Trump wants to revoke birthright citizenship. We have it to thank for Americans like Bruce Lee.

This piece is adapted from the book Water Mirror Echo by Jeff Chang. Copyright © 2025 by the author and reprinted with permission of Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

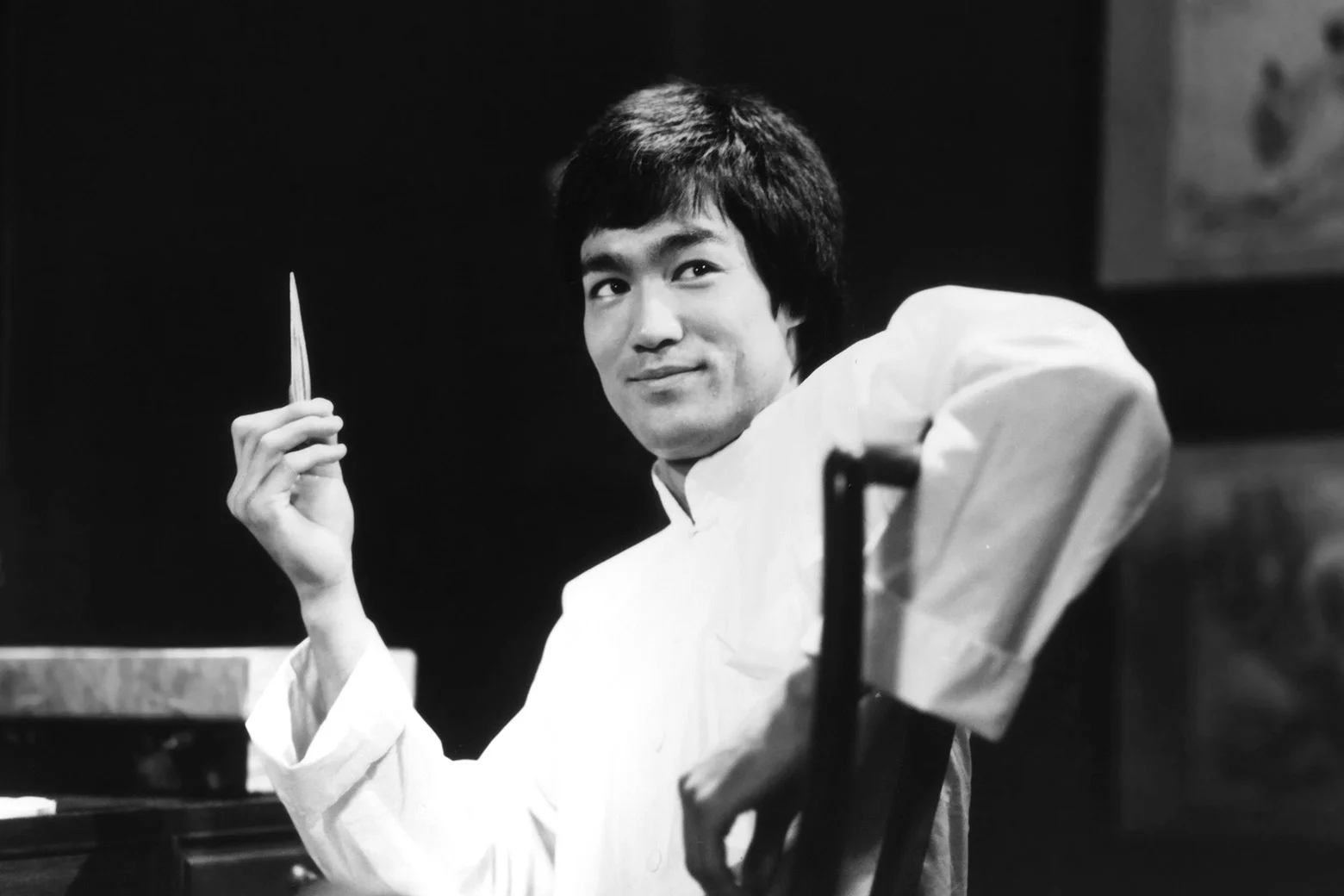

“That I should be an American-born Chinese was accidental,” Bruce Lee once mused, “or it might have been by my father’s arrangement.”

