After spectacular acts of violence, the hunt for suspects’ online trails — and the sources of their presumptive radicalization — often begins before a name has even been officially confirmed. Sometimes, as in the case of the 23-year-old mass shooter who targeted a Minneapolis Catholic school in August, posts provide evidence of nihilistic ideologies or other motivations (in that instance, an apparent idolization of other mass shooters and a desire to perform for aspiring ones). In other cases, such as that of alleged United Healthcare CEO assassin Luigi Mangione, the evidence is confounding, revealing an online profile that nobody would have found alarming, or even particularly interesting, before he handwrote a manifesto and pulled a trigger.

When conservative influencer Charlie Kirk was shot in the neck and killed in front of a gathered crowd at Utah Valley University — and soon a considerable portion of the social-media-using general public — the hunt for an online trail began almost immediately. Expectations were high for some sort of evidence, and not unreasonably so: Kirk was a divisive figure with a huge audience on social media; he was a comprehensively meme-ified man with predictable antagonists on the left and unlikely but organized enemies to his right; he was a figure with more than enough self-awareness to know who was angry at him, why, and how to make the most of it.

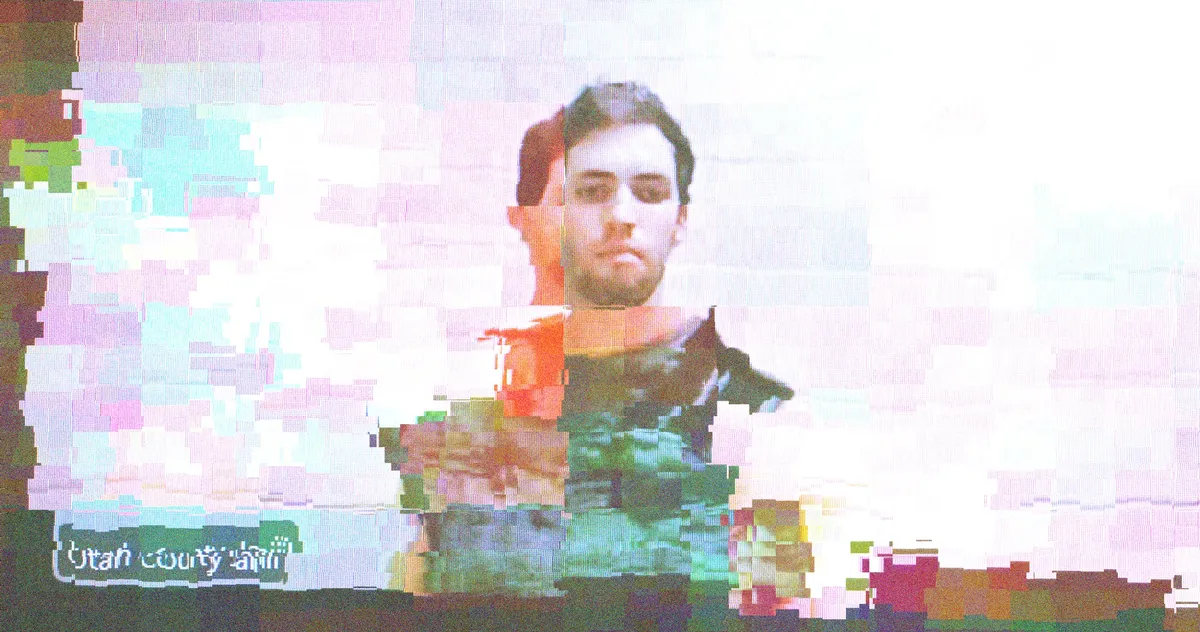

Before the suspect was named or apprehended, a rifle was recovered alongside shell casings engraved with messages including “Catch this, fascist!” but also a set of inscrutable memes; one reads, “If you Read This, You Are GAY Lmao,” while another is a reference to a popular video game. Once he was identified as 22-year-old Tyler Robinson, assumptions and theories, based on scraps of real and inauthentic online evidence, abounded about the suspect’s digital life: Was he a radical anti-fascist recruit? An irony-poisoned right-wing Groyper? Had he planned the shooting in some sort of chatroom, and did its members know what was coming? What had the internet done to this man and, by extension, to Charlie Kirk?

Internet-centric ideological theses — themselves clearly ideologically motivated — filled the brief void before more evidence emerged, and they have since mostly receded. Discord chat logs obtained by reporter Ken Klippenstein, combined with transcripts included in a subsequent charging document, suggest a range of possible motivations — hatred for Kirk, a relationship with a gender-nonconforming roommate, alienation from his own family (political or otherwise) — without revealing the existence of, as Elon Musk had claimed, some sort of online “terrorist cell.” Instead, these transcripts portray a group of friends who didn’t talk much about politics and who were shocked to find out what he had done. Robinson’s own account of the shell casings was less illuminating than it was, as peers described the alleged shooter himself, terminally online. “The fuckin messages are mostly a big meme,” he said. (In contrast, the suspect in a Colorado school shooting carried out the same day had posted extensively about mass murders and shared and consumed “white supremacist symbolism and neo-Nazi code phrases” on TikTok and X.)

Was Tyler Robinson radicalized online? To whatever extent it’s a meaningful, coherent question, the best answer we have, based on what little evidence we have — and with the expectation that more will be revealed in the coming days, weeks, and months — is: maybe? We don’t know. If and until we find out, though, the days since Kirk’s shooting have posed a related question: What about everyone else?

