Copyright Inside Climate News

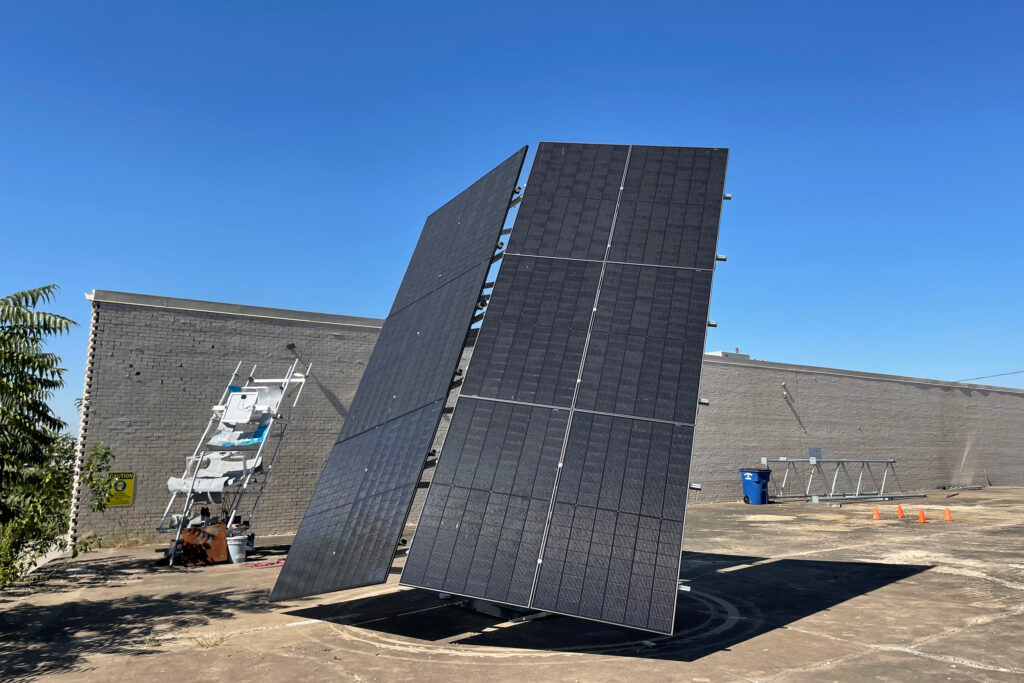

DALLAS—Texas has more solar power than anywhere else in the U.S. But there’s plenty of opposition to the energy resource that’s credited with helping avoid the risk of summer blackouts this year. Chief among these criticisms is the issue of land. More often than not, roofs and lots end up often being finite spaces. For installers, home owners or developers, ensuring there’s enough room for the number of solar panels needed can be an obstacle. A new Dallas-based start-up, Janta Power, aims to address that. The firm created 3-D solar towers—modular panel designs that swivel on a single axis to track the sun and are vertical rather than horizontal. Janta’s founder, Mohammed Njie, said that by building up, the towers reduce land requirements, installation time and maintenance complexity, while delivering higher energy output. The company reports that the towers allow for three times more capacity per acre and produce 50 percent more energy than conventional flat solar panel arrays, and 25 percent more power than those that track the sun. Earlier this month, the start-up announced it raised $5.5 million in seed funding. The financing round was led by MaC Venture Capital. Its managing general partner, Marlon Nichols, said that with the rapid growth of artificial intelligence creating strain on the grid, traditional solar isn’t efficient enough and demands too much space, Nichols said. “Janta is different,” the managing partner said. “Their towers deliver three times the efficiency in a fraction of the footprint, making solar viable where it wasn’t before.” The money will be used to continue developing towers and to build out the 10-person company, as the firm looks to hire a vice president of sales, supply chain leader, senior mechanical engineer and a software engineer. As of now, everyone wears multiple hats. The company’s finance officer also looks after operations, human resources and other administrative work. In May, Janta was selected as the sustainable aviation winner of the Airports for Innovation program and will partner with Munich International Airport, Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport and the Spanish airport operator Aena to pilot its vertical solar technology. Using Janta Power’s vertical towers will expand renewable energy generation on airport grounds, said Munich Airport Chief Commercial Officer Jan-Henrik Andersson. It’ll also support the German airport’s commitment to achieving net-zero emissions by 2035. Janta’s clients, like airports, can make aesthetic additions to the sides of the towers with aluminum or polycarbonate, for a sleeker look or space for logos. As Texas produces one quarter of the country’s energy and more than 12 percent of U.S. electricity, its infrastructure becomes part of the scenery of day-to-day life. Nodding pumpjacks are a famed part of the Texas landscape—a slow moving vision of the state’s history and oil industry. But a genuine concern about new solar projects, whether in rural areas or not, is how the rows and rows of photovoltaic panels alter the feel of a place. It’s a point of tension about solar energy that Njie knew he had to address from the start. “Some [customers] are concerned about how panels look,” he said. “It has to look good.” Janta has built about 10 systems so far, with towers as small as one kilowatt and as large as 10 kilowatts. A 5-kilowatt system, for example, stands 17 feet tall. Depending on the location, the panels are spaced 10 to 20 feet apart to avoid shading. They also have what the company calls a “smart box,” a separate compartment where the microcontroller and other connections are housed. In some scenarios, the smart box goes inside the tower or somewhere nearby. The company sources its solar panels from Canadian Solar and QCells, a South Korean company with a U.S. manufacturing plant. Janta is looking into buying panels from Texas-based solar manufacturers as well. The start-up manufactures its steel structures in Texas and has wind ratings determined by the location of the tower. In Dallas, the solar towers are rated for at least 110 miles per hour winds, while in Houston, the rating needs to be for at least 140 miles per hour, Njie said. While the firm’s target markets are commercial customers, like airports, schools, hospitals and data centers, it has also been fielding interest from residential and utility customers, Njie said. Part of the reason for what he says is increasing demand is because Janta’s vertical solar towers have two summer peaks instead of one, the founder said. Typical solar applications peak in energy production around midday, leaving customers and grid operators to switch to other fuel types and use batteries in the early mornings and evenings. But because of the steep angle of the panels