Brothers Nadim and David Khoury left Boston for the West Bank in 1993, convinced that the newly signed Oslo Accords meant a Palestinian state would soon be born.

More than three decades on, Nadim’s children, Canaan and Madees, now run the family business — a successful microbrewery in the predominantly Christian village of Taybeh on the outskirts of Ramallah — a city once seen as the center of any future Palestinian nation.

Nadim is still waiting.

“Our logo is the brewery in the hands of Taybeh, with the sunrise — we put the sunrise there as a bright future for Palestine,” the 66-year-old said. “We are not asking for much, we want to live a normal life,” he added, “we want to live side by side.”

France plans to use the annual United Nations General Assembly in New York as a platform on Monday to become the first major Western power to recognize an independent Palestine alongside Israel, joining around 147 countries that already do and pushing more to follow suit. The UK and Canada have indicated they may do so. The moves were condemned by Israel and its closest ally, the US, which banned senior Palestinian officials from attending the annual UN gathering.

The French initiative is part of a joint effort with Saudi Arabia to end the war in Gaza, the smaller of the two Palestinian Territories, which began after Hamas attacked Israel in October 2023, killing around 1,200 people and kidnapping roughly 250 others. Israel’s retaliation against Hamas — which ruled Gaza and is considered a terrorist group by the US and European Union — has killed at least 64,000 Palestinians, according to the Hamas-run health ministry. The ensuing humanitarian crisis has lost Israel international support and risks turning the country into a pariah state, say critics.

But the reality on the ground in the West Bank, including in Ramallah, reveals that for the territory’s 3 million Palestinians, the diplomacy can’t disguise that the viability of such a state is crumbling.

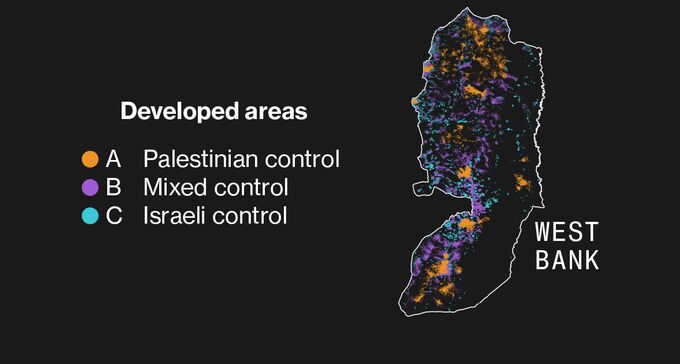

Through settlement expansion, rising violence by extremist settlers and Israeli military activity, land under Palestinian control in Area A has become what Majdi Malki, a sociology professor at Birzeit University, outside Ramallah, calls “170 isolated islands.”

Traveling from one community to another — even for medical reasons, education or work — has become so difficult and dangerous that many people who spoke to Bloomberg News said they choose not to. The economy, already struggling before the war, is plunging into a deeper crisis, with gross domestic product contracting by around 22% last year.

“Recognition is symbolic and politically important,” said Palestinian economy minister Mohammed Alamour, “but what does it mean when the patient is dying? It’s not enough.”

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s government says a Palestinian state would reward Hamas for October 7 and serve as a base for terrorists to attack Israel. He has threatened to annex large parts of the West Bank, and his finance minister, Bezalel Smotrich, has said the plan for the new housing units outside Jerusalem “definitively buries” the idea of state recognition.

The best Palestinians can hope for, Malki believes, is limited autonomy, with far less sovereignty than before. “We’re living in an environment that pushes people away — a repelling climate,” he said. Gradually, the West Bank “will empty.”

It was supposed to be very different. Taybeh Beer was found in many Tel Aviv bars in the 1990s, when Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization were negotiating. Under the Oslo Accords, the PLO recognized Israel and Israel recognized the PLO, and set up an interim governing system in Gaza and the West Bank. Most people assumed that would lead to “a two-state solution,” with a nation of Palestine on most of the land captured by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War, and a corridor linking the West Bank to Gaza, just 80 miles away.

Opponents of the deal worked to stop it. There were periods of devastating Palestinian suicide bombings in Israeli cities and sporadic settlement expansion. All along, major differences prevented agreement: borders, the future of Palestinian refugees displaced in 1948, the long-term control of parts of Jerusalem — a city considered holy by both sides — and security arrangements.

In 2000, after another failed negotiation, the second Palestinian intifada, or uprising, erupted. Israel began erecting the separation barrier, dividing Israelis and Palestinians from each other, and from Jerusalem. Land grabs and settlement expansion accelerated. Hamas won legislative elections in 2006. Israel voted in a government that included officials who emerged from a party once banned from politics for its extremism, in 2022.

Netanyahu’s government launched its retaliatory war on Gaza with the stated goal of eradicating Hamas and retrieving the hostages — around 48 of whom are still being held. It also tightened control over the West Bank, with its biggest military operations since the intifada, designed to keep Israelis safe, it said.

In Ramallah, a city of roughly 46,000 people that has grown by several thousand since the war, according to the local bureau of statistics, Palestinians say those measures — ranging from new iron gates and checkpoints to military raids — are making life intolerable and strangling any chance of a future Palestinian state.

