Trump’s plan to label antifa a “terrorist organization” likely to face legal hurdles: “You can’t prosecute an ideology”

Washington — President Trump announced on social media Wednesday that he’s designating antifa as a “major terrorist organization.” But what that action would mean for the movement remains unclear, given that antifa has no official leadership or organization structure, and the president lacks authority to designate domestic terrorist organizations, experts say.

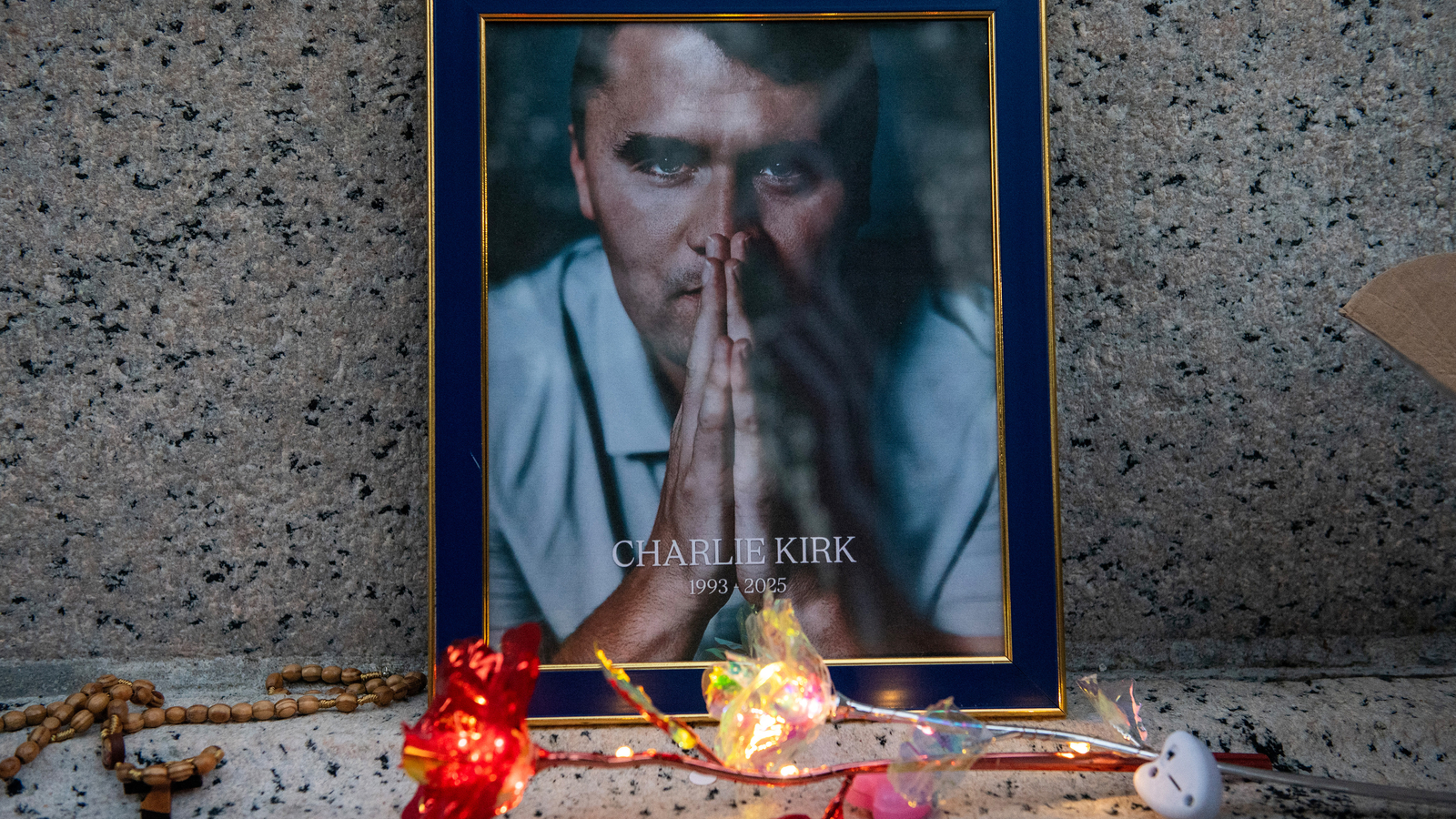

The president’s announcement comes as he and his supporters continue to denounce “radical left wing political violence” following the assassination of conservative activist Charlie Kirk last week. After Kirk’s killing, Mr. Trump blamed rhetoric from the “radical left,” saying that it is “directly responsible for the terrorism that we’re seeing in our country today, and it must stop right now.”

Officials described the attack on Kirk as “targeted,” and family members of the suspected shooter, Tyler Robinson, said he had “become more political” in recent years. Robinson wrote in text messages to his roommate that he had carried out the attack because he “had enough of [Kirk’s] hatred,” according to court filings. There has not been evidence presented to the public linking Robinson to antifa.

This is not the first time Mr. Trump has argued antifa poses a threat — in his first term, he claimed the movement was behind looting and rioting during protests against police brutality in 2020. A November 2021 report on anarchist and left-wing violence in the U.S. from George Washington University’s Program on Extremism and the National Counterrorism, Innovation, Technology and Education Center noted that the first Trump administration largely labeled the threat from anarchist violent extremists as originating from antifa.

What is antifa?

