Copyright Anchorage Daily News

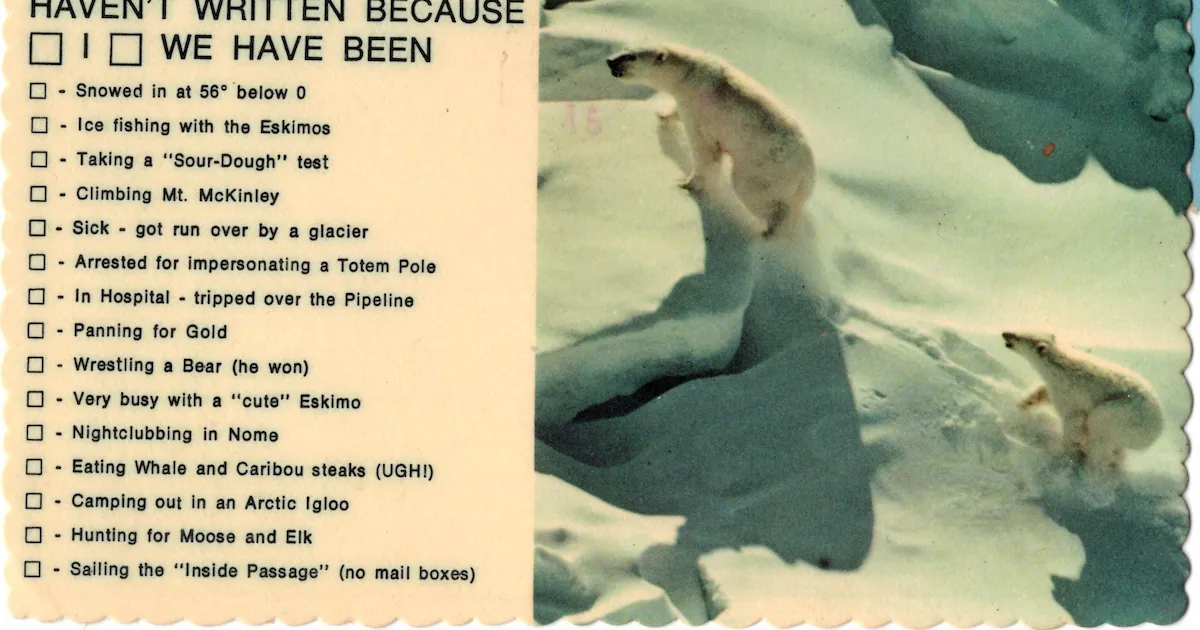

Part of a continuing weekly series on Alaska history by local historian David Reamer. Have a question about Anchorage or Alaska history or an idea for a future article? Go to the form at the bottom of this story. People sometimes ask me, “What sort of sources do you use in your research?” And the honest answer is: everything. All the products and detritus of the natural world and human culture are fair game, such as they are available. Newspapers, books, reports, journal articles, theses, oral histories, photographs and objects of every type all make for crucial source materials in varying contexts. In this column alone, there have been articles about phone books, board games, tokens and bullet pencils. Then there are postcards, including the comments about Alaska left on them. If you are reading this column, it is reasonable to assume you have some curiosity about history and a more than passing fascination with this place called Alaska. Yes, it is contagious. No, it is not fatal or otherwise deleterious to your health, but it can sometimes be expensive. Many people with these interests soothe their desire for Alaska history by collecting Alaskana, which can be costly depending on the types of objects they prefer. Art and rare books can leave a real dent in the checking account, or so the humble historian has been told but not experienced because he is a humble historian. In the main, postcards are affordable, easily stored, readily available, and devoted to nearly every historical topic of interest. Do you like steamships? Well, there are postcards galore on them, frequently capturing rare images. Are you more interested in the gold rushes? People have always loved gold rush lore, so there are plenty to choose from. Buildings, notable people, aerial photography, humor: it is nigh impossible to run out of options. But postcards are also historical documents. In some instances, postcards of famous views or photographs are easier to obtain or access than the originals. In some instances, postcards are the only surviving documentation, particularly within certain timeframes and of objects, people or buildings that no longer exist. And while most postcard collectors prefer pristine copies, there are lessons and entertainment that can be gleaned from used versions. This postcard captures one of the most popular images of Alaska from the 1910s, the wreck of the Princess May. On Aug. 5, 1910, the steamship was churning through the Lynn Canal en route to Vancouver when it ran aground upon a reef by Sentinel Island, near Juneau. The ship was left jutting at a 23-degree angle out over the water, a striking image captured on numerous postcards. The steamer remained on the rocks for nearly a month, more than enough time for every camera-owner person around to sail out for the view. Juneau-based photographer William H. Case (1868-1920) took this famous image. Born in Iowa, he made his way north as a prospector in 1898 before opening a photography studio in Skagway. As Skagway declined from its gold rush peak, Case relocated to Juneau, where he lived for the rest of his life. This copy was mailed in 1917 to a woman in Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada. The sender wrote, “Had a dandy trip up here. Lovely weather on the Boat. Nice weather here raining most of time.” It was also sent from Hadley, a short-lived mining town on the Kasaan Peninsula northeast of Ketchikan. It had its own post office from 1912 to 1918. Joe McGinniss offered a similar, if dourer, take on Southeast Alaska weather in his 1980 travelogue, “Going to Extremes.” About Juneau, he wrote, “Oh, such rain. It fell day after day, week after week, month