Like most people, I had my first encounter with Robert Redford through a movie screen.

When I was 9, I took a city bus from the edge of Spokane, Washington, into downtown — to the Fox Theater, then a somewhat beaten-down old movie palace that had converted its balcony into two extra screening rooms. In one of those smaller rooms, in the spring of 1974, I went to see the movie that had just won the Best Picture Oscar: “The Sting.”

Twenty years later, as The Salt Lake Tribune’s movie critic, I had my first extensive interview with Redford, when his movie “Quiz Show” had just hit theaters. Toward the end of the interview, I told him about the adventure the 9-year-old me had, seeing him in the first movie for grown-ups that I ever saw alone. Redford didn’t say anything in response, though he left me with the impression that he wasn’t thrilled at being confronted by the 28-year age gap between us.

That moment was a small hiccup in an otherwise congenial interview — the first of many times I talked with Redford in the 30-plus years I’ve covered him, his Sundance Institute and the Sundance Film Festival for The Tribune.

Since Redford’s death Tuesday at age 89, in his sleep in his Provo Canyon cabin, I’ve been asked about my encounters with “the Sundance Kid” — and what I learned about him, his connection to Utah, and his effect on film and the world.

I learned a lot from Redford from my earliest interviews in 1994. For starters, one was to address him as “Bob.”

What about Bob?

In the waiting room of Redford’s office, I nervously practiced in my mind how I would greet him. I ran through the words, “Hello, Bob,” over and over — but it felt forced, like I was trying too hard to be casual. But the second Bob walked in, he offered his hand, I shook it and said “Hi, Bob,” like it was completely natural.

That was Robert Redford’s superpower: The uncanny ability to put people at ease.

By this point, at 57, Redford was good at being Robert Redford. He knew the effect his presence — his charisma, his good looks, those blue eyes — had on people, and he was adept at using those traits to disarm folks. He helped people, like me, get past the “Oh my God, I’m talking to Robert Freaking Redford” of the moment and get down to business.

My editor then, who held the role as The Tribune’s movie critic before I did, gave me an important interviewing tip for Redford: “You’ll ask your first question, and 10 minutes later, you’ll ask your second question.”

Redford could hold the floor better than any filibustering politician. But he didn’t ramble. He had a lot of thoughts, a lot of powerful ideas, and he wanted to be sure you understood exactly what he was thinking — about Hollywood, film, storytelling, current politics, you name it.

He also knew that a lot of journalists around my age were influenced, one way or another, by his fictional portrayal of a real journalist, Bob Woodward, in the 1976 drama “All the President’s Men.” He was of two minds about that, I think, because not all of those journalists aspired to Woodward’s level of ethical rigor.

‘Redford Standard Time’

Another revelation from those early interviews, which I also encountered with him later, was Redford’s flexible relationship with time. If one had an appointment with Bob, he may arrive on time, or he might not. People at Sundance coined the term “Redford Standard Time.”

In the waiting room at his office cabin for that first full interview, I saw his assistant pull out a container of peanut butter oatmeal cookies from the Sundance resort’s restaurant. She called them “waiting-for-Bob” cookies. Bob arrived on time for that interview, so I barely got two bites.

In January 2000. I was covering a festival reception in Park City, and Redford was in attendance to call attention to documentary filmmaking, one of his passions. My wife, Leslie, came up to visit while I was working, and brought our then-4-month-old son, Alex (who’s turning 26 this week).

Leslie and Alex were relaxing on a couch in the back of the room, while I was interviewing Bob and others. At one point, a Sundance publicist found Leslie, and said, “Bob wants to meet the baby.” We have a photo of baby Alex wrapping his tiny hand around Redford’s pinky.

Here’s the postscript: When Alex’s hair grew in, it was blond — not a color he inherited from us. It stayed blond for several years.

