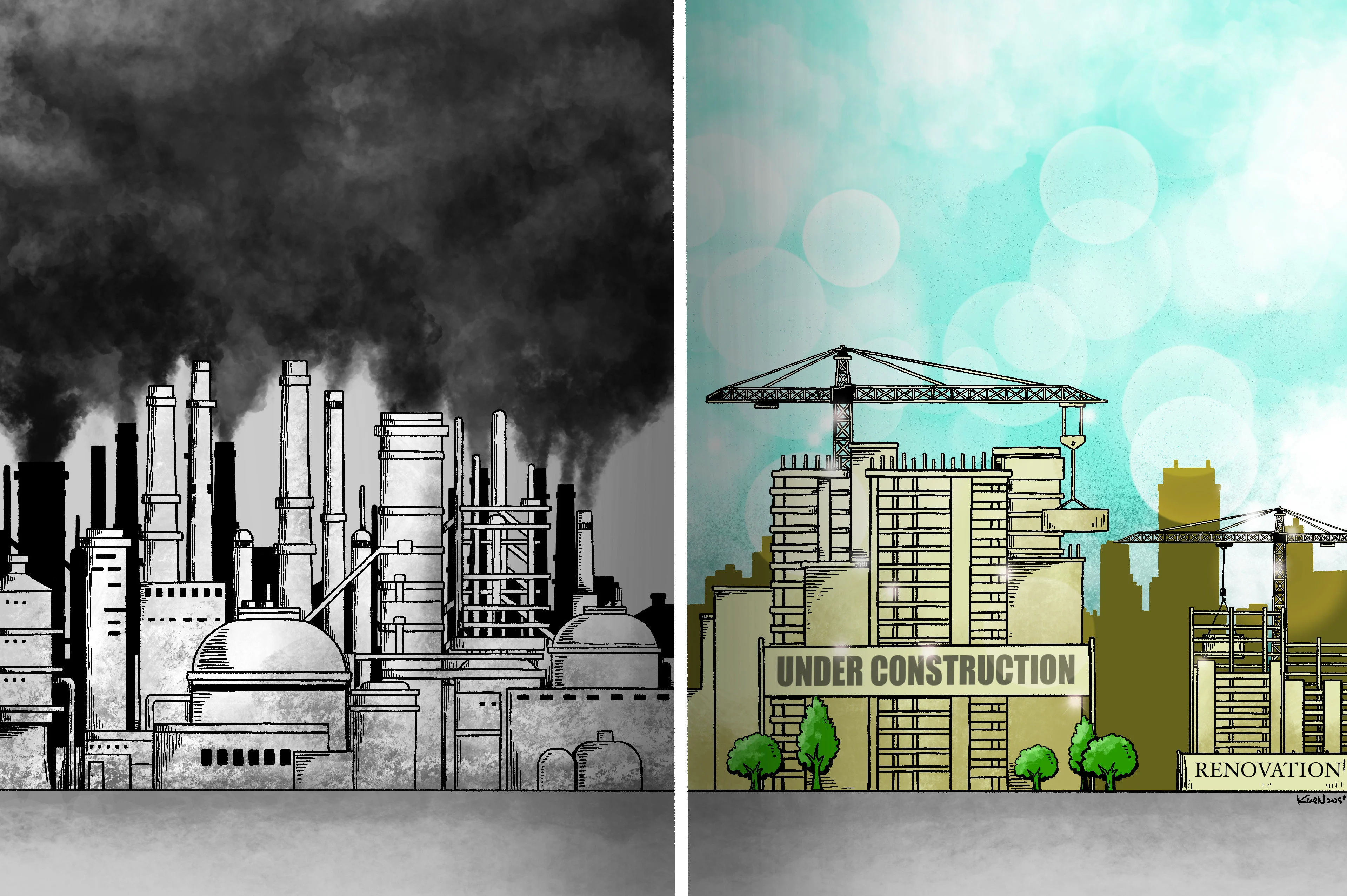

Few areas of China reflect the country’s decades-long economic transformation more vividly than its cities. Rapid development has made villages into dense urban landscapes and already sizeable metro areas into some of the world’s largest population centres. As the rate of urbanisation slows and the country transitions into a new economic era, we explore how select Chinese cities are navigating the change. Read the rest of our series here. Once a remote industrial powerhouse forged deep in the mountains of western China, the former “steel capital” Panzihua is trading blast furnaces for wellness resorts as it pushes to align with the nation’s shift from rapid urbanisation to a more “people-centred” model. Built in the 1960s on the upper reaches of the Yangtze River, the city in Sichuan province drew workers from across the nation to fuel China’s industrial ambitions. Six decades later, its economy, once mirroring Pittsburgh’s in the United States, still relies on the iron ore buried in its hills – home to Pangang Group, western China’s largest steel enterprise – even as it pursues a cleaner, more diversified future. Today, Panzhihua has a population of about 1.2 million, a broader range of industries and a greener environment. Named after a type of kapok flower, the city is working to avoid a “rust belt”-style decline – though the transition is not without challenges. According to researchers and local residents, it continues to grapple with a narrow industrial base, limited innovation capacity and difficulties attracting talent. Hundreds of resource-dependent cities like Panzhihua emerged during an era when urban planning centred on the needs of heavy industry. But as the world’s second-largest economy undergoes a structural transformation, many have been forced to rethink their strategies. “China’s many resource-dependent cities – whether reliant on coal, oil, steel or non-ferrous metals – were key tools of productivity in the planned economy era. But after decades of development, many face the dilemma of resource depletion,” said Song Yingchang, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. “Panzhihua is a microcosm of China’s urbanisation shift, from ‘industry-driven city-building’ to ‘people-centred’ development,” he added, while cautioning that so far, few cities attempting this transition have achieved complete success. From smoky skies to sunshine West of Panzhihua’s urban centre along the Jinsha River, abandoned cement plants, power plants and railways serve as stark reminders of the city’s industrial past. Old Panzhihua was an ‘industrial powerhouse’ choked by coal, steel and vanadium-titanium factories. Locals like us all had rhinitis, with constant sneezing in dusty seasons Chen Han, hotel worker In 1965, Panzhihua was chosen to host southwest China’s major steel plant because of its rich iron ore reserves, part of Chairman Mao Zedong’s “Third Front Construction” campaign to shift defence and industry inland. Today, some of these derelict sites have found new life. In Gaojiaping in the city’s west, a former cement plant has been repurposed into a film base and tourist attraction, generating new sources of revenue. Downriver to the east, the contrast is even more striking. Hillsides now host a wellness resort filled with villas, flats and greenery, home to fitness clubs, bike paths, parks, leisure centres and hospitals. The trend highlights Panzhihua’s push to diversify. Blessed with mild winters and abundant sunshine, the city attracts older visitors from Sichuan and beyond for seasonal stays – a testament to its long-term efforts to reinvent itself. “To me, the biggest change in the city is the air quality and climate,” said Chen Han, a hotel worker in her late twenties. “Old