after month. Sometimes sleet, sometimes snow, but, in the end, rain again. Soaking through clothes, through the skin, into the soul. Young men stumbled groggily from one bar to another ... This was the only state capital in America where you needed a topographical map, as well as a street map, in order to find your way around.” St. Michael (Taciq in Central Yup’ik) is a village on St. Michael Island, southeast of Nome and southwest of Unalakleet. During the Klondike Gold Rush, St. Michael was a crucial waypoint on the water route to the gold fields. Those prospectors with the necessary bankroll could sail from the West Coast to St. Michael, where they would board smaller boats that would travel up the Yukon River. This path was both safer and far more expensive than the alternatives, either crossing through the Alaska Panhandle or traversing Canada. Most geographically specific postcards used for their intended purpose are mailed by newcomers or visitors, especially before the rise of small, affordable cameras. In 1920, a woman named Geneva mailed this postcard to a man in Clinton, Wisconsin. She noted, “Arrived Aug 6, and as water is scarce up here, I took a hasty dip in Bering Sea. Once was enough. It’s not like Delaware.” No, Alaska is indeed not like Delaware in nearly every way. Dogs are, of course, a common subject of Alaska postcards. Few are cuter than this circa 1900 to 1909 postcard of “Bob,” a most handsome and well-behaved exemplar. This particular copy was mailed in 1909 to a gentleman in Providence, Rhode Island. The sender pithily noted, “This beats Mexico.” Frank H. Nowell (1864-1950) captured this image, almost certainly around Nome. In 1900, he opened a store in nearby Teller, though he soon spent more time traveling around the Seward Peninsula, taking photographs of nearly everything. At first an amateur pursuit, he was a professional well before the decade was out. By 1908, he was also spending most of his time in Seattle, more so after he was selected as the official photographer of the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. He advertised his studio as possessing “a photograph of everything in the great North but the pole itself.” In 1922, Ralph Pederson mailed this postcard of Seward, likely acquired upon arrival in that city, to a woman in Westport, Oregon. Pederson was “Way up in Alaska going to work for the govt. Rail Road.” And then he declared, “Here we have the best climate in the world.” As he notes, he left Seattle on May 27th. His message is dated June 3. While he was kind to speak so well of conditions in the North, he knew not what would come. In an Aug. 12, 1869 speech in Sitka, former Secretary of State William Seward more accurately described the weather in Alaska. He stated, “The weather of this one broad climate of Alaska is severely criticized in outside circles for being too wet and too cold. Nevertheless, it must be a fastidious person who complains of climates in which, while the eagle delights to soar, the hummingbird does not disdain to flutter.” He added, “It is an honest climate, for it makes no pretensions to constancy.” This postcard exists as evidence that some Alaska jokes are eternal. A bearded man holds aloft his latest hunting trophy, a massive mosquito that was skillfully inserted into the original photograph. The back notes: “An Alaskan Mosquito Shot in the Spring Thaw of 1967.” This copy was mailed from Fairbanks to St. Charles, Illinois in 1968. The sender noted, “Hap made a mistake for not bring his saddle along, they are big enough to ride.” He added, “But we sure having fun so far, going fly to arctic tomorrow. They give you warm close [sic] if not we would freeze. See things I never of dream of see. Today we were at the