This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with The Salt Lake Tribune.

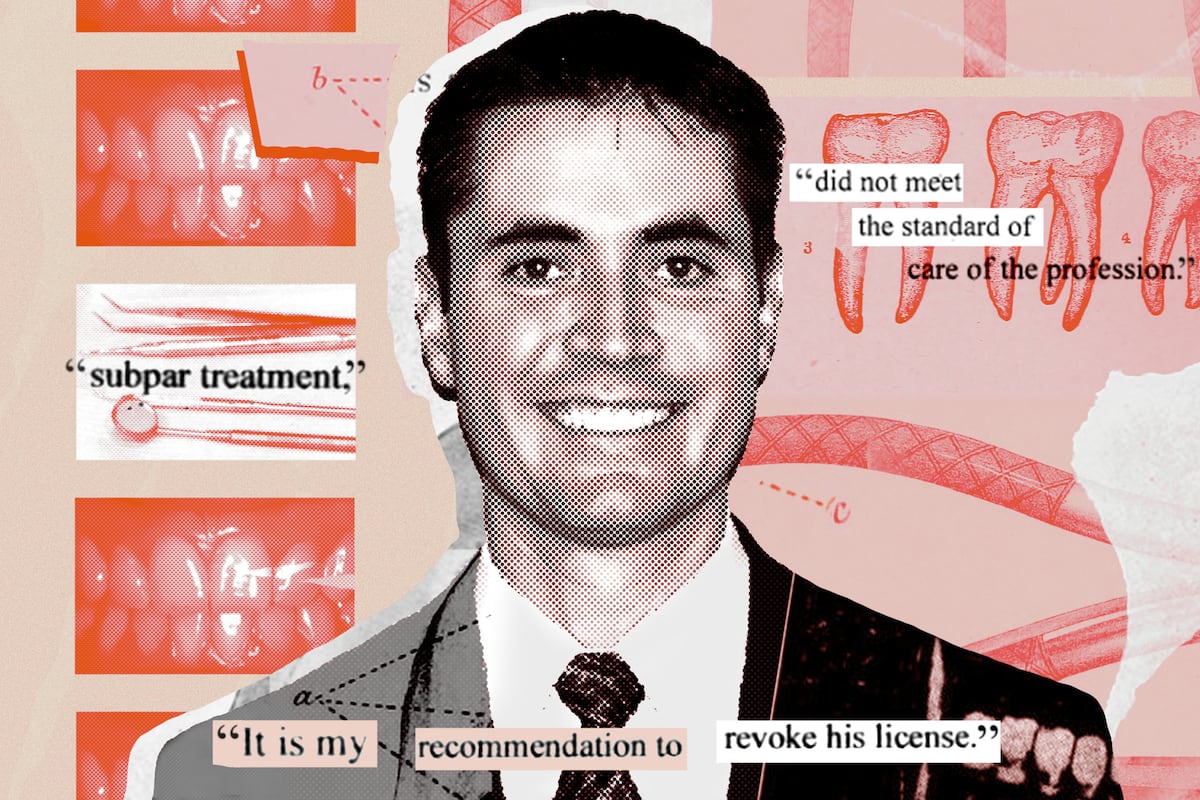

The patients kept coming to the Utah oral surgeon’s office — one after another, year after year — with dental work that the surgeon said had gone wrong. He later recounted in a letter to state licensors that he had seen dental implants that had been the wrong size, patients with chronic sinus infections and one person whose implant had become lost inside their sinus cavity. These patients, he said, had all been worked on by the same dentist: Nicholas LaFeber.

The surgeon, a 30-year veteran, wrote the letter in November 2022 after Utah’s licensing division asked for his opinion of work done by LaFeber, whose license was on probation after the agency determined he had provided substandard care to more than a dozen patients.

His warning was blunt: He believed LaFeber wouldn’t improve as a dentist and should not be performing dental implant procedures. He had seen LaFeber make the same mistakes in patients for years, he wrote, causing “severe” and sometimes life-changing complications.

“I believe that he is not competent to place implants,” the oral surgeon, Creed Haymond, concluded. “I give this opinion with soberness and sadness, but I feel I have a duty to aid the board in protecting the public from what appears to be an incompetent practitioner.”