Panzhihua was an ‘industrial powerhouse’ choked by coal, steel and vanadium-titanium factories. Locals like us all had rhinitis, with constant sneezing in dusty seasons.” The closure of highly polluting plants over the past decade has cleared the air, easing living conditions for most people, she added. In Ashuda village in the east, Bao Hua works at a homestay owned by the village collective, next to what was once a “huge black lake” – a 123-million-cubic-metre (4.34 billion cubic feet) tailings dump from Pangang Group. The government relocated villagers a decade ago and transformed the site into a park, spurring new income opportunities through tourism and the wellness sector. Bao now earns a fixed monthly salary of over 2,700 yuan (US$379). “Before the development, we farmed mangoes or rice and raised livestock – there was little income. Now I work while tending to my family’s mangoes. It’s much better than before.” Panzhihua’s residents earned an average disposable income of 41,780 yuan last year, or about 3,400 yuan per month, according to official data. Bao noted that the tourist season generally runs from November to March, with business slowing for the rest of the year. But for Lei Xiaopeng, a local who ran a travel agency before the coronavirus pandemic, the city’s transformation remains a work in progress. “It still lacks truly attractive tourism resources. Sites like the Gaojiaping industrial heritage base mainly cater to local students and government agencies for patriotic education, so the audience is narrow,” he said. While the Jinsha River borders the city, its waters are too turbulent for recreation. A drifting festival in the early 2000s was discontinued for safety reasons, he added. Wellness tourism has brought some vitality, but not enough to sustain the local economy, while efforts to rebrand Panzhihua as a “fruit city” have failed to supplant traditional industries, according to Lei. Chen, the hotel worker, helps her parents sell the mangoes, pomegranates and avocados they farm in the suburbs on social media. “The government is building a fruit production brand, but agriculture in China is mostly the same. It’s not a profitable industry. For me, it’s just a side gig – it can’t become one of the city’s pillar industries,” she said. Young people like Chen face limited job opportunities and few specialist roles with growth prospects, she said. “On the other hand, transport options to nearby cities or out of the province are limited, lacking the convenience and vibrancy of big cities, making it hard to retain ambitious young people.” To this day, Panzhihua’s pillar industries stem from its mineral resources: steel, and vanadium and titanium, two metals found in local iron ore. Together, they account for over 70 per cent of the city’s gross domestic product, according to figures from the municipal government. Vanadium is widely used in steelmaking, chemicals, aerospace and other fields for its structural integrity, while titanium – known as “space metal” or “strategic metal” – is prized in hi-tech industries. With China’s steel sector facing chronic overcapacity for the past two decades, Panzhihua has shifted its focus to investing in cleaner, more efficient technologies, positioning the vanadium and titanium sectors as drivers of innovation. In 2023, these metals surpassed steel for the first time in output value: 52.1 billion yuan (about US$7.3 billion) compared with 43.2 billion yuan for steel, according to municipal government data. Still, challenges persist. Most local enterprises suffer from severe product homogenisation, limited innovation and a lack of competitive high-end products, according to a study published in the Chinese journal Iron Steel Vanadium Titanium in December 2023. Researchers noted that the