Copyright independent

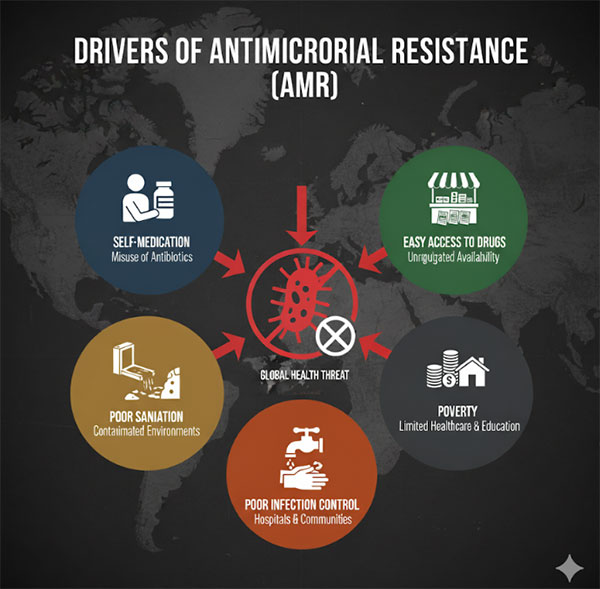

In the first of a two-part series, experts warn that without urgent action, drug-resistant infections could cause millions of deaths per year NEWS FEATURE | IAN KATUSIIME | A narrow path glides through the slum of Katanga giving visitors a fleeting rhythm of the decades-long settlement that lies between the valley of two iconic landmarks in Kampala: Makerere University and Mulago National Referral Hospital. A ride through this path on a boda boda is a glimpse into the deepening economic divide that is inescapable in the Ugandan capital. Shanty houses next to each other, tiny shops selling household items, residents gazing at passers by, women preparing meals and light conversations going on define a typical day here. At the end of the narrow walkway about 100 metres lies a drainage channel with filthy water and mounds of rubbish piled onto each other. Children aged about 8 and below mill around the channel oblivious of the health complications it poses. With dense housing, limited sanitation, the Katanga slum has become fertile ground for one of Uganda’s most insidious public-health challenges: antimicrobial resistance (AMR). This occurs when microorganisms like bacteria, viruses, and fungi become resistant to drugs designed to kill them, such as antibiotics. “In the urban slums, there is a lot of crowding so the spread of AMR can be enhanced for example multi-drug resistant TB. Imagine what can happen where six people sleep in one room and there is no compartmentalisation,” says Dr Andrew Kambugu, Executive Director of Infectious Diseases Institute, in an interview with The Independent. Anti-microbial resistance is one of the core areas of IDI which is located at Makerere University. “If there is poor sanitation and say someone is keeping chicken and giving them antibiotics and for some reason they become resistant, that chicken poop can end up in a water source people are going to consume, and so animal-to-human and human-to-animal interactions are more can and lead to getting anti-microbial resistance from the environment,” Dr Kambugu says. “So we should be concerned about AMR in slums.” Dr Kambugu explains why people in low income settlements like Katanga are more vulnerable to AMR. “When someone from Katanga comes to see me with an infection that needs treatment for three to five days to clear and I don’t have that drug in the health unit, that person has to buy that drug and they may only afford treatment for one day.” He adds, “So they take the treatment for one day, then they feel better then after a week, it comes back. Poverty is one of the drivers of AMR because people take half doses and shortcuts, which becomes a problem.” To stem this problem, IDI has teams that do outreach programmes in settlements like Katanga, Kisenyi, Kalerwe to raise awareness on the dangers of self-medication and how it causes antimicrobial resistance. The drama groups carry out poems and kits to sensitize the masses in the very heart of the communities where the problem is prevalent. Dr Kambugu says one of the biggest challenges about anti-microbial resistance is the inability to measure it well. “It is like fighting a battle where you don’t know your enemy well.” “We are tracking AMR across several regional referral hospitals. We do see alarming trends. In gonorrhea, a common sexually transmitted infection, we see previously recommended treatment not working in 90% of the cases,” he says. Across the 13 regional referral hospitals, IDI microbiologists are observing that 30-50% of the isolates (pure species of microorganism that has been separated from a mixed culture and grown in a laboratory setting) do not respond to common antibiotics where previously there was a response. “That was the foundational work. We want to do a trend analysis where we look at things over time. But I would not be surprised if we find that this is getting higher.” Primary drivers of AMR “One of the drivers of antimicrobial resistance is that there is too much access. Anyone can go to a pharmacy, get the drug or even half the dose; Unfettered access leads to misuse,” Dr Kambugu says, “That comes in many forms; self-medication, use of antibiotics in poultry, agriculture, and the lack of regulation means any one can get them.” The other driver is overprescription. “In children a lot of respiratory tract infections, (flus and coughs) are caused by viruses but then you find medical practitioners and other healthcare workers prescribing antibiotics,” he explains. Limited awareness on use of antibiotics has been the other issue. He says there is a common tendency where a doctor does not prescribe an antibiotic but a mother says the child needs one and proceeds to buy the drugs. IDI established these findings in a research project called Drivers of Resistance in Uganda and Malawi (DRUM). The research addressed how human behaviour and antibacterial usage in the home, around animals and in the wider environment in urban and rural areas of Uganda and Malawi contributes to the spread of antibiotic resistance in bacteria. IDI has got support from one of its partners, the UK Fleming Fund, for work on AMR. These superbugs have made certain patient populations vulnerable. The treatment and management of infectious diseases has definitely changed because of resistance. “There are groups we are very concerned about because drug resistance leads to death,” Dr Kambugu says, “Patients in the intensive care unit (ICU). These have iv lines(small plastic tube inserted into the veins) catheters; all of these are points of entry of bacteria and a bug can jump from one person to another if there are no good infection control practices,” he says. He stresses that many times when people die because they had cancer it’s due to resistant organisms being the last stroke that kills the patient because their immunity has been suppressed. ICU and cancer patients are particularly vulnerable. “There are special forms of drug resistance, e.g. multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB). This happens for patients who don’t adhere to their treatment; TB is peculiar in that you have to treat people for sick months,” he warns. “If you are not well oriented or if you don’t get the right instructions then you may end up getting MDR-TB because you are swallowing the medicine haphazardly.” According to WHO, Uganda is one of the world’s thirty high-burden countries for TB and TB/HIV co-infection. Each year, approximately 