Copyright theconversation

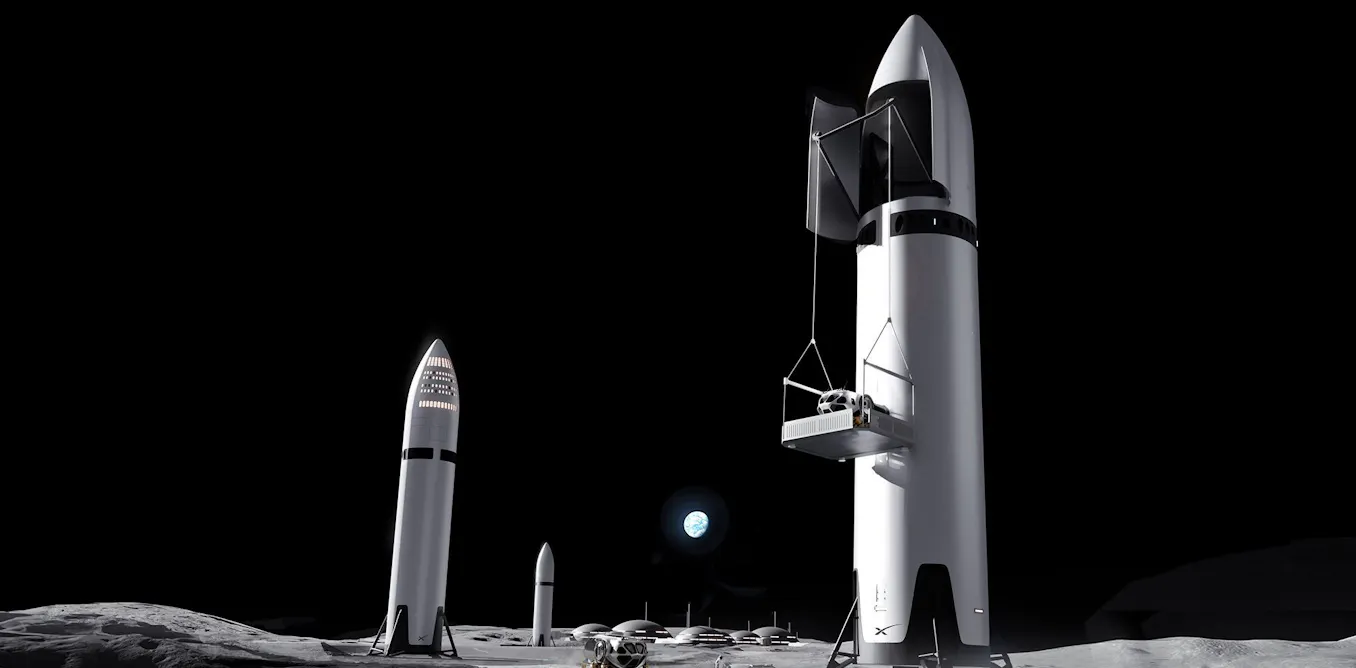

Elon Musk’s company SpaceX and Jeff Bezos’ company Blue Origin have submitted simplified plans to Nasa designed to return US astronauts to the Moon’s surface. These plans focus on Nasa’s Artemis III mission, which will see the first US astronauts walk on the Moon since Apollo 17 in 1972. SpaceX was awarded the contract to build the lunar landing vehicle for Artemis III in April 2021, using a version of their Starship spacecraft. On October 20, 2025, Nasa’s acting administrator, Sean Duffy, said he was reopening the contract to competitors, such as Blue Origin, citing delays with Starship. So what has gone wrong? At the heart of the issues are Starship’s size and ambition. The massive spacecraft will tower over the moonscape at 50m (165ft) tall and aim to bring 100,000kg of payload to the lunar surface. Space vehicles designed to carry humans undergo a process of certification to become “human-rated” – safe to put crew and passengers on board. Most undergo numerous tests of their component parts, followed by a few tests of the full vehicle. However, Starship’s test flight programme is now the longest in space launch history. The Starship upper stage is the part that will carry astronauts. It underwent seven small launches up to 12.5km in altitude between 2020 and 2021. Only the last of these flights, SN15, survived touchdown. There have now been 11 test flights to orbit of the full Starship system, where the upper stage is paired with a Super Heavy rocket booster. Most have ended poorly for the upper stage, with the last two surviving re-entry before tipping over after landing on the ocean and exploding. It is hard to forget the first time the pair of the SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket’s boosters returned to the launch pad and landed successfully, or the first time the Starship Super Heavy booster was caught by the arms (or “chopsticks”) on its launch tower. But it is also hard to forget the live video of Starships losing material during re-entry, the fiery remains of their break up streaking across the sky during Starship’s test flights 7 and 8, or the upper stage that exploded in a fireball on the pad in June 2025. The development of Starship vehicles is unique and SpaceX aims for frequent launches with as much progress as possible in between them. It is accepted that these losses will lead to improved technology and safety down the line. However, the line is short. Nasa’s acting chief Sean Duffy has expressed concerns about Starship’s progress towards the Artemis III mission, which is scheduled for 2027. A few days after Duffy’s comments, SpaceX posted an entry about the Moon programme on its blog. In it, the company said: “Starship continues to simultaneously be the fastest path to returning humans to the surface of the Moon and a core enabler of the Artemis programme’s goal to establish a permanent, sustainable presence on the lunar surface. SpaceX shares the goal of returning to the Moon as expeditiously as possible.” SpaceX also said that it had completed 49 milestones aimed at landing astronauts on the Moon and that “the vast majority” of contractual milestones had been achieved “on time or ahead of schedule”. Starship’s advertised payload to orbit of 100,000kg sounds impressive. But