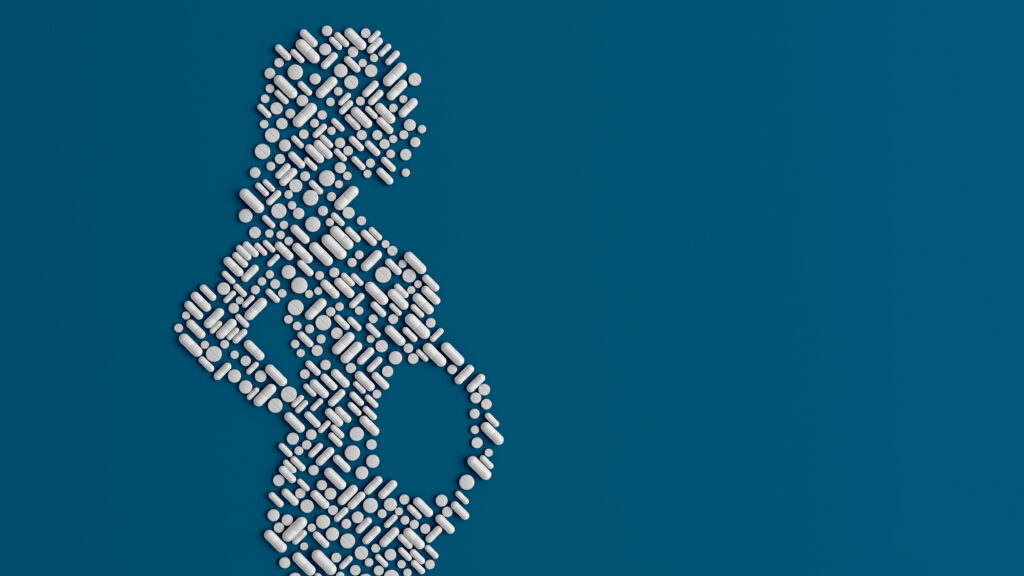

When I ask a patient at her first prenatal exam what medicines she’s taking, she usually says, “none.” Those who were previously taking prescription or over-the-counter drugs, even for serious conditions, have usually stopped, often at the suggestion of another doctor or a family member. “They said I should talk to you first,” she tells me. “To make sure it’s safe.”

As far as we know, many common medications are quite safe in pregnancy. But try telling this to a pregnant woman who’s taking medications for depression, migraine headaches, or seizures. What does “as far as we know” even mean? How can she be certain that she is making the right decision for herself and her baby?

Advertisement

These are hard questions to answer — and they’re about to get harder, as Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has apparently become interested in the idea that Tylenol use in pregnancy might be a cause of autism. A report from HHS to this effect is expected in the coming weeks.

News outlets reporting on this “controversy” have correctly identified that there is absolutely no scientific evidence for a causal link between Tylenol (or any other drug) and autism. Instead, multiple imperfect studies have found conflicting evidence: Some show non-causal associations between Tylenol use in pregnancy and neurodevelopmental disorders; others show no association at all. Another way of saying this is: There’s no proof that taking Tylenol while pregnant causes autism. But we can’t say conclusively that it doesn’t. This is true of many common drugs.

What, then, are pregnant women (and their doctors) to do? Is it safe to treat their headache, depression, nausea, etc. — or not?

Advertisement

I would argue that we should be asking a different question, particularly at this moment of crisis for reproductive rights in the U.S.: What does it mean to regard safety as the sole measure of a drug’s acceptability in pregnancy? Whose safety are we really concerned about — and whose well-being and autonomy are we willing to sacrifice in order to protect it?

The unfortunate truth is that we are unlikely ever to get definitive evidence for the safety of any drug in pregnant women, whether it’s a medication like Tylenol that’s been around for decades, or newer drugs like mRNA vaccines. This is not merely because of lack of funding for women’s reproductive health research (although that’s a part of it). It’s also because pregnant women are effectively barred from participating in drug trials, ostensibly — and ironically — for their own “safety.”

Researchers and regulators have historically treated pregnant women — along with children, incarcerated adults, and patients with impaired decision-making capacity — as “vulnerable” subjects in clinical trials. This designation is intended to protect research subjects against coercion, or from consenting to experimental clinical interventions whose risks they don’t fully understand. This despite the fact that, as argued in an essay in Health Affairs last year, “nothing about pregnancy impairs one’s ability to understand a consent form, comprehend the implications of clinical research studies for both the pregnant person and their fetus, or make the free decision to enroll or not enroll in research.”

Thankfully, in 2017, pregnant patients were removed from the list of vulnerable populations in federal regulations. But many private and government institutions that approve research protocols, including the Food and Drug Administration, still classify pregnant women as “vulnerable,” making enrollment in randomized control trials extremely difficult, if not impossible. Most of our data on medication use in pregnancy instead comes from retrospective studies, which are notoriously fraught with recall bias and other problems. As multiple medical societies have pointed out, the net effect is counterintuitively one of harm: Because researchers won’t include them in drug trials, pregnant women are denied the potential benefits of a whole host of medications in the name of “safety.”

Advertisement

This evidence vacuum leaves doctors with little more to offer our patients than vague and often conflicting advice: “It’s probably safe.” “We don’t know for sure.” And the old foreboding aphorism: “Use the lowest possible dose for the shortest period of time.” Pregnant women are left understandably terrified to take 500 mg (a single tablet) of Tylenol. The unspoken message is: Better just to tough it out. For the safety of your baby, your suffering is worth it.

We must see the dearth of appropriate research — and guidance — around medication use in pregnancy for what it is: unabashed paternalism that disguises concern for the fetus as concern for the mother. Though less sinister, it’s akin to the disingenuous sentiment that claims pregnant women need to be protected from doctors who would persuade or trick them into having abortions — as though women, perfectly capable of making their own health care decisions when not pregnant, instantly become “vulnerable” to coercion and confusion when carrying a fetus.

So how can we actually help — rather than merely control — pregnant women? I’ve spent more than a decade of counseling pregnant women, and I can tell you two things that they respond to.

The first is hard facts. They want to know the likelihood of a harmful or beneficial outcome to them or their baby — in numbers. Although it’s become almost an almost meaningless adage, more research is needed, including more research dollars from the federal government dedicated to women’s reproductive health.

Such funding is unlikely to materialize under the current administration, so in the meantime doctors must change how we think about and talk with our patients. Because the second thing pregnant women respond to is trust. Doctors must be bold enough to fill the information vacuum with encouragement and empowerment for women. The truth is, I usually skip the standard line about using “the lowest possible dose for the shortest possible time” — a commonsense guideline that most people, pregnant or not, follow intuitively. Instead I remind my patients that these are very personal decisions, and that different individuals respond differently to risk, stress, and pain: “Only you know what it’s like to live and to be pregnant in your body. No one else can tell you what to do, including me.”

Advertisement

Under the current administration, and in a society moving rapidly toward silencing, controlling, and even criminalizing pregnant women, it’s critical to keep our attention on the big picture. As a doctor and a mother, as much as I hope for more answers about what causes autism, the most important question for me is this: How can I treat pregnant women as fully autonomous, capable adults who can make their own informed and reasonable decisions? No matter what the new HHS report says about Tylenol, my answer to this question won’t change.

Christine Henneberg, a family physician, is the author of “Boundless: An Abortion Doctor Becomes a Mother,” and the novel “I Trust Her Completely.”