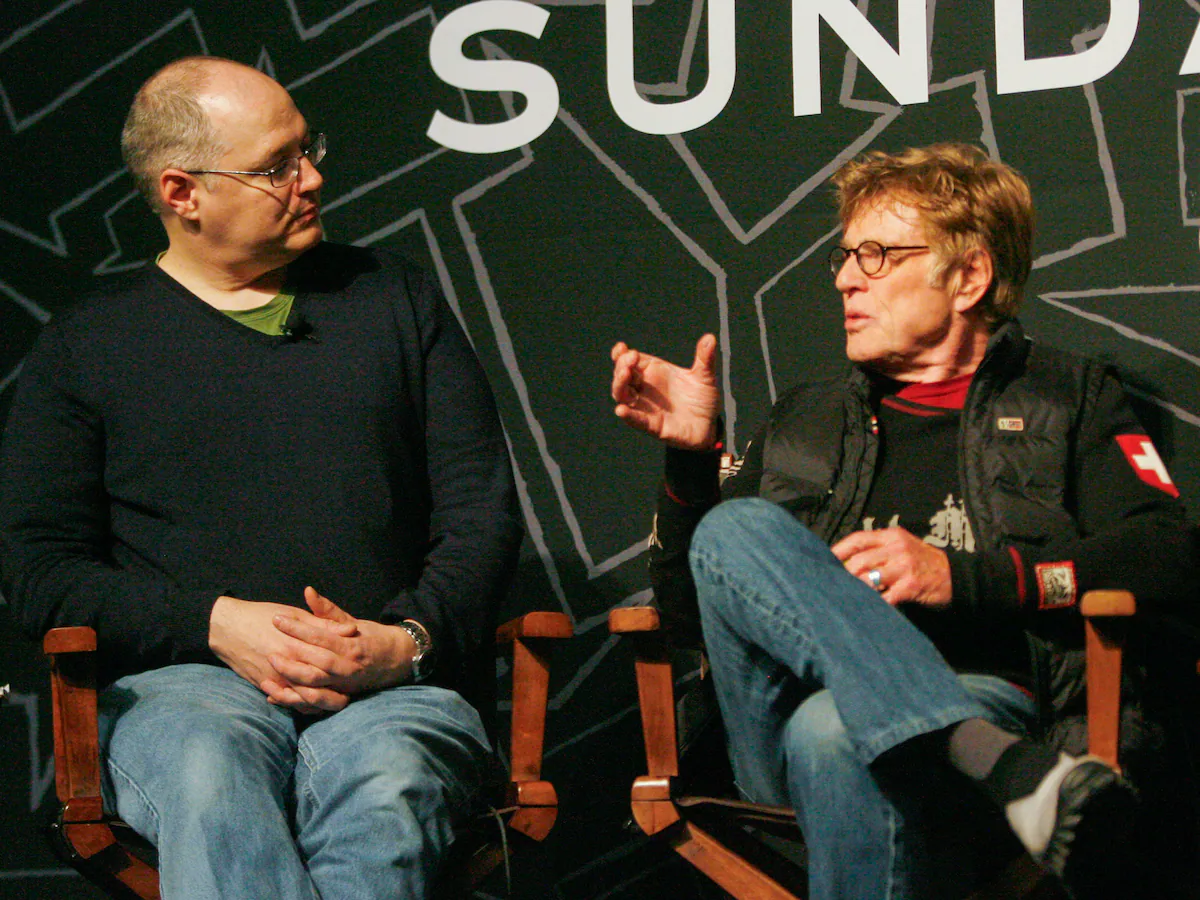

Another strong memory is from the 2014 festival. For four years, Sundance invited me to moderate the opening-day news conference at Park City’s Egyptian Theatre. This was a chance for reporters from around the world to ask questions of Redford and Sundance officials about the festival and the institute’s mission.

The news conference was not Redford’s favorite chore. In 2019, shortly after he retired from acting, Redford put in only a cameo appearance at the news conference, saying, “I don’t think the festival needs a whole lot of introduction now.” In 2020, he didn’t take part in the news conference at all.

The 2014 Oscar snub

The 2014 news conference happened the same morning the Academy Award nominations were announced — and the industry and movie fans were stunned that Redford wasn’t nominated for his performance in the one-man survival drama “All Is Lost.”

The question reporters wondered before the news conference was: Would Redford talk about the Oscars? My question was: Should I be the one to ask him?

My thought was that somebody was going to ask, so it might as well be me — acknowledge the elephant in the room early, let Redford say his piece, and move on to talking about the festival.

In the green room before the event, I was brought in to talk to Bob. His message to me (I’m paraphrasing) was that I was a journalist, and I should ask the questions I would normally ask. Onstage, I asked. He told a joke. Then he answered seriously that “Hollywood is what it is, and it’s a business,” and the lack of a sustained Oscar campaign likely hurt the movie’s chances.

“I was so happy to do this film, because it was independent — that’s what’s on my mind,” Redford told me on the Egyptian stage. “The rest is not my business; it’s somebody else’s business. I’m fine.” Hollywood trade papers were publishing Redford’s quote before we got off the stage.

His love for Utah

Redford also spoke at that news conference about his enduring connection to Utah.

“The state and I might have differences, political differences or otherwise — but it’s a great state, a beautiful state,” Redford said. “I came here because of the beauty. I came here because of the state’s particular history, the pioneer history. I wanted to preserve that at Sundance, but also I wanted to add something that would create a new dimension. So I said, ‘Let’s make this festival. … Let’s take it to Utah, put it in the winter, make it weird.’”

The last time I saw Redford in person was in August 2022 at the Sundance Mountain Resort. He had sold the resort two years earlier, and was there with about 100 people to dedicate 316 acres of the resort’s land — filled with aspen trees and wildflowers — to create a nature preserve.

He looked frail, as a man nearing his 86th birthday might. His daughter Amy helped him as he walked from an SUV to a chair under the shade for the ceremony — which included speeches, a prayer from a Ute tribe spiritual leader and three Utah Symphony musicians playing Dvorak. I still have the cup from the champagne toast.

Bob’s voice was as resonant as ever. He read a letter from his son Jamie, who had died less than two years before, which expressed the family’s concern about being “good stewards of the natural world.” I don’t think I saw one person who wasn’t brushing back a tear.

In the days after Robert Redford’s death, many people have shared their memories of the man, and his effect on movies, environmental activism, Utah, the nation and the world. Telling our stories is a fitting tribute, because Bob was all about storytelling and making sure everyone’s story could be shared.