in Janta’s towers, the systems produce the most power in the morning and then again in the afternoon. Njie said the idea for going vertical came to him after years of contemplating how to keep the lights on. Growing up in The Gambia, he became accustomed to the dreaded sound of the power clicking off before everything went dark. In the small West African country, unreliable electricity is widespread among the half of the population that can access it at all, Njie said. Most rural areas aren’t reached by the grid and have no access to electricity, and the state-owned utility relies exclusively on expensive imported fossil fuels that leave urban areas with high tariff costs and frequent blackouts. It was particularly frustrating as a kid, Njie, 30, said. The power seemingly always went out while he was playing a video game or halfway through his homework. But he reckoned that, given that he had power at all, he was among the fortunate ones. By high school, his exasperation grew. He couldn’t stand that electricity wasn’t available to areas not far from his home. He wanted to solve that problem in a renewable, sustainable and reliable way. So he decided to study electrical engineering. He enrolled at Southern Methodist University, where his brother had earned his master’s of business administration, and immediately sought out the Hunt Institute for Engineering and Humanity, where he was hired as a student researcher. Njie was trying to figure out how to solve the issue of electricity access in The Gambia. During winter break of his freshman year in 2019, he partnered with the Hunt Institute to return to The Gambia to meet with government officials and rural villagers to test different methods of how to deliver reliable electricity. On that trip, a team visited a primary and secondary school outside of the capital city of Banjul that agreed to be a beta test for an early vision of Janta’s solar panels, designed to bring clean, reliable energy to the country. The school was built in 2011 and had never had electricity before. They installed solar panels, batteries and a solar charge controller. A few months later, the school administrators reported that electricity had allowed the school to introduce fans, lights and install computers for both the students and the teachers. “It just creates this really awesome impact,” Njie said. “They don’t have to go home right at five o’clock, they can stay later because there’ll be electricity where they can turn on lights,” Njie said. As he was sorting out how to increase the capacity for the school, one of the issues was that the school might not have enough space to produce all the power they could need going forward. How could he capture as much sunlight as possible while using as little land? He found a solution right before his eyes in nature and society—in trees and skyscrapers. The trees which consume the most sunlight are tall pillars, using little ground space in comparison to how much energy they’re consuming. And society had already solved this land use issue through tall buildings. “One of the things I thought about is: Can we do it with our energy technology?” Njie said. “The answer is: absolutely.” In five years, Janta hopes to have saved tens of thousands of acres of land compared with what would be used if customers relied on traditional solar installations. Njie also hopes to lower the cost of electricity across the world, by expanding the company beyond the United States. But Njie knows it’s not going to be easy. The firm’s warehouse space has relics of previous iterations. He and his co-workers tried using concentrated solar — reflectors and lenses to generate heat. But these technologies were a lot more expensive and had too many moving parts. At the mostly windowless industrial workspace in Dallas’ Design District, they now do small scale prototypes, piloting and testing. It’s an environment suited for a startup. A series of sit-stand desks run along one wall, each workspace crowded with multiple screens. One has a red camping chair facing it. Anchoring the 3-D printers and automated cutting machinery in the brick and cement warehouse is a pickle ball net. They used to play more often and have friendly competitions. But it became less fun, Njie said, when he always won. By using one of their own towers onsite, they’ve been able to nix a significant portion of their office’s electricity bill. Before, their bill routinely ran upwards of $1,000 a month. Now, it hovers between $200 and $500, depending on the month. They’re going to add batteries to the tower so they can use more of the excess energy they’re producing. While it’s technically a pilot model, the tower is interconnected with Texas’ grid and exports the leftover energy they can’t use. The smart box is located 10 feet away, inside the warehouse, near the intern’s desk.