Copyright thespinoff

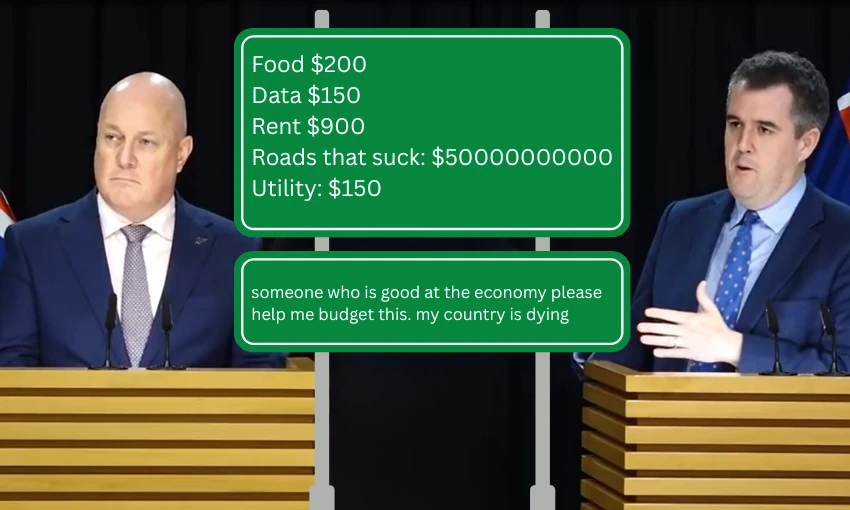

At this point, the New Zealand government is just a road-building authority with bits tacked on. And not even a very good one. In July last year, the Infrastructure Commission delivered a stark warning about the exploding costs of the Northland Corridor highway. “We are concerned about the process by which this project has been identified as being of such high priority for delivery, amid scarce funding,” the report said of the four-lane expressway connecting Auckland and Whangārei. “Overall affordability constraints and the need for careful project selection will not be solved by financing tools.” In other words: the government is obsessed with finding fancy new ways to fund big infrastructure projects. But the far, far bigger problem is that the government keeps building roads that suck. Last Monday, transport minister Chris Bishop and prime minister Christopher Luxon announced $1.2 billion in funding for initial design work and property acquisition for six new roads as part of the government’s Roads of National Significance programme. From the little information we’ve been given about them, these roads also appear to suck. The investment cases released by the government are short on detail; two-page summaries with some optimistic timelines and a few coloured lines showing where the roads will go. The benefit-to-cost ratio NZTA calculated for most of them is embarrassingly low. The second Mt Victoria tunnel in Wellington has a BCR of 1.0, meaning that the government wants to spend $3.8 billion on a project with no net benefit. Others on the list aren’t much better: the Hope Bypass in Nelson is estimated at 1.1, Hamilton Southern Links is at 1.6, and Petone-to-Grenada in Wellington is 1.7 (assuming they are tolled, which Bishop says is the government’s starting point). As Matt Lowrie of Greater Auckland points out, these already unimpressive numbers would be even worse if they weren’t juiced by some convenient maths. Earlier this year, NZTA changed the way it calculated benefit-to-cost ratios, increasing the benefits and discounting some of the costs. “This means projects that previously barely qualified as economical now suddenly generate more benefits than costs – and all now magically clear the (very low) hurdle of a BCR of 1.0. There was a time when a BCR of 3.0 was the minimum for spending public funds on this scale,” Lowrie writes. These roads are bad value per-dollar, and they cost lots and lots of dollars. Infracom warned that the Northland Corridor will consume 10% of all government spending on infrastructure over the next 25 years. That’s not just transport infrastructure. All infrastructure. The roads budget is projected to dwarf other forms of public spending on infrastructure. The New Zealand government is now basically a road-building authority with bits tacked on. So, how did this happen? Pork barrel parochialism New Zealand is a regional democracy, and there’s a lot of pressure on governments to spread the love. Nelson, for example, hasn’t had a big central-government transport project in yonks. The first choice for a big transport project in Nelson, and the one preferred by the city’s mayor-king Nick Smith, was the Southern Link, a much-needed third arterial road into Nelson city. That project proved too controversial, with years of community protests, and eventually died in the environment court. To appease those sun-soaked top-of-the-southians, NZTA pivoted to an easier option: the Hope Bypass. Nowhere near as useful and almost as expensive, it’s a billion-dollar solution to a local road on the city’s suburban edge that gets a bit jammed up during peak times. It will supposedly enable further greenfield growth, but Richmond seems to have no trouble expanding suburban sprawl as it is. The people of Nelson don’t care, though. Nor should they. The costs are shared across all taxpayers, so there is little incentive for any regional centre to complain about the value for money. They’re getting a sweet new road. Politicians’ pipe dreams Chris Bishop has been dreaming of the Petone-to-Grenada link road since he was a wee lad. Growing up in the Hutt Valley, there was nothing he wanted more than to plough a great big hunk of concrete through the Korokoro hills. Petone-to-Grenada would be an objectively awesome project. Connecting the Hutt Valley to the southern side of Porirua would fundamentally reshape Wellington from a V to a triangle, making it a more cohesive city. The second stage, the Cross Valley Link, would create a more efficient east-west route across Lower Hutt, taking heavy traffic away from the Petone foreshore and allowing it to be a nice beachy area rather than a traffic-clogged hellscape. There’s just one problem: It’s really, really, really hard to build. The proposed route goes over steep hills, deep ravines, and would require two road tunnels with a combined length longer than the Mt Victoria tunnel. When it was last investigated in 2017, NZTA found the road would be vulnerable to major landslides in an earthquake, which negated a lot of the resilience benefits. Back then, the $955m price tag was deemed too much to be worth it. The estimates released this week put it at $2.1b to $2.6b. The thing is, Petone-to-Grenada may just turn out to be