Copyright Project Syndicate

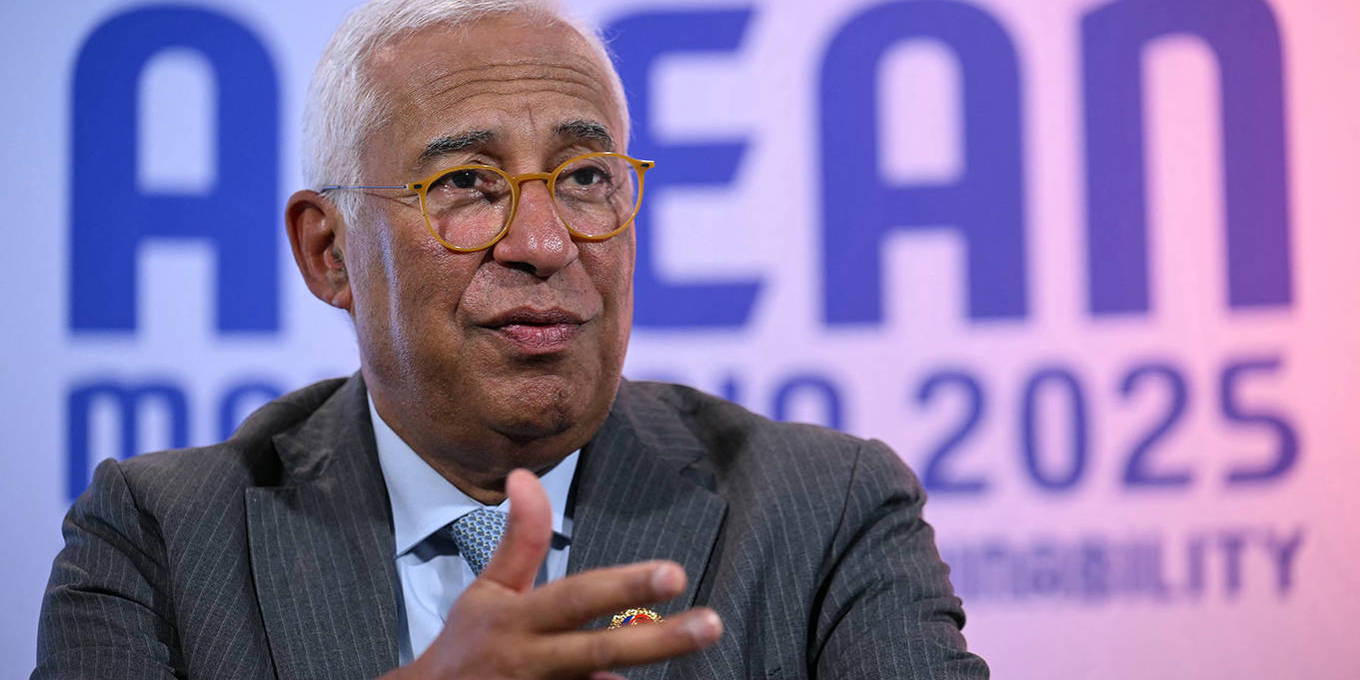

OXFORD – At the recent ASEAN Summit in Kuala Lumpur, European Council President António Costa outlined Europe’s strategic posture. “The European Union,” he said, “is proud to engage with ASEAN as a reliable partner in today’s shifting geopolitical environment.” His remarks echoed those made four months earlier by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, who proposed teaming up with the 12-member Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). European leaders’ ongoing efforts to seek and strengthen “reliable” partnerships are largely motivated by US President Donald Trump’s attempts to force allies to pay more for American security guarantees and military aid, as well as by his steep and often arbitrary tariffs. Trump himself underscored this strategic imperative the day before Costa’s remarks, when he announced an additional 10% levy on Canadian goods in response to a provincial ad in Ontario quoting former President Ronald Reagan as saying that tariffs “hurt every American worker and consumer.” This instability presents Europe with a unique opportunity to offer an alternative to overreliance on either the United States or China. Seeking to position his country as a counterweight to American assertiveness, Chinese President Xi Jinping has framed his foreign policy as a “clear stand against hegemonism and power politics.” Speaking at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit in September, Xi – flanked by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Russian President Vladimir Putin, and 17 other heads of state – pledged to “practice true multilateralism” and promote a global order based on free and open trade. Yet many leaders remain wary of Xi’s assurances. China’s bilateral offers have grown more conditional, and its bullying of the Philippines and other countries in the South China Sea has become increasingly overt in recent years. At the same time, the country’s economic slowdown has curtailed the extensive overseas financing it once provided and dampened Chinese demand for commodities like iron ore and soybeans from developing and emerging economies. To seize this opportunity, the EU must rethink its geopolitical comparative advantage. While an older generation of European leaders continues to tout the bloc’s social model, shared values, and generous aid programs, these once-powerful assets have lost much of their appeal – even within Europe itself. Across the continent, younger people feel ill-served by social systems their countries can no longer afford. The postwar “European values” that long served as unifying ideals are now being contested in Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and beyond, as centrist parties lose ground to a resurgent far right. Meanwhile, aid and humanitarian budgets are increasingly squeezed by rising defense costs and tighter fiscal policies, leading Europe’s traditional partners to seek something more tangible. Europe’s future influence will hinge less on values and aid, and more on economic opportunity. Unlike China – and increasingly the US – the EU remains a vast and open market, welcoming foreign direct investment. Easy access to the UK, Switzerland, and Norway further strengthens its position. Moreover, Europe’s