His assessment of LaFeber’s skills in restorative dentistry was also mentioned in a February 2023 order regarding agency action on LaFeber’s license. Haymond did not respond to interview requests.

This was the second letter that Utah’s Division of Professional Licensing had received recommending that LaFeber be stopped or limited from practicing after more than a decade of dentistry in Utah, according to records obtained by The Salt Lake Tribune and ProPublica. The agency licenses Utah dentists and other professionals and investigates allegations of misconduct.

Two years prior, another dentist who had considered buying one of LaFeber’s practices recommended LaFeber’s license be revoked after looking through patient files: “As I started going through charts, as well as seeing the previous work, I began to realize how poor he treated these individuals,” wrote Brandon McKee. “Patients with failed implants are put on antibiotics and told to wait while the implant is continuing to heal. Some of these are for nine months.”

This letter was discussed in a September 2020 public dentistry board meeting. McKee did not respond to interview requests.

The licensing division’s dentistry board — whose members are mostly dentists and hygienists — recommended to Utah licensing director Mark Steinagel in December 2022 that LaFeber’s license be revoked after reviewing additional evidence suggesting his skills had not improved.

But despite this recommendation and the letters of warning from his colleagues, Steinagel reinstated LaFeber’s license in May 2023 after the dentist completed three years of probation, which included taking remedial classes.

Since LaFeber’s license was reinstated, new patients say they’ve been hurt. The Tribune and ProPublica spoke with two patients who say they saw the dentist within the last year for what they believed would be routine cavity fillings. Instead, they say they left in pain that became prolonged and ultimately required the procedures to be redone by other dentists. Neither knew when they sought dental care that LaFeber had nearly lost his license after regulators determined his work fell below the standard of care.

“I had never had this done before, so I didn’t know what’s normal,” said one patient, Michelle Lipsey. “I was just like, ‘He’s an adult, male dentist. He probably knows what he’s doing.’”

Lipsey filed a complaint against LaFeber with licensors in July detailing her experience, but the agency closed the case a month later and took no disciplinary action.

LaFeber said he would not discuss individual patients because they did not grant him permission to do so. He told The Tribune and ProPublica that he has always tried to keep his patients’ best interests in mind. “I had a few outcomes from dental work that had complications and needed further treatment,” he wrote in an email in response to questions.

“I assume every dentist encounters some percentage of negative patient outcomes and I have no reason to believe that my practice had a higher percentage than others.”

Melanie Hall, a spokesperson for Steinagel and the Division of Professional Licensing, said in response to questions that the division only revokes someone’s license when their conduct has been “especially egregious” because doing so “ends a career.”

The agency’s top priority, she said, is keeping Utahns safe — but she added that it also wants to ensure that licensees have a chance at “professional rehabilitation” and, when appropriate, can continue to work and earn money.

The state has revoked two dental licenses since June 2015, according to a Tribune and ProPublica examination of a decade’s worth of publicly available licensing division records.

Hall said that LaFeber’s license was reinstated despite the dental board’s recommendation because the dentist had finished the remedial courses that the board required him to take and his probationary period was ending. She noted that no other patients filed a complaint during that three-year period and that the dental board’s role was to only make recommendations to Steinagel and his staff.

That decision bothered some of those who served on the dental board during that time. Two former board members told The Tribune and ProPublica that they were frustrated state licensing division leaders did not listen to them and that they felt LaFeber should not practice dentistry given his record. Both spoke on the condition of anonymity because of potential professional repercussions.

“You hate to take somebody’s livelihood away from them when they’ve gone through years of dental school and had a practice,” one of the former board members said. “But the board’s job is to protect the public.”

In LaFeber’s case, the former board member said, “the public was not well-served.”

LaFeber, without knowing the identities of the board members, suggested that some might have been biased against him.

‘Every one of these cases was alarming’

LaFeber said in public dentistry board meetings that he came to the attention of the licensing division in late 2019 after one of his former employees filed a complaint. He said the employee, who he said he had previously fired, directed licensors to more than a dozen cases in which he admitted during a board meeting that he had provided “poor patient care.”