91,000 people in Uganda get sick of TB with 32% of them being HIV-infected. Two out of every 100 people with TB have drug-resistant TB that is not cured by first-line drugs. In addition, approximately 15% of TB cases in Uganda are children aged below 14 years. On April 24, the New Vision reported a TB outbreak in Maracha district with 206 cases. The cases were among primary school children. It is six months since it was reported and there are now fears that these children could develop MDR-TB because the health facilities in Maracha may not be providing the best care. To address the country’s TB burden, the Ministry of Health (MoH) developed a robust TB and Leprosy Strategic Plan (2020/21-2024/25). The strategy highlights the implementation status of the country’s TB response in relation to the strategic direction, global evidence, and high-level advocacy. But the timeline has come to an end meaning more action plans are due. In addition, Centers for Disease Control (CDC) opened a MDR-TB treatment center at the Uganda Prisons Service which was the sole referral and management center for incarcerated patients with MDR-TB in Uganda. But this centre closed when USAID was shut down by the US government early this year. The closure of this centre was a strategic setback in the fight against TB and by extension, anti-microbial resistance. Children are another special category prone to antimicrobial resistance. “Because they are usually taken care of by adults…and if there are gaps in that adults’ understanding, then the children will be prone because of the suboptimal care they are getting which results in AMR,” Dr Kambugu says. The situation is compounded by the lower immunity of children including newborns. He adds that young people are prone to sexually transmitted diseases and by extension drug resistant STDs like gonorrhea. WHO cites antimicrobial resistance as one of the top global public health and development threats. Reports say AMR could cause 10 million deaths per year by 2050. Dr Hakim Sendagire, a biochemist and lecturer at Makerere Medical School told The Independent that in his work testing patient samples to look for bacteria, resistance usually hits 100%. “WHO has given us guidelines on antibiotics we should routinely check. Quite a number of medicines have become almost useless; we are moving away from drugs like ampicillin,” he notes with caution. As a result, he says that people have been introduced to sophisticated drugs. “We are worried about remaining with no antibiotics at all.” Doctors are now trying to combine antibiotics but the tests show the difficult road ahead. “We have moved from combining two to combining up to three drugs to treat the same infection.” The crisis has Uganda’s doctors and scientists worried. “We are quickly losing drugs that have been useful over the years. We are doing all sorts of maneuvers in the cultures (growing the bacteria in the lab) and testing it against the drugs to see which are still susceptible and resistant,” Dr Sendagire says. Managing patients with suspected or confirmed drug-resistant infections especially when laboratory support or second-line antibiotics are hard to access has been another challenge. It is a struggle between diagnosis, treatment availability, and cost showing the practical constraints doctors face in the battle against AMR. “It is really difficult every time you find a report of a patient of multiple drug resistance. It gets confusing because usually we move from one step to another but there are times you get patients and all available antibiotics are resistant,” he says. It often turns into a case of doctors trying out drug combinations to save the patient. “But they are just gymnastics and it’s difficult to predict. We try our best to give available drugs.” Dr Sendagire adds that there is currently no data on how many people succumb to infections due to antimicrobial resistance. “When people die we don’t usually test for the resistance of the organism but it’s one of the steps we are seeking.” High cost of treatment He also offered insights on how antimicrobial resistance is affecting clinical decision-making, patient outcomes, and the overall cost of treatment for ordinary Ugandans. “It is really challenging. A recent patient came with a urinary tract infection (UTI); we kept changing antibiotics because they were not working. Meanwhile the microorganisms are grown in the lab for five days before you get the result.” He says the fact that patients have to start on treatment even before they get lab results is a major setback in managing the crisis. Within these five days, doctors have to contain the fever using the available antibiotics. “First day it is not working, second day, it is not working, and a third day before you finally get results and by the time you are done, you have cost the patient lots of money,” he says, stressing that this particular patient was charged a total of Shs5 million. “It’s both expensive to the patient and to the government. People remain sick for a long time and they cannot work and contribute economically.” A study released in July 2025 by Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) done in 14 African countries showed the growing spread of drug resistance and underscored the urgent need to strengthen laboratory testing, data systems, and health planning to tackle hard-to-treat infections. It was titled Mapping Antimicrobial Resistance and Antimicrobial Use Partnership (MAAP). The other researchers were the African Society for Laboratory Medicine (ASLM), One Health Trust, and other regional partners. “Researchers reviewed more than 187,000 test results from 205 laboratories, collected between 2016 and 2019 across Burkina Faso, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.” The Africa CDC report noted that people over the age of 65 were more likely to have resistant infections than younger adults. “Patients already admitted to hospitals had a 24 per cent higher risk, likely due to increased exposure to antibiotics. Previous use of antibiotics was also linked to higher resistance.” Dr Yewande Alimi, the One Health Unit Lead at Africa CDC, issued a clarion call “For African countries, AMR remains a complex problem, leaving countries with a million-dollar question: ‘Where do we start from?’ This study brings to light groundbreaking AMR data for African countries. We must act now—and together—to address AMR.” This story was supported by the Africa Centre for Media Excellence