At Birzeit University — one of the West Bank’s oldest — a little more than half of the students live in Jerusalem and Ramallah but many study via zoom.

A 27-year-old who asked to be identified only as Mohammed for his own safety said he fears arrest or injury each time he leaves his house. “This land is in a struggle with the occupation until the end of time,” he added.

“The situation is terrifying,” said another who asked only to be identified as Aisha, also out of concern for her security. “You can’t plan for the future when you’re afraid of the present.”

Cars are backed up in long lines at the city’s main entrances as they are searched at checkpoints by Israeli soldiers. Settlers have hoisted Israeli flags, previously only seen during holidays, along a 5-kilometer stretch of the highway linking Ramallah to Nablus. Out of 22 new settlements approved by the Israeli cabinet in 2025, five sit just outside the city. This area has grown over the years to become home to around 180,000 Israelis, or around 20% of the total West Bank settler population.

The West Bank economy is facing its worst crisis ever, according to the Palestinian Authority.

Israeli officials revoked the permits that allowed 200,000 Palestinians to work in Israel, whose income was a vital source of cash for the territory. They have also held back around 10 billion shekels worth of customs and VAT revenue on goods over the past two years, according to the Palestinian Authority, saying the funds — which the PA used for services in Gaza before the war as well as public sector salaries — could benefit Hamas. International aid has dwindled. Tourism to cities like Bethlehem and Jericho has collapsed, and the businesses that relied on it are struggling. Unemployment has surged to touch more than half of working-age people.

Ramallah’s US-style Icon Mall, which opened this year along the road to Birzeit University — to sharp criticism from many Palestinians, given the war in Gaza — was empty on a recent weekday, though its 165 shops and food courts get busier on the weekends. Restaurants favored by diplomats are quiet, after they were advised not to visit the territory given the volatility — more than 1,000 Palestinians have been killed, mostly in Israeli military operations, as well as 25 Israelis, including members of the security forces. Cafes no longer heave with people arguing about politics over tea.

The UN summit “should be an opportunity for the world to say no to the current Israeli government, no to the war on Gaza and the West Bank,” said Sabri Saidam, the deputy head of Fatah’s Central Committee, the decision-making body of the secular party, which runs the PA. “If the world fails to pick up this opportunity, I think the Palestinian people will certainly give up.”

Soon after opening their brewery, the Khoury brothers developed a sideline pressing olive oil to help farmers pay for their children’s education — the village only has private schools. The family business quickly expanded. They make gin and wine with local grapes as well as two dozen different types of beer, including an IPA and a non-alcoholic variety. They held festivals for tourists and ship products to 17 countries, from Chile to Japan and the UK.

The Taybeh Brewing Company survived the second intifada, four previous wars between Israel and Hamas in Gaza that also had repercussions on the West Bank, and the Covid 19 pandemic. Selling alcoholic beverages in a conservative part of the world has, at times, presented challenges. Governments that don’t recognize a Palestinian state have refused to import bottles bearing the name Palestine, so they’ve had to change labels.

Over the last two years the Khourys shut their 80-room hotel. Plans to move the brewery into a bigger facility with new fermenters are on hold as they wait for parts to arrive from overseas. They continue to ship abroad, but obtaining Israeli export permits can now take weeks. They worry more about access to water.

The Oslo Accords specified the amount of water Palestinians would get during what was meant to be a five-year interim period before statehood, but while the population has grown, the amount of water they’re allocated hasn’t. The Israeli-run Civil Administration has barred Palestinians from digging wells, and Israel accuses Palestinian farmers of stealing water by tapping into Israeli pipes.

In the valleys to the north and northeast of Ramallah, where Taybeh is located, extremist settlers are adding to the difficulties.

The Hilltop Youth group is increasingly active across this area, according to Palestinian authorities. Described by former Israeli premier Ehud Olmert as “a kind of private militia” that is “very aggressive, very violent,” its members have been adding caravans to outposts — often precursors to settlements — and entering communities where they have been accused of terrorizing locals. Culture minister Emad Hamdan was surrounded and held for around three hours last month on an official visit to the village of Kafr Ni’ma.

These settlers allow their cows to graze in the Khoury’s wheat and barley fields. Canaan and Madees’s uncle was shot at while harvesting olives. And in July a field near the ruins of Taybeh’s Byzantine church was set on fire — drawing a rare rebuke from Mike Huckabee. The US ambassador to Israel has previously sided with settlers, saying he agrees with them that Israel has historic rights to the territory they call Judea and Samaria.

“Just two years ago, my friends would come and we used to go hiking around the mountains. We don’t do that anymore,” said 34-year-old Canaan, who left Taybeh to study mechanical engineering at Harvard University. “We’ve been more afraid. There’s less access to our land … we darkly joke that we’re building a new brewery for the settlers so they can come and take it.”

“Anyone with a business would like to expand and grow, but we are also realistic,” Canaan added. “It’s hard to put a huge investment somewhere where there is such a high political risk, which is only increasing by the day.”

