By Adam Woodward

Copyright euroweeklynews

In a new controversial move to combat rising obesity, the UK government has introduced regulations that restrict Coca-Cola refills at popular dining establishments like Nando’s, limiting diners to just one glass of full-sugar fizzy drinks per meal.

The policy, which became effective on October 1, marks the latest in a series of interventions aimed at curbing sugar consumption, sparking debates over whether such measures represent essential public health safeguards or unwelcome government overreach into everyday dining habits.

How the UK Government plans to restrict Coca-Cola indulgences at Nando’s

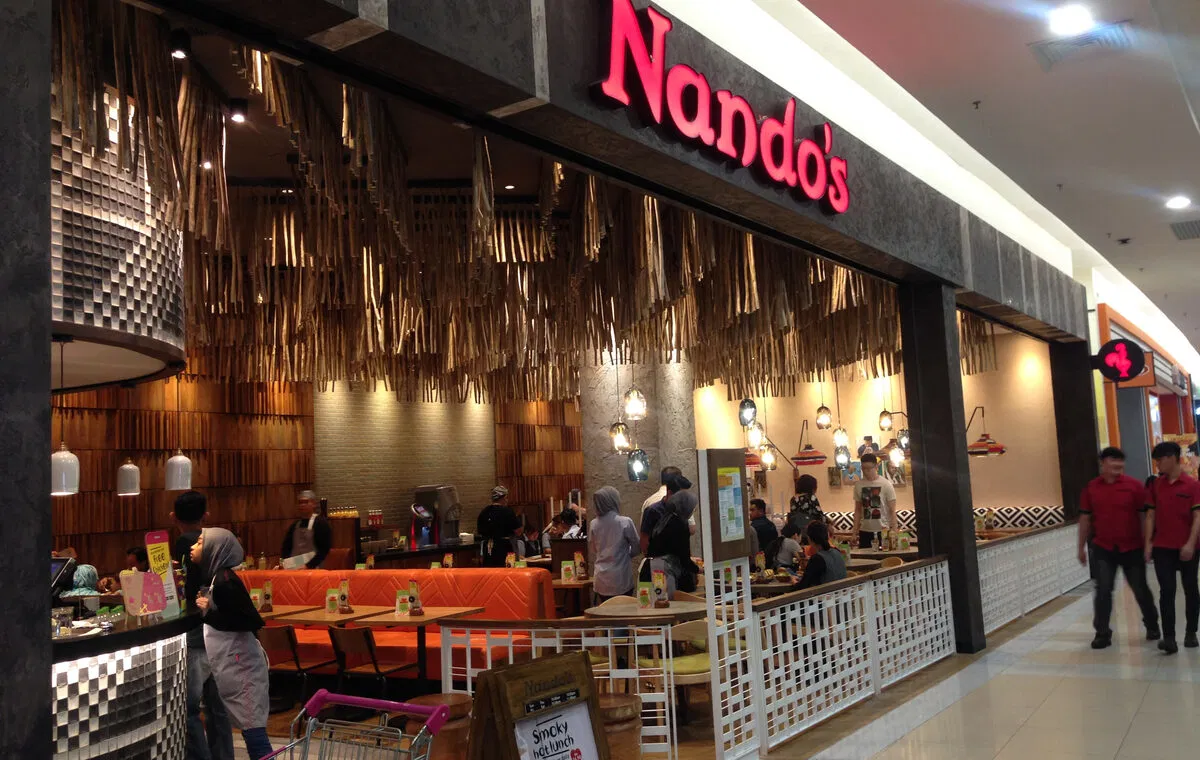

Customers at Nando’s, the peri-peri chicken chain famous for its bottomless soft drink refills, are now greeted with a stark new reality: full-sugar Coca-Cola is off-limits for unlimited pours. Social media photos circulating online reveal stickers plastered on drink dispensers, bluntly stating: “Want Coca-Cola Classic? It’s one glass only. Based on new government laws, we’ve had to limit Coca-Cola Classic to one glass per customer. Still thirsty? Help yourself to one of our low-sugar fizzy bottomless soft drinks.” Low- and zero-sugar alternatives like Sprite Zero and Fanta Zero are still freely refillable, preserving some choice in the clampdown.

Nando’s has confirmed it is fully complying with the mandate, which applies across the hospitality sector. A spokesperson for UKHospitality, the industry’s trade body, stressed, “From 1 October, hospitality businesses will be complying with new regulations that have introduced a ban on free refills of sugar-sweetened drinks in hospitality. Venues work hard to ensure that customers have a wide range of drink options to choose from when they visit our sector and will continue to ensure that is the case.” The move ends a long-standing perk that allowed unlimited refills of sugary sodas, a staple of casual dining that many patrons had come to expect.

The UK government expands its push to restrict Coca-Cola and junk food promotions nationwide.

The Coca-Cola restrictions are just one front in a wider UK government offensive against unhealthy eating. From this month on, “buy one, get one free” deals on junk food in supermarkets, high- street shops, and online retailers are banned in England, a rule designed to make it harder for shoppers to stock up on high-sugar or high-fat items. Free refill promotions for sugar-laden drinks in cafes and restaurants fall under the same prohibition, while a ban on junk food advertising before 9pm on TV is planned to launch in January.

To enforce these rules, the government has rolled out a classification system labelling “unhealthy” products: full-fat colas like Coca-Cola qualify due to their sugar content, joining the ranks of crisps, chocolate, ice cream, cakes, fish fingers, and even certain pizzas that are high in fat or sugar. The measures build on efforts from both Conservative and Labour administrations, reflecting a cross-party consensus on tackling dietary excesses.

The obesity epidemic inspired the UK government’s drive to restrict Coca-Cola and others.

At the heart of the policies lies a severe public health crisis. NHS data reveals that around one in four UK adults and one in five children aged 10 to 11 are living with obesity, which could lead to risks of type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and certain cancers. The toll on the health service is staggering, with obesity-related costs exceeding £11 billion annually.

Proponents, including the Department of Health and Social Care, hail the reforms as game-changers. A spokesperson said: “Obesity robs children of the best possible start in life, sets them up for a lifetime of health problems and costs the NHS billions.” They hope the advertising ban alone could avert 20,000 cases of childhood obesity, while the promotion restrictions promise £2 billion in health benefits and £180 million in NHS savings over 25 years from retail curbs, ballooning to £57 billion and £4 billion from hospitality limits. Evidence provided by officials shows price promotions heavily sway purchases, especially among children, justifying the intervention.

Yet, as the UK government tightens its grip on Coca-Cola and similar vices, critics are sounding alarms over what they call an ever-creeping nanny state. Diners and industry voices decry the rules as government overreach, arguing that personal responsibility, not bureaucratic edicts, should guide dietary decisions. With bottomless refills now a relic and supermarket bargains curtailed, many wonder if the state has gone too far in policing plates and palates. Should the government be meddling in our dietary choices at all?