steel industry also accounts for about 90 per cent of the city’s vanadium consumption, while high-value added applications remain in urgent need of expansion. The road ahead There are 262 resource-dependent cities like Panzhihua across China, accounting for about 40 per cent of the country’s total and one-third of the population, according to a State Council plan on their sustainable development for 2013-2020. China later issued a plan dedicated to these cities and other resource-dependent areas, calling for action to ensure faster economic transformation, greener, more liveable environments and improved livelihoods from 2021 to 2025. The plan aligns with China’s evolving strategy on urban development. At the Central Urban Work Conference in July, policymakers emphasised the shift from rapid urbanisation to stable, efficient and high-quality development. The new goal is to build “innovative, liveable, beautiful, resilient, civilised and smart modern people’s cities”, according to a readout of the meeting from state news agency Xinhua. Official data shows that China accomplished in just a few decades what Western developed nations took more than a century to achieve. By the end of 2024, 67 per cent of the population – about 940 million people – were working and living in cities. For mid-western cities like Panzhihua, treat them as mining areas, not as cities to develop. Administrative levels should be low, county-level at most Song Yingchang, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Cities like Panzhihua – long reliant on the mining sector – tend to have a narrow industrial base and weak supporting industries, making it challenging to create enough jobs to attract talent, Song of CASS said. “Moreover, these enterprises were initially situated in remote areas, deep in mountains and forests. Cities built around them inherently have shortcomings, with isolated and hard to form synergies and an effective division of labour with neighbouring cities,” he said. By contrast, resource-dependent cities in eastern provinces – such as Tangshan in Hebei and Xuzhou in Jiangsu – have had smoother transitions and are among the few relatively successful cases, he added. Looking to the US, Houston in Texas and Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania could offer some lessons, he said. Houston transformed from a resource-dependent oil boomtown into a diversified economic powerhouse by leveraging its energy sector’s expertise to expand into healthcare and advanced manufacturing, while Pittsburgh transitioned from a declining steel capital into a tech and innovation hub through aggressive reinvestment in universities like Carnegie Mellon, fostering robotics, biotech and autonomous vehicles. “But such transformations in China may require higher-level nurturing, selecting a few cities carefully – it’s impossible to have 100 Houstons,” Song said. He cautioned that industrial shrinkage is inevitable as natural resources are exhausted. “For mid-western cities like Panzhihua, treat them as mining areas, not as cities to develop. Administrative levels should be low, county-level at most, and they shouldn’t bear the task of being regional economic centres.” A Chinese county is on the third tier of the country’s hierarchical governance structure – below provinces and prefecture-level cities. Panzhihua, whose GDP grew by 60 per cent from 2014 to 2024, is currently a second-tier prefecture-level city. For Lei, the former tourism industry worker, the biggest obstacle to the city’s future vitality is its inability to attract young people. His son, who is studying at a university in the provincial capital Chengdu, has clearly stated that he will not return home after graduation. “He says there are too few opportunities here,” the father said.