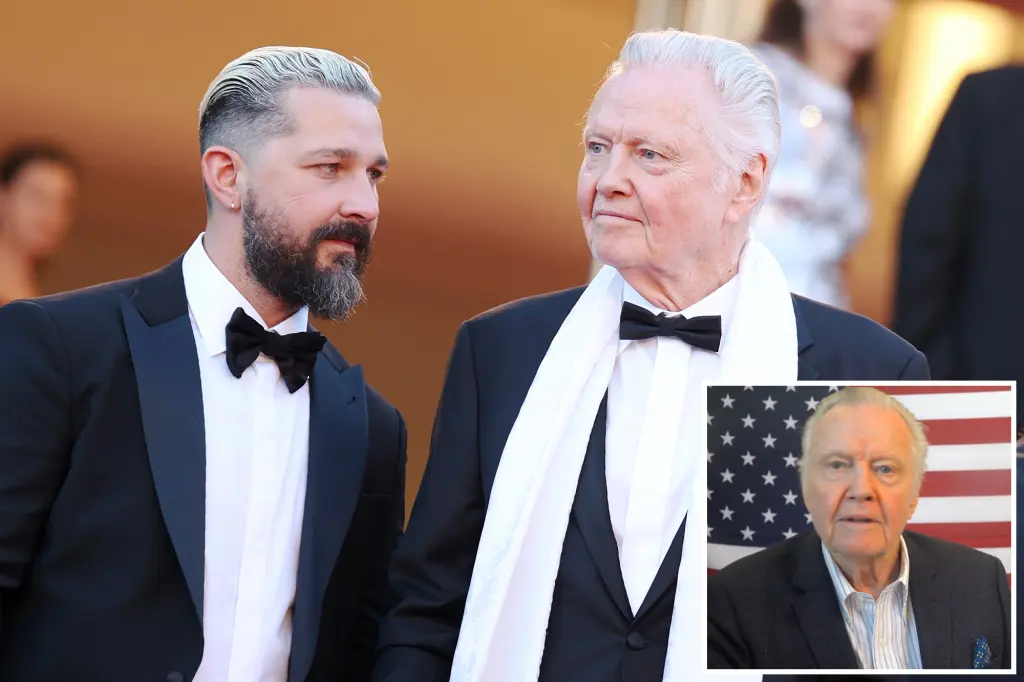

Lee, cinema’s greatest martial artist and the most famous Asian American of all time, was born in San Francisco’s Chinatown on Nov. 27, 1940, in the segregated Chinese Hospital. His parents, Li (also anglicized as “Lee” in the U.S.) Hoi Chuen and Grace Ho, had come from Hong Kong a year earlier, sailing across the Pacific to perform Cantonese opera for Chinese American audiences across the United States.

They left behind three small children in the care of Hoi Chuen’s mother and landed in a country where Chinese were still unfree, alien, and unwelcome. They were here on temporary work visas. But even if they had migrated here wanting to become citizens, they could not. The Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned all immigration of Chinese with few exceptions, was very much still in effect.

Had he been born today, Bruce Lee might have been called—in the divisive language we now use to describe immigration—an “anchor baby.” The derogatory term conjures the dubious notion that many migrant families are conspiring across generations to secure U.S. citizenship, and using their own infants to achieve that goal.

But the story of Lee’s family reveals the absurdity of that idea. Migration is always so much simpler and so much more complex.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

In 1939, with bombs falling near Hong Kong, the opera collapsed and jobs vanished. Hoi Chuen, born in the Pearl River Delta, had risen from poverty to become one of Cantonese opera’s great chou sang, or comic masters. Grace Ho, born into Shanghai privilege but disinherited after eloping with him, had experienced the steep drop from colonial wealth to uncertainty.

Together they gambled on a tour of America through the Mandarin Theatre in San Francisco. They calculated that, even with war raging across the border in southern China, leaving behind their children to secure work and necessary funds would aid their chances of survival should war come to Hong Kong.

