Millions of Americans who could benefit from GLP-1 weight-loss drugs are caught in the middle of a battle between drug companies and insurers over their costs, leaving them without coverage even as evidence mounts that the drugs could stave off expensive health complications in the future.

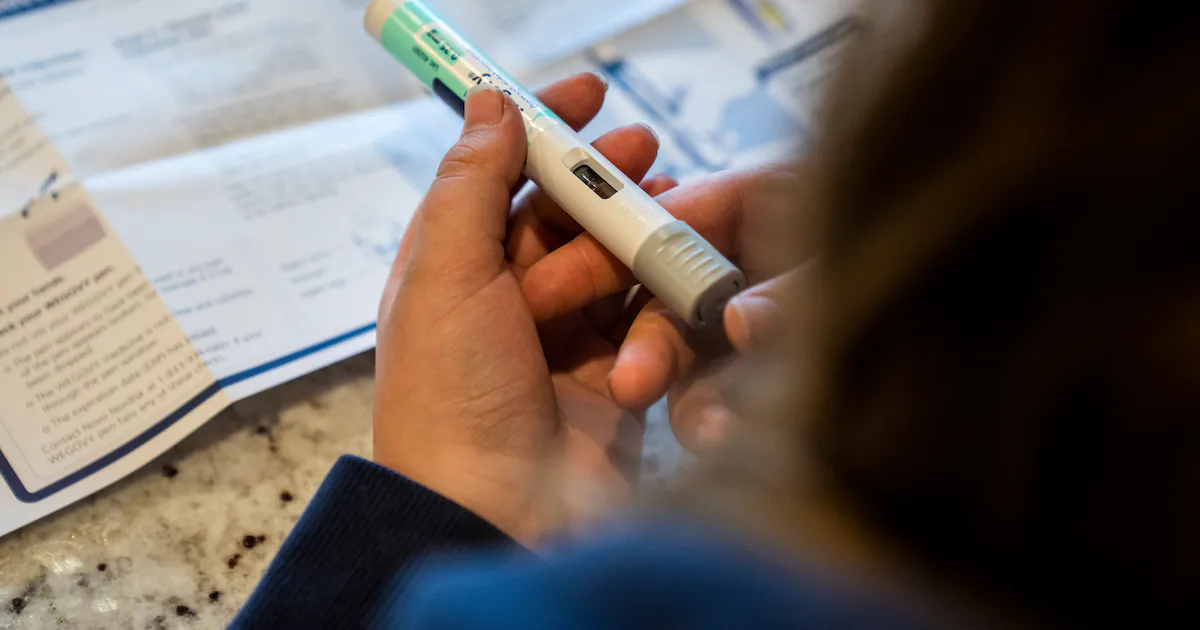

Insurance coverage for the drugs has barely budged in the last year. Eli Lilly said in August that around 50 percent of employers had chosen to cover its weight-loss drug, Zepbound, little changed from a year earlier. Novo Nordisk said last month that about 40 million people have access to anti-obesity drug Wegovy through commercial insurance, roughly the same as at the end of 2023.

Evidence from clinical trials shows that GLP-1 injections have benefits far beyond weight loss, helping prevent people from developing diabetes or suffering a heart attack years down the road – improving lives and ultimately blunting costs for health plans. But while the savings might only be realized over decades, experts say, the prescription costs must be paid starting now, threatening to overwhelm health plans’ financial reserves because of their immense popularity.

Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk, which dominate the weight-loss market, brought in combined sales of about $14 billion in 2024 from Zepbound and Wegovy, and face intense public and political pressure to bring down the costs, which can run to $6,000 a year even at a discounted rate.

Both companies are racing to win approval for next-generation weight-loss pills – which are expected to set off even greater demand and become instant blockbusters.

With the drugmakers and insurers at a stalemate over coverage, some analysts say a new financial analysis from an influential nonprofit might begin to move the needle.

The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, which studies the value of prescription drugs, published preliminary findings earlier this month that found tirzepatide and semaglutide – the active ingredients in Zepbound and Wegovy – are highly cost-effective when measuring health benefits over a lifetime. But with obesity afflicting a huge share of the U.S. population, treating people at that scale “raises serious concerns about affordability,” the report said.