State licensing officials could have suspended or revoked LaFeber’s license, but instead, in early 2020, they struck an agreement with LaFeber — a common outcome in license discipline cases. According to the agreement, investigators found that some of the patients in those cases had had root canals that resulted in infections or needed to be redone.

Licensors also determined that LaFeber had improperly placed permanent replacement teeth in other patients, including one whose implant extended into the sinus cavity, the document said.

LaFeber agreed to spend three years on professional probation, during which he would be under the supervision of another dentist whose time he was required to pay for. He was still allowed to perform dental work during that period, according to the stipulation, but agreed not to do implant procedures or root canals.

He was not required to tell his current or future patients about this discipline. Like most other states, Utah has no law requiring patient disclosure when a licensed professional is disciplined, and a review of more than 3,200 filings from the licensing division’s website shows the state has rarely required disclosure of unprofessional conduct to patients.

The Utah regulators who discipline licensed professionals act only when someone files a complaint, like what happened in LaFeber’s case. “We don’t have manpower or staffing for proactive investigations,” Larry Marx, the state’s health care licensing bureau manager, explained to the dental board in a 2020 public meeting.

Once LaFeber was on probation, oversight of his progress moved to the dental board, an advisory group whose role it is to interview probationers in quarterly public meetings and make recommendations to Steinagel about whether the professionals completed their probation and if they should have their licenses reinstated.

In these interviews with the dental board, LaFeber admitted his mistakes. He blamed bad outcomes on being burned out from owning four dental clinics, and he said he had done procedures on friends and acquaintances who actually needed more specialized care but didn’t have the money.

“Some of it I will just admit was a poor, poor choice on my part,” he told the board, according to a recording of the meeting. “And I can also say for some of them, they are very dear friends of mine, that I have either coached their kids or helped them in Scouts or something else, single moms, and trying to help them out.”

In addition to the problems that the former employee initially reported to the state licensing division, one dental board member, Ruedi Tillmann, looked at more than a dozen other files of LaFeber’s during the first few months of his probation and found other cases in which Tillmann saw indications that patients had poor outcomes, according to a December 2020 board meeting.

Tillmann, a dentist, said during the online meeting that he saw “a number of cases” where LaFeber did four or five implants on a single patient and none of them properly integrated into the patient’s jawbone. “Poor margins, open margins, implant crowns not sitting on implants correctly,” he said about patient files he reviewed. “I’m sorry to be harsh. It’s just that every one of these cases was alarming to me.”

Daniel Poulson, another dentist on the board, questioned why LaFeber would do substandard work on his patients, including people he said he knew and cared about.

“With 30 cases, what that communicates to me is you didn’t learn. You just kept doing it,” Poulson said during the same meeting. “And to blame that on being stressed or overworked — we’re all stressed. Dentistry is an incredibly stressful profession. But that shouldn’t, in my mind, make an excuse for ill-treating a patient. Using a lot of antibiotics to cover infections that last years is just out of bounds.”

LaFeber told the board during this meeting that he was confident he could improve his dentistry by taking continuing education courses and by being more selective about patients and referring them more often to specialists instead of trying to do the work himself.

He also downsized to just one clinic, Sandy Center Dental, a wood-trimmed office suite in a large, tan stucco building located in a Salt Lake City suburb at the base of the Wasatch Mountains.

‘They were so disgusted with all the problems’

LaFeber met with the dental board 11 times during his probation in public meetings that were often conducted on video calls because of the coronavirus pandemic. He was cheerful and agreeable during meetings, even at times when board members asked him pointed, critical questions about his work.

His polite nature was noted several times in records reviewed by The Tribune and ProPublica. For example, McKee, the dentist who had considered buying LaFeber’s practice, wrote in his letter to the board that LaFeber came across as a “humble,” “very nice guy” who patients trusted. A dentist who leads a dental examination agency wrote in his summary of an exam that LaFeber took that he was “overly pleasant to the extreme.”

Members of the dental board remarked during public meetings about how “unique” LaFeber’s case was, and they questioned what the right metric would be to determine whether his dentistry had improved and he was safe to work with patients.