so good that it’s worth it. There’s a very real possibility that it massively overperforms its BCR. If Wellington grows to be a city of one million+ within the next 50 years, it will look like an amazing investment and one of the most impactful city-building projects in the country. And the area of Wellington that would benefit the most is Hutt South, Bishop’s electorate. The person who made that happen for the Hutt would be a legend. The Northland Corridor falls into the same bucket. A four-lane expressway connecting Auckland to Whangārei could be genuinely game-changing, opening up an underdeveloped region to new levels of productivity and growth. But it would also cost $22 billion, about the same as four City Rail Links. It would undoubtedly be a good road, but when you could build a rapid transit network in every major city in the country for the same price, is it worth it? No more low-hanging fruit It’s increasingly difficult to find major road projects with impressive benefit-to-cost ratios. In economic terms, that’s due to a concept called decreasing marginal utility. If two towns are only connected by a narrow horse track and you upgrade it to a basic road, you’ve added a huge amount of benefit for a relatively small cost. Every time you upgrade that road, you add a bit more benefit, but the amount of money you have to spend to get that benefit increases. There are still a handful of projects that can produce benefit-to-cost ratios in the double digits, but they’re mostly in overlooked and underinvested transport modes. A new cycleway or bus service is relatively cheap compared to an expressway, and when you’re starting from zero, any improvement is measurably significant. Roads, on the other hand, have never been neglected. Most of the obvious, easy wins have already been built, meaning the transport agency has had to reach deep into the reject pile to satisfy the government’s unquenchable demand for MOAR ROADS. Combine that with the rising costs of construction, and you have a recipe for bad investments. Hands in the slush fund NZTA, in theory, is meant to operate at arm’s length from politics. The transport minister sets a general direction for how they would like to spend the National Land Transport Fund, but is supposed to let the experts decide the projects and lead the design. In reality, ministers have effectively seized full control of the fund, allowing them to make ideological decisions to build projects that chase votes, appease donors, or block their opponents from building things they don’t like. The Roads of National Significance programme, introduced by the previous National government in 2009, gave the government justification to ignore the usual NZTA process and just build what they already wanted to build, regardless of how the investment case stacked up. The previous transport minister, Simeon Brown, took it a step further, imposing design guidelines that required all Roads of National Significance to be four-laned, grade-separated (meaning over- and underpasses rather than intersections) highways. That means even if NZTA found a cheaper way to build them, they are forced to take the gold-plated approach. That’s particularly relevant for the East-West Link to connect SH1 and SH20 in Auckland, which originally wasn’t going to be grade-separated except in a few instances. Even under the previous iteration, when it was estimated to cost $1.8b for 5.5km, Infrastructure New Zealand warned that it could be the most expensive roading project in the world on a per-kilometre basis. With the new specs, it’s estimated at $3.8b-$4.1b. Good ol’ gamesmanship There was a telling moment in the post-cabinet press conference when Luxon and Bishop were asked about criticism from Labour’s Tangi Utikere that the second Mt Victoria tunnel would be more difficult to build than the government anticipated. Bishop promised, “Within the next year, you will see spades in the ground on that project.” Luxon, meanwhile, went on the attack. “That’s a bit rich coming from Labour, isn’t it? These are the same clowns that cancelled Kāpiti to north of Levin in 2018, re-announced it in 2020, and didn’t do anything about it,” he said. He went on to criticise the previous government’s lack of progress on the Melling Interchange, Auckland Light Rail and Let’s Get Wellington Moving. “We’re getting on and doing it. Our legacy of actually getting stuff done is really important. No disrespect, but these guys have no ideas, no track record of delivery whatsoever. They can say whatever the hell they want but really, we’re not that interested.” It says something about the political calculus of transport spending. While nerds scream into the wind about benefit-to-cost ratios, for most voters the problem with transport projects isn’t that they cost too much relative to their value; it’s that they aren’t built at all. Voters punished the previous Labour government for the lack of progress on major works, and the National-led coalition is desperate to prove they’re different. That means there is little incentive for politicians to make smart, long-term investments and all the incentive in the world to ram through ill-advised, fast-tracked money pits. And if they don’t end up coming to fruition, they can always blame the next government for cancelling them.