so-called “periphery” is far more dynamic than many assume. European commentators frequently lament the continent’s sluggish growth, but they tend to overlook the vitality of economies such as Malta, Ireland, Cyprus, Poland, Croatia, Spain, Greece, Slovenia, and Bulgaria, all of which are growing faster than the continental average. The same is true of technology and finance. While the EU is often dismissed as a referee rather than a player in tech and private equity, emerging European startups are beginning to challenge that stereotype. But there is much more to be done. For starters, policymakers must act on former European Central Bank President Mario Draghi’s report on EU competitiveness, which called for up to €800 billion ($922 billion) in additional annual investment to meet the bloc’s defense, infrastructure, clean energy, and AI goals. A good start would be to offer Europeans a clear picture of the envisaged destination. Fortunately, the EU has the resources to advance its strategic objectives. It can do so by harnessing its capital-markets union, by nurturing an innovation-friendly ecosystem, and by securing affordable, sustainable energy supplies. It could also make better use of the European Investment Bank, whose substantial capital and mandate remain underused. Importantly, EU leaders must resist the temptation to pursue partnerships through regulation or moralizing. Other countries are not attracted by a Europe that imposes rules unilaterally or mimics the heavy-handed tactics of major powers. Instead of threatening carbon tariffs or supply-chain exclusion, the EU should promote cooperative ventures – technology sharing, concessional finance, and joint clean-energy projects – anchored in mutually agreed monitoring and accountability standards. Europe’s defense capabilities have long been constrained by fragmented decision-making, overreliance on NATO, and a balkanized industrial base unable to scale in wartime. But Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has jolted Europe out of its complacency, uniting the continent, driving up military spending, and accelerating investment in new technologies. Rearmament efforts must focus on innovation and efficiency rather than political patronage. That means reforming procurement systems weighed down by pressures to create jobs for key constituencies. Europe should also prioritize developing its own capabilities over awarding contracts to US firms. Only then can it position itself as a credible security partner. Politically, the EU’s greatest strength lies in its deep-rooted tradition of cooperation through law and institutions. This provides a robust foundation for stable, noncoercive, mutually beneficial partnerships and enhances the bloc’s credibility as a defender of smaller states, both within and beyond its borders. For many midsized countries seeking reliability and consistency, that is precisely what makes Europe appealing. Although it may seem dull, the EU’s legalism is a strategic asset. Where governance in the US can hinge on personality politics, and in China on centralized control, Europe’s rules-based systems provide a degree of stability few others can match. So long as the bloc upholds its commitment to the rule of law, its predictability will remain one of its most powerful competitive advantages.