on its most recent test flight, Starship carried a dummy payload of just 16,000kg – less than the 22,000kg maximum payload for SpaceX’s workhorse rocket, the Falcon 9, and Starship promises ten times that. Engineers have a long way to go before the system can carry the equipment needed for a Moon mission, let alone astronauts. The bottom line is that the payload-to-orbit promise has not yet been demonstrated. Design philosophy is a major reason we have arrived here. SpaceX isn’t designing and building a lunar landing vehicle. They are building a do-anything super-heavy-lift launcher capable of sending payloads to Earth orbit, to the Moon, or even to Mars, and landing on any one of those bodies. The success of past and current space missions comes from focus. Spacecraft are designed to solve a number of very specific problems, overcoming their missions constraints. A recent experience at the European Space Agency’s (Esa) Concurrent Design Facility (CDF) showed how this works in practice. This is where scientists and engineers collaborate to find trade offs for mass, power, propulsion and budget until a spacecraft design is finalised. Spaceflight succeeds through clever fixes to specific problems, not grand gestures. Because Starship needs to refuel in Earth orbit before travelling to the Moon, a single lunar mission will require a dozen launches or more. The additional flights will launch versions of Starship intended solely to refuel another vehicle. If Starship works, it will be fantastic, but aiming for size instead of application is why it is not ready for Artemis III. Nasa’s trajectory Another aspect to this is the leadership and direction of the US government, which guides Nasa. The current American Moon programme was started under the George W. Bush administration over 20 years ago and has been undergoing drastic reconfigurations every few years. With a major US election every two years (presidential and congressional), Nasa’s direction hasn’t been stable enough to manage long-term, large-scale planning. Esa, conversely, sets objectives on a ten-year scale, and moves towards them steadily. It is hard to see problems easing with the US Artemis lunar programme, especially under a president who has requested the agency’s budget be dramatically slashed. The budget proposal would terminate US participation in many international space missions, such as EnVision, Lisa and NewAthena. Additional funding would be needed from other nations to make up the shortfall; otherwise the programmes could end. The loss of US participation in these projects will, in turn, affect how other countries are involved in Artemis. Artemis relies strongly on international support for a number of elements, such as the Orion service module that carries astronauts to the Moon and segments of the Lunar Gateway space station, where astronauts would board their SpaceX or Blue Origin lunar landing vehicles. Whichever company ends up carrying astronauts to the Moon on Artemis III, and whatever their “simplified plans” look like, there will be exciting things to see in the next year or two. These include the Artemis II mission (which will send four astronauts on a lunar flyby), the first launches of Blue Origin’s New Glenn heavy lift rocket, and commercial payloads launched to the Moon by both SpaceX and Blue Origin.