The Atlantic hurricane season is waking up after one of the longest lulls in tropical storm activity in recorded history.

For the first time since 1939, there wasn’t an active tropical storm or hurricane in the Atlantic basin between Aug. 28 and the peak of hurricane season, Sept. 10.

August usually produces four named storms, while September produces around five if we look at all seasons since 1966, when the satellite era began. This year, we’ve seen a total of four tropical systems over both months, though this will likely change as two tropical disturbances have a chance to build into a tropical storm or something stronger by the end of the month.

Advertisement

Still, this lull can’t be dismissed, because over the past 10 years, August and September have actually produced 1 to 2 more named storms because of warming seas.

So what’s behind the anomaly of a quiet Atlantic during such a historically active stretch? Let’s break it down.

Strong wind shear

Wind shear is not good for hurricane formation. Shear means different wind speeds and directions as you rise higher into the atmosphere. Tropical systems need to be able to tap into the fuel source of warm seas in order to form a cluster of showers and thunderstorms. If there’s strong wind shear aloft, these winds rip apart the convection necessary for storms to stay organized.

During this epic lull, wind shear was strong and limited the growth of tropical waves, clusters of energy, pushing from the west coast of Africa into the Main Development Region (MDR) west of the Cape Verde Islands. The subtropical ridge, better known as the Bermuda High, was particularly strong at the end of August and beginning of September.

Advertisement

Saharan dust was above average

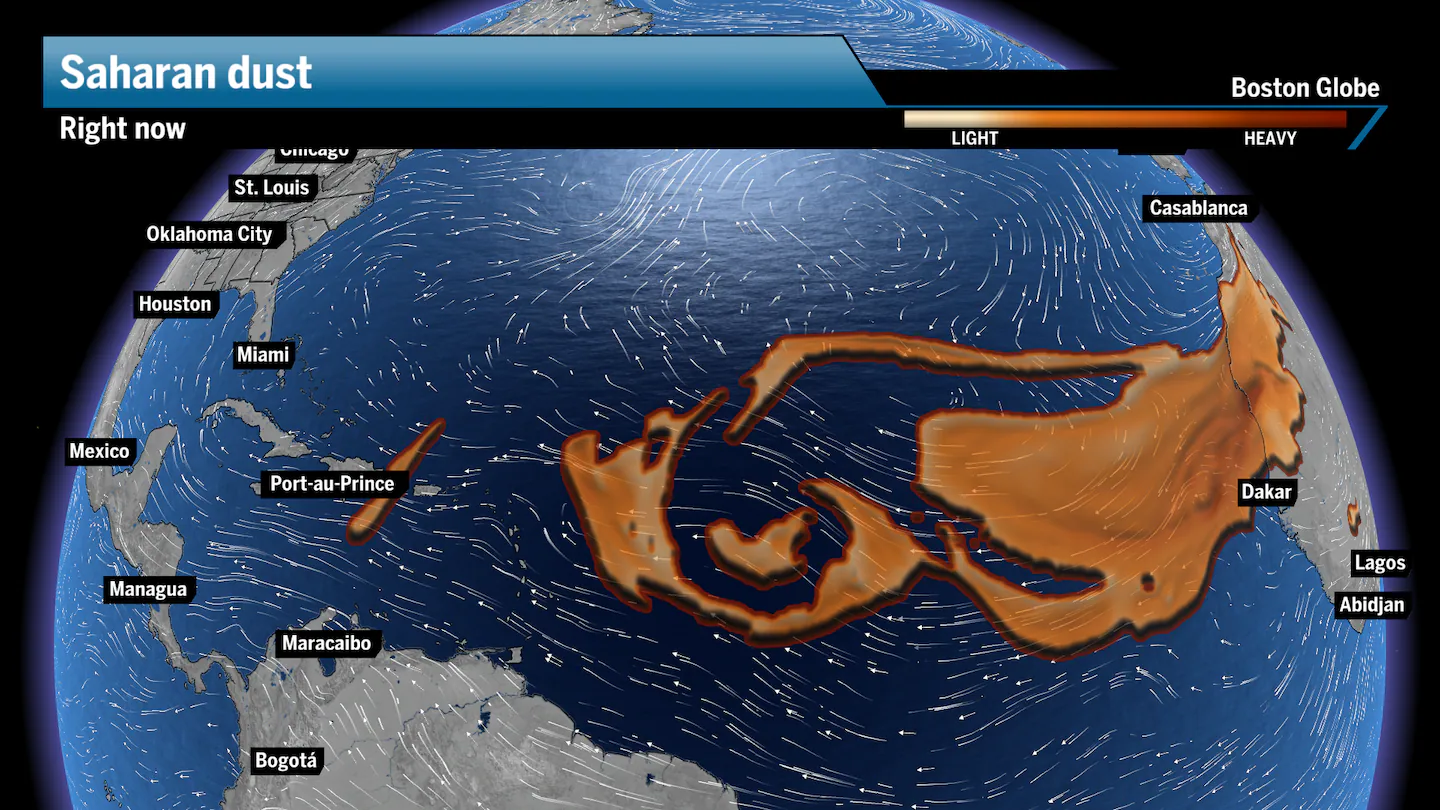

Each summer and fall, the trade winds push west through Africa and pick up plenty of dust, carrying particles thousands of miles throughout the Atlantic Ocean.

During this extraordinary lull of tropical activity, Saharan dust was present in the atmosphere, often in above-average amounts. These plumes hold very dry air, reducing available moisture for storm formation. The dust also blocks out some of the heat from the sun and may cause brief reductions in sea surface temperatures, which we saw in the eastern and central zones of the MDR.

We typically see the Saharan dust layer calm down during the second half of September, but we still see a decent amount over the MDR. But both disturbances currently in the Atlantic are on the eastern edge of the dust, and should be able to develop before the dust arrives.

The Madden-Julian Oscillation

The Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) is a naturally occurring phenomenon where pockets of high and low pressure travel east across the equator, circling the globe. When low pressure is present, rising air holding moisture from the ocean can produce thunderstorms and, thus, tropical activity. If high pressure is present, then sinking air will suppress storm development.

During this stretch, the MJO was in a negative phase over the Atlantic, meaning high pressure was present with sinking air, making it difficult for storms to form.

Typically, the MJO cycle will deliver periods of high or low pressure every two weeks or so across the Atlantic. We saw a positive MJO when Hurricane Erin erupted, and the same with Gabrielle.

Advertisement

Right now, the phase is about neutral, which means it’s a coin flip as to what will unfold with the two disturbances in the Atlantic. We think ultimately two named storms will come out of these disturbances, with the western disturbance likely weaker than the eastern one.

Ken Mahan can be reached at ken.mahan@globe.com. Follow him on Instagram @kenmahantheweatherman.