Had they come hoping to settle permanently in the U.S.? It’s highly unlikely.

Their first experiences entering the country reminded them of the second-class treatment that Asians in America faced. At the San Francisco docks the Lis were segregated from citizen passengers, then ferried to the Angel Island immigration station in San Francisco Bay, where, for three decades, most Chinese migrants had been detained.

There, the Lis dropped their luggage and proceeded to an administrative building, where they were separated from white migrants, then from each other. In a stuffy room, Hoi Chuen and a dozen other Asian men were stripped and inspected by medics for hookworm. They were led to a crowded men’s quarters, full of bunks already mostly occupied by hundreds of other Chinese migrants. Many had been waiting for a month or more to hear about their cases.

Carved into the barracks’ walls were hundreds of poems, a graffiti feed in Chinese characters of throttled hope. One captive named Chan had cut these words into the wood:

America has power but not justice.

In prison, we were victimized as if we were guilty.

Given no opportunity to explain, it was really brutal.

I bow my head in reflection, there is nothing I can do.

Knowing what was awaiting them on these shores, the Lis had already carefully prepared papers for their arrival. Hoi Chuen’s non-immigrant visa listed his purpose for visiting as “theatrical work only.” Grace’s papers described her as an “actress (wardrobe woman).”

The Mandarin Theatre staff had received approval from the Department of Labor to admit them. But the Immigration and Naturalization Service required that they secure a bond of $1,000 each (more than $22,000 in today’s dollars) that ensured they were “over 16 years of age,” remained “in possession of proper visas” and “free [of] contagious disease,” and would not become “public charges”—bureaucratese for “recipients of government funds or services.”

After being cleared, the Lis were ferried back to San Francisco, shadowed by an immigration official. They were met at the pier by a theater representative, who produced more papers for yet another official. Once cleared, they headed directly to Chinatown to take their residence in the Mandarin’s quarters in a blind alley at 18 Trenton St., a block from the Chinese Hospital.

That day, Hoi Chuen later told his children, he had come to understand how unfree the Chinese were in America.

Chinese exclusion had produced new language—words needed to be invented for novel functions like “deportation”—and a new regime of papers. All Chinese Americans were required to carry “certificates of residence” and “certificates of identity” that verified their status as legal immigrants. They would be issued only after the applicant was vouched for by at least one white witness. Anyone without these papers became, in the historian Erika Lee’s words, “America’s first undocumented immigrants.” When migrants began crossing the Canadian and Mexican borders, Congress formed the precursor of today’s Border Patrol and ICE raid goons, gangs of white deputies who called themselves “Chinese catchers.”

While his wife stayed in San Francisco, Hoi Chuen set out to tour the U.S. But he would only see the country through its Chinatowns, neighborhoods where racial segregation was enforced by laws, housing covenants, and custom. The cross-country trip to New York was particularly tense and taxing. “They weren’t allowed to get off the train whatsoever,” said Robert Lee, Hoi Chuen and Grace’s youngest son. “The only time they could get off was when they arrived at the station in New York.” In each tour city, immigration officials tailed them until they got back on the train.

It is hard to believe that Hoi Chuen and Grace would have wanted to subject any of their children to such treatment.

Because Bruce had been born in San Francisco, and though there is nothing in his papers to suggest whether it had been by “accident” or “arrangement,” he was a U.S. citizen. His birth would link him forever to the noble history behind the idea of birthright citizenship.

Speaking in 1867, just after the Civil War, as the United States was struggling to shape its future, the Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass said of the Chinese, “They will cross the mountains, cross the plains, descend our rivers, penetrate to the heart of the country, and fix their homes with us forever.” Douglass and the Black freedom movement had pushed the country to grant citizenship to all born on its soil, an idea called “birthright citizenship.” He said, “I want a home here not only for the negro, the mulatto, and the Latin races, but I want the Asiatic to find a home here in the United States, and feel at home here, both for his sake and for ours. Right wrongs no man.”

Douglass’ expansive vision for America did not prevail then. Between 1890 and 1919, as 16 million people immigrated from Europe, only 315,000 were accepted from South Asia and East Asia.