Short for “anti-fasict,” antifa activism can be traced back to antiracists who opposed the activities of members of the Ku Klux Klan and neo-Nazis, according to a June 2020 report from the Congressional Research Service. But the movement gained attention after the violent clashes between white nationalists and anti-racism protesters in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017.

The Congressional Research Service describes antifa as “decentralized” and lacking a “unifying organizational structure or detailed ideology.” Instead, it consists of “independent, radical, like-minded groups and individuals” that largely believe in the principles of anarchism, socialism and communism.

“There is no single organization called antifa. That’s just not the way these activists have ever organized themselves,” said Michael Kenney, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh who has studied antifa. “There’s tremendous variation inside that movement, even on issues like political violence.”

The FBI has warned about violence perpetrated by antifa adherents, and in 2017, then-FBI Director Chris Wray told Congress that the bureau was looking into “a number of what we would call anarchist extremist investigations, where we have properly predicated subjects who are motivated to commit violent criminal activity on kind of an antifa ideology,” according to CRS.

Wray, who was appointed FBI director by Mr. Trump during his first term, also acknowledged in congressional testimony in 2019 that the FBI doesn’t investigate ideology, but does investigate violence. Then, in 2020, he said antifa is a “movement or an ideology,” not an organization.

A 2020 assessment from the Center for Strategic and International Studies found that far-right attacks and plots have outpaced those from other perpetrators, including far-left networks. A 2022 study from the University of Maryland’s National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism also found that “right-wing extremists” are more violent than left-wing actors.

But CSIS said its data has indicated a rise in violent activity by “antifa extremists, anarchists and related far-left extremists,” which it said is likely connected to the “concurrent increase in violent far-right activity.”

What could Trump’s suggested designation do?

Mr. Trump announced in May 2020 that the U.S. would be designating antifa as a “major terrorist organization following nationwide unrest in response to the death of George Floyd,” but nothing followed from that.

Luke Baumgartner, a research fellow at the Program on Extremism at George Washington University, said the president does not have the authority to designate domestic terrorist organizations, even if this were an “organization.”

“There is no legal mechanism that I’m aware of within U.S. code that would give the president or the federal government the power to declare a domestic ‘group’ as a major terrorist organization or a major terrorist group,” he said.

The administration could, however, shift antifa to a higher priority for federal law enforcement, Baumgartner said, which could lead to more frequent investigations or arrests.

The FBI and Department of Homeland Security don’t officially designate U.S. extremist groups as “domestic terrorist organizations,” in part because of First Amendment concerns, according to CRS.

A 2023 report from the research entity also noted that the government does not provide a “precise, comprehensive, and public explanation of any particular groups it might consider to be domestic terrorist organizations,” and it warned that listing groups in that way may infringe on free speech rights or “the act of belonging to an ideological group, which in and of itself is not a crime in the United States.”

“At this point, it’s not a crime in America to have ‘leftist’ political beliefs along the lines that some anti-fascists do,” Kenney said.

He added that designating groups as domestic terrorist organizations could also raise Fourth Amendment concerns regarding surveillance.

“Do we as Americans still enjoy the right to free speech, to nonviolent political expression of our views, however unpalatable the Trump administration might find those views? Yes,” Kenney said.

While the U.S. does not have a list of domestic terrorist organizations, it does have a Foreign Terrorist Organizations list. Among the groups on the list are Hamas, al Qaeda and ISIS, which are known to operate transnationally. These groups are not related to the antifa movement.

Kenney said that if the president were to try to designate antifa as a foreign terrorist organization, it would unlock tools like economic sanctions to bring greater pressure on the movement. Mr. Trump hasn’t said he has this in mind, though he said he’d recommend “those funding ANTIFA be thoroughly investigated.” A foreign terrorist designation would make it a crime to provide material support to antifa. Making this designation would present other challenges, however.

“When the president refers to antifa, whether in remarks to reporters or speeches, he’s usually referring to domestic non-state actors and domestic incidents, so how are they going to portray that as foreign? That’s not clear to me,” Kenney said.

Can the Justice Department charge someone associated with antifa with domestic terrorism?

No. The FBI defines domestic terrorism as “violent, criminal acts committed by individuals and/or groups to further ideological goals stemming from domestic influences, such as those of a political, religious, social, racial, or environmental nature.” But it is not a chargeable offense under federal law.

“You can’t prosecute an ideology,” Baumgartner said.

But there are numerous federal criminal statutes that could apply to domestic terrorism.

In the case of Dylann Roof, a white supremacist who killed nine Black parishioners at a church in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015, he was convicted of 33 counts of federal hate crimes, obstruction of religious exercise and firearms charges.

Payton Gendron, who killed 10 Black people at a supermarket in Buffalo, New York, in 2022, is facing federal hate crime and weapons charges. Gendron also pleaded guilty to a state terrorism charge.

Thirty-two states and the District of Columbia criminalize the act of domestic terrorism, according to the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law. In 21 states and D.C., it is a crime to provide support to further an act of terrorism or a terror.

Harsher punishments a possibility

But Baumgartner said that where alleged domestic terrorism does come into play at the federal level is in increased penalties for perpetrators. Prosecutors have sought harsher punishments for felony offenses that “involved, or was intended to promote, a federal crime of terrorism.”

The Justice Department asked federal judges in 2023 to apply a terrorism adjustment in cases involving members of the Proud Boys and Oath Keepers, far-right organizations whose members were convicted on charges stemming from the Jan. 6 Capitol attack, including seditious conspiracy.