Utah licensors rarely discipline dentists over whether they are competent to do their jobs, an analysis by The Tribune and ProPublica found. A review of disciplinary records from the last decade shows dentists most often getting in trouble for drug or alcohol use or for overprescribing or diverting prescriptions.

Hall, the licensing division spokesperson, said the agency does not track how many standard-of-care complaints it receives, but acknowledged that proving those types of cases tends to be difficult.

“As a result, they are less likely to lead to disciplinary actions compared to cases involving drug use, unlawful behavior, or practicing outside one’s scope of practice,” she said.

But tension was growing between LaFeber and the dental board: While LaFeber had taken a few online, self-paced courses, board members felt he needed more intensive, hands-on classes to improve.

A breaking point between LaFeber and the board occurred near the end of LaFeber’s probation. At the December 2022 dental board meeting, LaFeber peppered members with questions about the board’s role governing probationers and implied that a board member had acted improperly by soliciting complaints about him.

The board seemed equally frustrated; LaFeber still hadn’t enrolled in the hands-on courses they had required him to take, programs that could have cost up to $50,000. LaFeber had instead taken a licensure exam and failed several sections, according to a copy of the exam results obtained by The Tribune and ProPublica, which was also referenced in the 2023 agency order.

LaFeber did not respond on the record to questions about these test results.

Given the test results, Poulson, who had become board chair, said in the public meeting that he worried whether LaFeber would be able to practice dentistry safely by the following February, when his probation period would end.

“I have two doctors that once tried to buy your practice. They gave it back because they were so disgusted with all the problems they were having with patients,” Tillmann, one of the board members, said in that same meeting, recalling previous conversations he had.

Poulson suggested that the group make a motion recommending that the state licensing division either revoke or suspend LaFeber’s license, saying that the action would be “protecting the public from inferior care.” The board unanimously voted to recommend revocation.

A few months later, Marx issued the agency order stating that LaFeber’s license should be suspended until he could demonstrate he could practice dentistry “with reasonable skill and safety.”

LaFeber, though, had one more chance to respond before the suspension would take effect. Soon after the agency order, LaFeber enrolled in and completed his remedial training. He also hired an attorney who signaled his intent to fight the agency’s action, according to public records.

In response, Marx requested that the agency’s move to suspend LaFeber’s license be dismissed, noting that LaFeber said he had delayed complying with the dental board’s requirement that he complete further training because of “financial limitations.” Then, Steinagel reinstated LaFeber’s license.

By this point, Steinagel’s agency knew not only about the reports of patients with improper tooth implants and the failed root canals that led to LaFeber’s probation, it also knew the state dental board had recommended that LaFeber’s license be revoked.

In addition, the agency was aware LaFeber had been sued three times for medical malpractice — including by a patient who alleged he had implants placed in his sinuses, which caused sepsis, and another patient who said in her lawsuit that, after months of painful infections, she went to another dentist who found a broken dental instrument lodged in her gums. (LaFeber told The Tribune and ProPublica these lawsuits were settled by his medical malpractice insurance carrier and there was never any determination made that his treatment fell below the standard of care.)

LaFeber said in response to questions that he was not aware of any recommendation from the board to revoke his license — though according to recordings and minutes of the public dentistry board meetings, he was present when the dentistry board took its vote. The board’s revocation recommendation is also referenced in the agency order he received, which The Tribune and ProPublica obtained through a public records request.

The dentist said he felt he was treated fairly by licensors and most members of the dentistry board, but added that he felt one board member did not disclose a conflict of interest and had a “personal vendetta” against him. LaFeber did not respond on the record to follow-up questions asking for further details. He said he complied with every request by licensors and its dentistry board and “even went above and beyond” by taking additional continuing education. He noted that he passed the remediation courses and related tests that the board had requested.

“I also worked with a supervising dentist, at significant expense, who reviewed my work and provided mentoring for 3 years between 2020 and 2023,” LaFeber wrote.

After taking these courses, he said, he has been able to incorporate new technology in his practices that has improved patient outcomes. “Dentistry is an area that is constantly evolving with so much new technology,” he said, “and I welcome all information sources that can help me improve my practice.”

