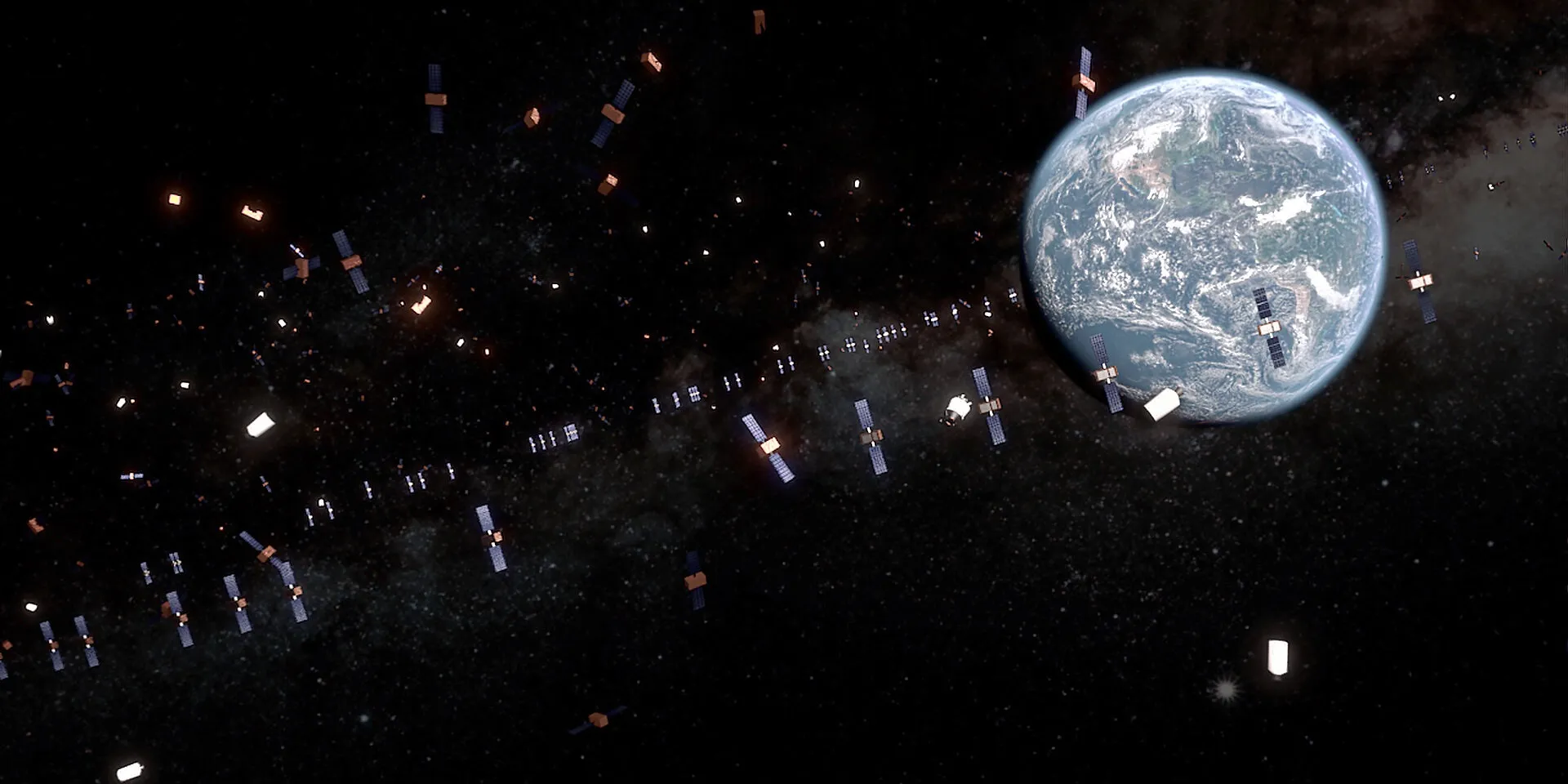

Space is changing, fast. Thousands of new satellites are going up each year. Thousands of new satellites are being launched each year, with broadband constellations, Earth observation systems, defense platforms, optical relays and sovereign payloads are all jockeying for position in low Earth orbit (LEO). Orbital debris mitigation, which used to be a niche regulatory issue, is now a front-line risk to commercial operations, government capabilities and long-term access to space.