If the GLP-1 drugs were treatments for a disease afflicting a small population, “we’d go, ‘this is fantastic,’” said David Rind, ICER’s chief medical officer. “But if you want to give these drugs to 40 percent of the U.S. population, it doesn’t matter that these drugs are cost-effective,” he said, referring to the ability to pay for them. The scale of who could benefit from GLP-1s, he said, is “probably almost unique.”

About 1 in 8 adults has taken a GLP-1 drug, according to a 2024 KFF survey.

There is no generic version of the most popular GLP-1 drugs. Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly have rolled out discounted versions for people whose insurance doesn’t cover Wegovy or Zepbound for around $500 a month, and they’ve faced competition from compounding pharmacies creating off-brand versions – a practice that is being litigated in courts across the nation. (Another well-known GLP-1 drug, Novo Nordisk’s Ozempic, is approved to treat diabetes, though it is commonly used for weight loss.)

The drugmakers as well as the health-insurance industry saw the cost-benefit findings in the ICER report as validation.

“We are pleased to see that ICER continues to reaffirm that Wegovy is cost effective,” Novo Nordisk said in a statement.

Eli Lilly said in a statement that it is “confident in the body of clinical and economic evidence supporting Zepbound and its value to patients, the health care system and society.”

Chris Bond, a spokesperson for AHIP, which represents the health-insurance industry, said the report “further confirms Americans’ growing concerns about affordability and sustainability in our health care system in light of the exorbitant prices drugmakers set and which they alone can lower.”

Insurers have warned that absorbing such costs is pushing up premiums, and some plans have stopped covering GLP-1 drugs for obesity.

One complication for health plans is that patients they cover often switch jobs, so they might not reap the potential long-term financial benefits of covering a GLP-1 drug for a patient who ends up at another plan. But if health plans broadly covered the medication for weight loss, they would gain patients who had been taking a GLP-1 and still realize the benefits, analysts say.

“But at the moment, this logic is not prevailing, and instead the GLP1s are commonly felt to be a budget-busting line item with no immediate offsets,” Bank of America analysts wrote in a note to clients earlier this month. The analysts argued that GLP-1 drugs aren’t actually expensive as an obesity treatment, citing their benefits as well as their price relative to some expensive drugs for other chronic diseases – such as asthma and autoimmune disorders.

ICER’s analysis looked at studies of people with obesity who didn’t have diabetes, and used an estimate of the drugs’ price after rebates and discounts. It calculated that taking semaglutide or tirzepatide would provide health benefits relative to lifestyle interventions alone, a far better deal than most prescription drugs it analyzes, Rind said.

As with most medications, he said, the drugs “don’t save more money than they cost.” But ICER found that they substantially improve lives while meaningfully curbing a share of the lifetime cost. Taking semaglutide or tirzepatide is estimated to offset the lifetime costs of treatment by $46,725 and $61,500, respectively, according to the report.

Not all research has reached the same conclusion. A paper published in March by University of Chicago researchers found that semaglutide and tirzepatide produced better lifetime health gains than other weight-loss drugs but “are not cost-effective at their current net prices.”

Jennifer Hwang, the paper’s lead author, said she’s in the process of updating her model to include more recent price estimates and include additional benefits of the drugs, which she expects will result in a cost-effectiveness calculation “similar to what ICER has now.”

Wall Street analysts were hopeful that ICER’s finding could lead to more insurance companies covering the drugs for weight loss.

“Though commercial coverage is still highly dependent on the employer, we think having ICER’s backing could positively influence public and political perception of obesity treatments using GLP-1s, and subsequently increase pressure for coverage,” Geoffrey Meacham, a Citi Research analyst, wrote in a note to clients earlier this month.

A key part of the value of GLP-1 drugs is that their benefits extend beyond losing weight. ICER highlighted semaglutide’s potential to improve outcomes in knee osteoarthritis, a liver condition and heart failure, while tirzepatide has been shown to reduce the risk of diabetes and treat sleep apnea.

There are significant uncertainties that could change the cost-benefit analysis, including the unknown impacts of taking GLP-1 drugs for a lifetime, the effect of starting and stopping them, and additional benefits that are still being explored in clinical trials.

The Trump administration is exploring allowing Medicaid and Medicare plans to voluntarily cover GLP-1 drugs for “weight management,” The Washington Post previously reported. To participate, the plans would also need to provide coaching on diet and exercise for patients.

– – –