If the popular theory of online radicalization is that people lose touch with their humanity — or are merely driven to ideological extremity or total alienation — in insular, ideological accelerative communities, there were abundant examples of this phenomenon in the week following Kirk’s shooting. Seconds after Kirk was killed, a TikTok influencer streamed the scene mere feet away from the stage where it happened, frantically commanding viewers to subscribe to his channel as panicked bystanders screamed and fled. In the early stages of the manhunt, politically motivated users on X, and on forums like 4chan and Kiwi Farms, began constructing theories about how the shooter must have been trans and therefore predisposed to violence, laundering a preexisting shared obsession into the broader social-media conversation. Elsewhere on social media, defensive leftists convinced one another, with scant evidence and clear motivation, that Kirk must have been killed by a follower of far-right personality Nick Fuentes, who had feuded with him for years. (It seems like a version of this theory may have found its way to the writer’s room at Jimmy Kimmel Live!, drawing the attention of FCC chair Brendan Carr and leading ABC to take the show off the air “indefinitely.”)

Before and after Robinson was identified, a small but not insignificant number of people cheered Kirk’s death on public social-media channels, while right-wing internet users responded with an unprecedented mass doxxing campaign, collecting these posts and trying to get the people behind them fired, kicked out of school, or deported. This was all cheered on by the J.D. Vance — “call them out, and hell, call their employer,” the vice-president said while hosting Charlie Kirk’s show. It was gleefully justified as revenge for the left’s years of “cancel culture,” and was accordingly broad, sweeping up people who had merely criticized Kirk, as well as bystanders who had, in fact, said nothing at all. Elsewhere on social media, and especially on X, some users simply — and comfortably — called for direct retribution and declared that the time had come for a national divorce and civil war.

Animated, horrified, inspired, or merely unmoored into a state of disorientation by the shocking (and widely viewed) murder of a polarizing figure, a vast range of people revealed, on purpose or by accident, how alien to one another their normative experiences had become, online and off. Many surely wondered, from each edge of this nightmarish discourse — although perhaps not as much as people who didn’t enter the fray at all — in what world are people posting this stuff? In death as in life, Charlie Kirk has left a lot of Americans struggling to understand how their fellow citizens could possibly say or believe the things they do.

I don’t mean to suggest equivalence here. An obsessive, metrics-driven influencer is a freakish cautionary tale, not a militant slipping into terroristic threats. You might question the character or judgment of someone who publicly celebrates the death of public figure they hate, or vents crudely or angrily about their political opponents after seeing a video of the murder of an online personality they love or identify with, but they’re not participating in an organized online campaign, supported by elected officials, to have their enemies “thrown from civil society,” kicked out of school, fired from their jobs, or stripped of their driver’s licenses.

Fearful elected Democrats have been far more careful than scattered liberals and leftists on social media, retreating to platitudes about how violence is bad and speech should never be met with violence, and have been harshly censured by Republicans in cases where they offered anything but praise for Kirk, as in the case of representative Ilhan Omar — the right is, as usual, more aligned. The president claimed that the “radical left” was “directly responsible” for an act of “terrorism” and pledged to go after people and organizations that “contributed to this atrocity and to other political violence.” His closest adviser, Stephen Miller, was more direct and spoke in the same voice as the burn-it-all-down contingent of Kirk’s online fandom. Kirk’s death was the result of “a vast domestic-terror movement,” he told Vance on Kirk’s show, before promising to use “every resource we have at the Department of Justice, Homeland Security, and throughout this government to identify, disrupt, dismantle, and destroy these networks and make America safe again for the American people.”

What the disparate range of alarming, distasteful, and bizarre posts from non-politicians following Kirk’s death do have in common is that they don’t represent widespread American views of political violence — survey after survey shows little appetite for it across parties. They were also made from the blinkered contexts of personalized feeds, or from within insular online communities, where such statements may have gradually become normal and the prospect that someone might find them objectionable — or find a way to use them against you — has been forgotten. This is despite the fact that they’re very much still speaking in public, or at least vulnerable to subject to surveillance by fellow users who might hate them. (This might be the only meaningful way in which “filter bubbles” turned out to be real.)

These kinds of posts, made from any ideological perspective, have another trait in common: If they ever turned up in the course of some future online sleuthing, they’d be understood and portrayed as incriminating, total proof of motive and radicalization. If a theoretical suspect were revealed to have written comments like “America became greater today” after Kirk’s assassination, the story, true or not, would be that they’d been indoctrinated online in plain sight (the South Carolina teacher who actually posted that message on Facebook has since been fired). If one had posted something along the lines of “the Democrat party is a domestic terrorist organization” with “demonic trans foot soldiers” that must be “stopped,” the narrative would be likewise settled among liberals: That’s a guy who was steeped in online radicalism on X. (That one is actually a post from a prominent conservative news publisher.)

Of course, we don’t really expect the many thousands of people saying this kind of stuff about the killing of a widely beloved and despised famous person to one day resort to violence. We understand them as downstream not just from a specific event and its fallout but from a terrifying and heavily politicized decline in Americans’ trust and regard for one another. (Also, it should be said, as relatively rare public expressions of private sentiments more people might confide to friends or family, who are more likely to agree, understand, or simply feel comfortable knowing that they don’t mean much.)

This should give us pause about the ritual of assigning such posts so much value in cases where violence actually occurs. As a general theory explaining the ills of the world, “online radicalization” is a comforting fiction without predictive power, a way to contain shocking events with complicated, overlapping motivations inside arbitrary digital boundaries, a tempting method for dismissing deeper and more sinister problems as mere symptoms of a vague and external online menace, and as a tool for political blame or vindication. “The internet” can usually no more provide us with the full story of why someone decided to kill another person than their isolated experiences at work, school, or home, which we hardly struggle to see as entwined and inseparable. But the grim incentives and cynical priorities of the commercial platforms that make it up might help explain how we come to see one another as irredeemable.