For now, the system is mostly working. The FCC’s orbital debris rules, especially the five-year post-mission disposal requirement and operational altitude standards, have largely succeeded in what they set out to do. Major players like SpaceX and Amazon’s Kuiper are taking debris mitigation seriously. SpaceX moved its Starlink constellation to lower altitudes to reduce debris risk, and Amazon’s Kuiper plans to use propulsion and active deorbiting to comply with disposal rules. These companies track their constellations with care and engineer for controlled deorbiting.

But, truthfully, this is a flashing warning light. Because what we have now is a set of policies designed to avoid disaster — not to manage the scale, complexity and geopolitical volatility of today’s space ecosystem.

The next phase of debris management is about keeping the system functional as LEO gets more crowded, more contested and more central to both global commerce and national security. We need to evolve the rules urgently.

That means moving beyond altitude-based blanket rules toward more dynamic models that take into account capability, propulsion and mission profile. It means differentiating between risk categories. And it means developing a real solution for international coordination, especially when major actors like China, Russia and India aren’t aligned with U.S. orbital debris and space traffic management frameworks. If we don’t, we risk regulatory gridlock while the rest of the world builds and launches. Worse, we risk creating perverse incentives that would punish good actors while others operate with impunity.

In the meantime, there’s a lot companies can do to stay ahead:

Plan for conjunctions like they’re inevitable. In a crowded LEO, they are. Most close calls aren’t the result of bad actors or poor planning. They stem from the unpredictability of space and the reality that many propulsion-less satellites are falling more than flying. Companies need playbooks for what to do when they get a warning from JSpOC (now CSpOC), which provides conjunction warnings and space situational awareness for U.S. and allied satellites. This should be part of mission design, not a scramble in real time.

Re-evaluate propulsion. Yes, it’s expensive. But propulsion buys you flexibility — in your deployment altitude, in how long you can stay operational and in your ability to comply with post-mission disposal. Right now, many operators are flying low to ensure reentry within the FCC’s 5-year rule. But that often shortens mission life unnecessarily. Propulsion lets you fly higher, stay longer and still come down safely. The ROI math may be more favorable than you think.

Add value through awareness. Remote sensing, interstellar links and even basic situational awareness systems are becoming essential. These aren’t just nice-to-haves — they’re strategic differentiators in a future where visibility, responsiveness and resilience matter.

Push for practical fixes, like Wi-Fi in space. One of the most absurd hurdles operators still face is that using Wi-Fi in space is considered a nonconforming use under current FCC and ITU regulations. But enabling inter-satellite comms would improve rendezvous, proximity ops and debris avoidance.

Get involved in shaping policy. Even if your business isn’t defense-oriented, your customers are thinking about national security. The U.S. Space Force, SDA and allied governments are investing heavily in resilient commercial partnerships. Your biggest customer may be a government that wants systems hardened against interference, EMP, or worse. Design for that now, not later.

If you’re a commercial operator today, your long-term viability depends on the sustainability of the space environment, and your ability to adapt to fast-changing policy, technical and geopolitical pressures. I see too many companies that experience operations costs and constraints due to orbital debris compliance. The smart ones (the ones who’ll win the next decade) are the ones who treat orbital sustainability as part of their business model.

You don’t need to have it all figured out. But you do need to start acting like your operations exist in a crowded, evolving, high-stakes environment — because they do. Companies need to be aware of the risks and opportunities created by this environment in order to navigate and succeed in it.

The orbital debris problem won’t explode overnight. That’s the danger. It will creep up through overdeployment, through unresponsive or adversarial actors, through aging rules that don’t match operational reality. We still have time to fix that.

Will Lewis serves as Of Counsel at Aegis Space Law, focusing on the regulatory, licensing and spectrum challenges facing today’s satellite and space operators. He brings extensive experience working before the FCC and other federal agencies to support clients’ licensing strategies, compliance obligations and long-term policy objectives.

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion@spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine. The perspectives shared in these opinion articles are solely those of the authors.