By Karen Tei,Samuel Mbura 34am

Copyright myjoyonline

In the UK, a driving licence is not a luxury but a necessity, just like in other advanced countries, integral to employment and daily life. While the economy facilitates easy car ownership through credit, the system is deliberately designed to prioritise safety over convenience.

One must first obtain a license, a process that involves rigorous theoretical and practical examinations, before owning a car. Many people have even given up after failing several times!.

This process comes at a significant cost, with individuals often investing between £1,000 and £2,000 or more in professional lessons. Despite the high demand and considerable backlogs for tests, the standards remain non-negotiable.

Notably, international driving experience is not recognised; every new resident is classified as a learner and must master the UK’s specific rules of the road. Mind you, the steer is to the right!.

The system’s robustness is underpinned by technology and stringent enforcement. Driving without a valid licence, insurance, or MOT (roadworthiness certificate) carries severe legal consequences that can affect one’s permanent record.

Even with a licence, it is treated as a privilege that can be revoked for flouting regulations. In fact, holding a UK driving license is a prestige!. Let me add that it doesn’t matter your status, “The law is law” and applicable to everyone equally without interference from “above”!.

These comprehensive measures have contributed significantly to reducing traffic accidents and dangerous driving, earning the UK a reputation as one of the world’s safest countries to drive in, with a remarkably low rate of 2.4 road traffic deaths per 100,000 people (WHO, 2025). This success is built on:

Protection for vulnerable road users: Pedestrians, cyclists, and motorcyclists.

Quality infrastructure: Well-maintained roads without potholes.

Strict vehicle safety standards.

Technology-led enforcement of traffic laws.

While acknowledging the developmental gap between the UK and Ghana, the strategic principles are transferable. My focus on this issue is personal and professional, having spearheaded the #DriveSafe campaign on JoyNews, which used documentaries and stakeholder engagements to raise awareness about the carnage on our roads.

Although the 2025 WHO report may not list Ghana among the very worst, the domestic reality is alarming. The latest figures from the National Road Safety Authority (NRSA) reveal a deeply concerning 21.6% surge in fatalities for the first half of 2025, with 1,504 lives lost, averaging approximately 8 deaths per day.The contributing factors are well-known:

Human Error: Reckless overtaking, speeding, driver fatigue, and alcohol impairment.

2. Poor Road Infrastructure: Inadequate lighting, faded lane markings, potholes, and unfinished roadworks.

3. Lack of Enforcement: Insufficient traffic law enforcement and corruption.

Agencies like the MTTD, NRSA, and DVLA, often with partners, have initiated awareness campaigns. A key technological step was the 2023 launch of “Traffitech-GH,” which I reported on (https://www.myjoyonline.com/ghana-police-service-launches-traffitech-gh-to-detect-road-traffic-offenses/), designed to automatically detect and bill traffic offenders like systems in the UK. Yet, the situation deteriorates.

Our infrastructure enables casualties, but the core issue is driver literacy. Many drivers are unqualified, unlicensed, uninsured, or operating unroadworthy vehicles. The resistance to full digitalization, which would minimize corrupting human contact, hinders progress.

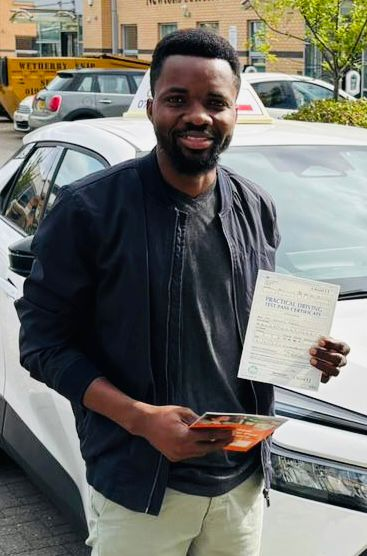

From personal experience, holding a valid international driving permit, the UK system made no exceptions. I was required to learn every road sign, roundabout rule, and regulation. This investment in learning was crucial to passing on my first attempt. The insurance alone for international license holders is a disincentive! You’re likely to pay not less than £200 per month, depending on the crime rate in your area!.

Furthermore, road safety is treated as a collective responsibility in the UK; citizens routinely report bad driving, and thanks to a synchronized national database, offenders are swiftly traced and penalised.

This contrasts sharply with Ghana, where reporting bad driving is rare and enforcement is inconsistent, lacking the deterrent effect of certain punishment. In the UK, offences lead to fines, penalty points on the licence, or outright bans.

Therefore, tackling Ghana’s road carnage must begin with a foundational emphasis on education. Introducing compulsory road safety courses from basic school, perhaps, would instill awareness and respect for regulations in future generations. In the UK, even a child understands their rights and can report dangerous driving.

This is where I believe the long-term, transformative potential of the Free SHS policy must be recognized. Its impact extends beyond the classroom, as it is a critical investment in national literacy. Imagine a Ghana in ten years where the average young person is at least a high school leaver. This demographic would be equipped to read, write, and comprehend road safety regulations.

Since human error stemming from road illiteracy is a primary cause of accidents, a more literate population of future drivers and pedestrians is a fundamental prerequisite for safer roads. Even the best infrastructure will fail without literate road users.

Concurrently, regulatory bodies must act decisively. The DVLA, MTTD, NRSA, and insurance companies must tighten requirements to eliminate unlicensed and unqualified drivers. A stringent policy shift would be for insurance companies to insure drivers, not just cars.

This would prevent unlicensed individuals from driving vehicles that do not belong to them. Specifically, an insurance policy’s rate can also be based on location according to the crime rate, as is done in the UK.

Finally, the Traffitech technology launched in 2023 must be fully operationalized across major roads to automatically fine and prosecute offenders via a centralized, synchronized database.

By combining long-term educational investment (through policies like Free SHS) with stringent, technology-driven enforcement today, Ghana can build a safer road culture for future generations.