North Pole.” In 1869, C. P. Raymond of the U.S. Army Engineer Corps led the first official American reconnaissance of Alaska. Perhaps more than anything else, Raymond discovered massive swarms of mosquitoes and gnats. He wrote, “We were obliged to wear face nets and gloves, and on occasion an attempt to make sextant observations failed completely.” In other words, the mosquitoes were so dense that his company could occasionally not even read their instruments. Horrifying. For many years, the electronic temperature and time sign outside the First National Bank building at the corner of Second Avenue (Two Street) and Cushman Street was one of the more photographed locations in Fairbanks. Before the sign outside the University of Alaska Fairbanks, this was the best way to document the extremes of local weather. Installed in 1952, this sign initially ran hot because its sensor was initially placed near a steam vent. And so, on July 30, 1973, Lois Pore mailed this postcard to the Joe Funk family in Atlanta, Georgia. “This is a cool thought if it is hot in Georgia. Fairbanks was about 75 degrees when we were there July 23rd.” The images of freezing winters taunted the poor tourist who was instead enduring a regular Fairbanks summer. Pore added, “The U.S.A.(‘s) 49th state is most interesting.” Woof, woof, mush Woof, woof, mush Woof, woof, mush, mush, mush Woof, woof, woof, woof, woof, woof, woof Mush, mush, mush, mush, mush. As noted by the author, this is, of course, the “Alaska State Song,” sung to the tune of Jingle Bells, no matter that it does not quite work. The intent, at least, is obvious, and readers have likely met some overly credulous Outside individual who would believe that this is the state song. The unnamed sender continued, “Yes, this is really from Alaska. Yes, they have many dogs here (woof).” Most vintage postcards lack a copyright date or explicit indications of when they were printed. This is an obvious design feature as postcards are meant to be shelf-stable items, built for possibly extended shelf residencies. Customers tend to react differently when they know how long a product has been collecting dust on a shelf. Without a date, all postcards seem new to the tourist. However, this lack of information negatively affects collectors and historians, who are more interested in the postcard’s context than its postal utility. This postcard, while lacking a date, was produced by Dexter Press and includes their internal inventory number on the back, in the lower left. The “38444-D” notation indicates it was printed sometime from 1975 to 1983, even though it was not mailed until 1995. From dogs to weather, each of these visitors experienced familiar Alaska moments. These postcards — these images of Alaska — were how they chose to memorialize their travels. As for postcards in general, if enough people are interested, I will write more on the tricks and tips for collecting them. Fill out my Wufoo form! Key sources: Allmen, Diane. “Dating Dexter Press Postcards.” Postcard History. October 7, 2021. Frank H. Nowell studio advertisement. Official Program of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. Seattle: 1909, 92. Gjullin, C.M., R.I. Sailer, Alan Stone, and B.V. Travis. The Mosquitoes of Alaska, Agriculture Handbook No. 182. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture, 1961. McGinniss, Joe. Going to Extremes. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980. Seward, William H. Alaska Speech of William H. Seward at Sitka, August 12, 1869. Washington, D.C.: James J. Chapman, 1879. Turner, Robert D. The Pacific Princesses: An Illustrated History of Canadian Pacific Railway’s Princess Fleet on the Northwest Coast. Victoria, British Columbia: Sono Nis Press, 1977.