But birthright citizenship had been sealed in the 14th Amendment in 1868. To the exclusionists who wished to preserve a white settler nation, Asians born in the States—the “American-born Chinese,” the first “second generation” of Asian Americans—represented a vexing new problem.

When Wong Kim Ark, a cook born a generation later in San Francisco, returned from a trip to China, he was barred reentry on the grounds that the Exclusion Act stripped him of citizenship. But Wong fought all the way to the Supreme Court and won in 1898. The court affirmed that the 14th Amendment granted citizenship to all born on U.S. soil, regardless of parents’ nationality.

Wong moved to Texas for a new start. But he was jailed there for four months by immigration officials who refused to believe he was a citizen. He continued to visit China, but on every return was required to fill out a form entitled “Application of Alleged U.S. Citizen for Reentry into the United States,” and subjected to what historian Erika Lee called “a barrage of humiliating interrogations.” When his sons applied for entry to the country, they were detained at Angel Island. Two of them were rejected because officials refused to believe his children were his own. One won his appeal. The other submitted himself to deportation. Still holding his certificate of identity, Wong Kim Ark booked a final ship passage to Toisan. Like his son, he gave up on America. In today’s dehumanizing language, he “self-deported.”

In 1941, with Hoi Chuen’s work complete, the Lis prepared to return to Hong Kong and filed papers to verify Bruce’s U.S. citizenship status. Hoi Chuen and Grace had worked with the Mandarin Theatre staff to hire an immigration law firm—somehow named White & White—to help them fill out Form 430, the application for a Citizen’s Return Certificate, on behalf of their son, whom they listed as “Lee Jun Fon (Bruce Lee).”

Baby Bruce appears in a picture attached to the application, dated March 31, 1941, showing infant and mother. He is dressed in a knit sweater. His eyebrows are raised, cheeks puffed, lips pursed as if drawing an expectant breath, alert and ready for anything.

During their interrogations, the “alleged father” and “alleged mother,” as they were called, were asked to corroborate their ages, places of birth, address in San Francisco, marriage date, the names of their sons, alive and dead, and their daughters. Hoi Chuen was asked, “Has Lee Jun Fon any other name?” He joked, “The doctor gave him an American name, but I can’t pronounce it.” Grace was asked, “Do you intend to have Lee Jun Fon remain with you until he grows to manhood?” She said, “When he is able to go to school, I intend to have him come back here and attend school.” Both were advised, “If Lee Jun Fon remains abroad for more than six months, he may be obliged to submit definite proof that he has not expatriated himself, if he should wish to reenter the United States.” Did they understand? Each of them answered through their translator—yes. In the section of Form 430 asking the reason for Bruce’s departure, the lawyers typed: a temporary visit abroad.

Bruce returned to the U.S. 18 years later. Forced to live in segregated communities, he found common cause with Black Americans, Japanese Americans, Filipino Americans, Latinos, poor whites, and other outcasts who taught him what it really meant to be a racialized minority, a true underdog.

Upon assuming office this year, one of President Trump’s first executive orders sought to revoke birthright citizenship from any child of parents here under temporary visas or who are not lawful permanent residents. Trump’s intention is to overturn over a century of settled law. If the order—which has been halted until the Supreme Court rules on its doubtful constitutional merits—had been in place when Bruce was born, he would have certainly been subject to deportation. In this, his fate would have been no different than that of Vivek Ramaswamy, Kamala Harris, or Nikki Haley, all American citizens born to migrant parents in the U.S.

While polls have consistently shown that a majority of Americans believe refugees and migrants deserve the chance to belong and thrive in this country, the politics of migration eight months into the Trump administration has swung far beyond the reactionary. The America of today—in which anti-alien land laws have returned, in which the history of nonwhite communities are being erased from school curricula, in which migrants are indiscriminately seized, held, and deported, regardless of probable cause—is unrecognizable to many, even Trump voters, who have called this country home. In that light, it may be a small—yet real and necessary—comfort to remember that many of our greatest Americans, like Bruce Lee, became that way despite the ideologies and laws that were stacked against them.