A state needs credibility and a government with authority but the Palestinian Authority is short on both. Palestinians haven’t voted since 2006. Fatah — the largest faction of the PLO — fought a civil war with Hamas that ended with the Islamist group splitting from the West Bank and taking control of Gaza the following year, and led Israel and others to impose a closure on the strip. Many people Bloomberg spoke to said they have grown increasingly disillusioned with octogenarian President Mahmoud Abbas and his administration.

Malki, also director of the Ramallah-based Palestinian Institute for Studies, said that while the Palestinian Authority kept health and education services running, coordinated on security matters with Israel and supported cities, it could have done more to raise awareness about land rights. He said the PA should have warned rural communities that Israel could seize plots of land left uncultivated for three years.

Ultimately, though, he said the PA was powerless. “Any government or authority operating under occupation,” Malki said, “would find it very difficult to stop these developments.”

Inside the government complex in Ramallah’s Al-Masyoun neighborhood, Palestinian officials are focusing on trying to win trust. They have a blueprint for rebuilding the ruins of Gaza, where a UN-commissioned report this week said Israel was committing genocide. In northern parts of the West Bank, where the PA has lost control, replaced by local armed groups, Israeli airstrikes, tanks and bulldozers have flattened entire neighborhoods and destroyed key infrastructure.

In June, Abbas sent a letter to France’s President Emmanuel Macron and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia, promising to improve governance and hold elections “throughout the Occupied Palestinian Territory,” including East Jerusalem, within a year. He stressed that only “political forces and candidates that clearly accept the Palestine Liberation Organization platform” will be allowed to run, in an effort to sideline groups like Hamas, which don’t recognize Israel’s right to exist. Abbas also condemned the October 7 attack, describing it as “unacceptable” and calling for the immediate release of all hostages.

Read more: The War in Gaza Leaves Toxic Legacy of Garbage, Disease and Pollution

As leader of a country that’s home to Europe’s largest Jewish and Muslim communities, Macron believes peace will only come to the region with a Palestinian state working closely with its political and financial backers in Europe and the Arab world, people familiar with the French president’s thinking said. While he understands that reversing facts on the ground would be difficult, Macron’s idea is to prepare for the day after a ceasefire in Gaza, the people said.

He insists this would also help save the Abraham Accords — that saw the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Morocco establish diplomatic relations with Israel during President Donald Trump’s first term, and is in jeopardy after the recent Israeli strike on Hamas leaders in Qatar. Saudi Arabia, the largest Arab economy, has pledged not to normalize without a path to Palestinian statehood. Indonesia, the world’s biggest Muslim nation, is ready to make the move once Israel recognizes an independent Palestine.

Countries including Belgium and New Zealand may join the French push at the UN gathering. If the UK were to also follow suit, as it’s expected to, it says that would be because Israel failed to take “substantive steps” to agree to a ceasefire in Gaza, and it would come with demands that include Hamas’s release of all hostages. The US would then be the only member of the UN Security Council not to recognize a Palestinian nation.

Macron’s efforts have fueled tensions with Israel, which has threatened to shut the French Consulate in Jerusalem. But he believes the biggest hurdle is Trump, not Netanyahu. The French leader knows only the US can pressure Israel, the people said.

Still, the hope for Palestinian officials is that a mass recognition will somehow help reshape the political landscape. If governments with strong economic, security and military ties with Israel were to use their leverage, Alamour, the economy minister, said, “they could halt all this within a week.”

Read More: EU Proposes Suspending Israel Trade Perks Over Human Rights

Many Palestinians on a small plot of land outside eastern Jerusalem — called E-1 — said the two-state solution is already dead. Both Israelis and Palestinians are banned from building on it under the Oslo Accords, pending a final peace deal. But over the years, settlements have silently grown.

This is where the new housing units that Smotrich, the Israeli finance minister, announced in August will be located. In addition to effectively cutting the West Bank in two from north to south, the territory will become further disconnected from East Jerusalem, and Palestinian land expansion in Area C will be impossible. Travel time would increase and geographical contiguity would be permanently cut.

“This corridor — if it’s lost — then the entire project of a Palestinian state is at risk,” said Eid Khamees Swelem Jahalin, a 60-year-old Bedouin leader in the village of Khan Al-Ahmar, which will be demolished to make room for the new units, as well as a new road.

Roughly 7,000 Palestinians will have to move, their land and assets will be seized. Some of them live and own businesses in the town of Al-Eizariya, but most of them are Bedouin shepherds and farmers who are spread across 22 communities, including on land gifted to the Vatican by Jordan in 1964. They’ll likely end up in cities, their leaders said, heaping pressure on stretched services, and forced to abandon a centuries-old way of life.

Israeli authorities planned to demolish Khan Al-Ahmar before, but were blocked by an international solidarity campaign that ended with Fatou Bensouda, the then-Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, saying in 2018 that such an act would be considered a war crime and a violation of international law.

Given the current geopolitical climate, Eid said he expects Israel’s complete annexation of the West Bank.

“I tell my community about the reality on the ground so no one gets shocked later and says, ‘Why didn’t you warn me?’,” Eid said. “I say: ‘this is the reality. You’re standing in the storm now. If you can endure it — welcome. If you want to leave — this is Palestine — Go.’”