The Tribune and ProPublica asked the two former board members who spoke to the news organizations whether their vote to recommend LaFeber’s license be revoked would have changed if they had the opportunity to weigh in again after he had completed his remedial training.

One former board member said they didn’t think the training completed to satisfy the state was enough to overcome years of poor dentistry. Another said that nothing seems to have changed given new patient complaints. Three board members who were involved in LaFeber’s case declined to comment for this story, and four others could not be reached.

New patients say they were harmed

With his license restored, LaFeber started to once again grow his business. Public records show he still owns Sandy Center Dental, and in July 2024 he got a business license for a second clinic about 10 miles to the west. (An online ad this summer indicated LaFeber was trying to sell his second practice.)

LaFeber is referenced as the sole dentist on websites for both of these businesses. In his response to The Tribune and ProPublica, he said he owns and operates a single office, Sandy Center Dental, where he works four days a week. A Sept. 23 search of public business records show he is still listed as the registered agent and principal for both practices.

LaFeber said he helped start the second office, Parkway Smile Center, but said it is now “entirely owned and managed by another dentist.” The new owner could not be reached for comment.

In the nearly two years since LaFeber’s full return to practice, at least two more patients have publicly complained they were harmed under his care, both of whom The Tribune and ProPublica contacted after they left negative online reviews.

Michelle Lipsey had been a patient at Sandy Center Dental for nearly eight years, but she said in an interview that she hadn’t been to the dentist for a couple years after her second child was born. She said LaFeber told her during an October 2024 appointment that she needed five cavities filled. She returned a week later for the procedures.

For weeks after, Lipsey was in pain, and she returned to Sandy Center Dental later that month, complaining that she couldn’t sleep and was only able to eat soft food, according to her medical records. LaFeber redid some of the fillings, medical records show, but Lipsey said the pain persisted. She said a second dentist told her that LaFeber hadn’t properly sealed the fillings and had drilled far deeper than he needed to.

LaFeber noted in her medical records that he tried to call and text Lipsey after she left a negative review online. “Remember patient was very nervous,” her patient file reads. “We tried our best to help calm but at no point had the appointment gone as she described in the post.”

Haley Stafford described a similar experience earlier this year. She said that, based on what LeFeber told her, she was expecting to have two cavities filled during a March appointment; instead, he put fillings in seven teeth. She recalled in an interview that his hands shook when he gave her numbing shots. (The testing exam results reviewed by The Tribune and ProPublica also noted LaFeber’s unsteady hands.)

“That was the first time he actually did work on me,” she said. “And it was completely botched.”

She’s been in near-daily pain since, she said, and has needed more dental work on her affected teeth, including two root canals. Stafford found a new dentist, but the repair work has cost her thousands of dollars.

Both Stafford and Lipsey said LaFeber contacted them about refunding their money.

LaFeber said he doesn’t recall refunding money to any patients after a complaint. He said he could not comment on specific cases to protect patient privacy, but said that sensitivity and pain can happen after a treatment.

“We try to do all we can to minimize it,” he said. “The presence of pain does not demonstrate treatment that fell below the standard of care.”

Lipsey filed a complaint with licensors in late July and said she was interviewed by an investigator and shared X-rays from before and after LaFeber filled her cavities.

Licensors sent Lipsey an email in late August saying that they were closing the case and that “appropriate action was taken,” according to a screenshot of the email Lipsey shared with The Tribune and ProPublica. They would not tell her what that action was, saying the investigative record was considered private under Utah law. Licensing officials declined to comment on the outcome of Lipsey’s complaint.

If licensors had disciplined LaFeber, it would be considered a public record. The agency has the option to address a complaint informally by giving a verbal warning to a licensed professional or writing a letter of concern. Those measures typically are not disclosed to the public.

LaFeber told The Tribune and ProPublica that Lipsey’s complaint was dismissed and he did not receive any warnings or a letter of concern. Licensors “investigated it thoroughly and found it to be meritless,” he said.

LaFeber’s license remains in good standing, according to the state’s licensing database in September.

Stafford hasn’t filed a complaint with the state and said she had no idea LaFeber had nearly lost his license until a reporter reached out to her.

How does a dentist nearly “lose their license and get it back,” she asked, “and patients are not aware of that?”