Copyright Cable News Network

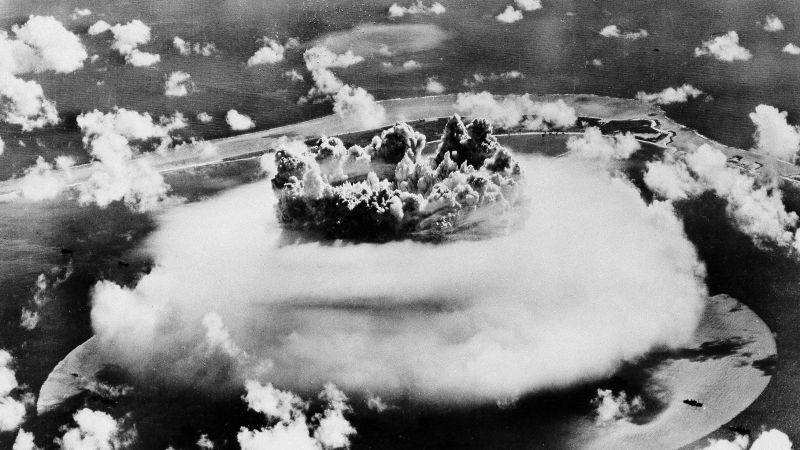

President Donald Trump’s call for the United States to resume testing of nuclear weapons last week has experts scratching their heads. What did he really mean – exploding a warhead or testing delivery systems? Does he understand how nuclear weapons work? How will US nuclear adversaries react? And some experts caution that the testing of nuclear warheads – creating actual nuclear explosions – hurts humans and can have lasting consequences for generations. Few people know the harm nuclear testing can do better than inhabitants of the Marshall Islands, a country of 1,200 islands and atolls in the Pacific, which was a US-administered trust territory of the United Nations from 1947 to 1986. As it developed its nuclear arsenal post-World War II, the US exploded 67 nuclear bombs there between 1946 and 1958. Those detonations had the explosive equivalent of one Hiroshima-sized atomic bomb every day for 20 years, according to a 2025 report from the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research (IEER). The radiation effects have been ruinous, according to US government reports cited by the Atomic Heritage Foundation, which said the testing was responsible for 55% of cancers on some of the islands’ northern atolls. And the effect has been more widespread than in the islands. Scattered by winds in the atmosphere, the nuclear fallout from those tests has resulted in about 100,000 excess cancer deaths worldwide, according to the IEER study. Fallout hotspots were detected as far away as Sri Lanka and Mexico. Related diseases come from isotopes in the nuclear fallout that can penetrate the human body and cause mutations in DNA, according to a 2024 paper from the American Society of Clinical Oncology Journal. The isotopes can remain in the environment years after testing, afflicting those exposed with cancers including lung, leukemia, lymphoma, thyroid and breast, the paper says. And the US past nuclear tests weren’t confined to the Pacific islands. The Nevada Test Site in the Mojave Desert saw 100 atmospheric tests from 1951 to 1962, and 828 underground tests, the last of those being in 1992. Though underground testing is considered safer, 32 of those tests in Nevada resulted in fallout escaping into the atmosphere, according to a 1993 UN report. “We know that nuclear testing has devastating consequences on communities and ecosystems throughout the United States, many of whom are still seeking reparations for harms caused by US nuclear testing during the Cold War,” said Matt Korda, associate director at the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists. “Resuming testing would almost certainly inflict new harms on those groups,” Korda told CNN. Tragic nuclear legacy In the Marshall Islands, the wounds of nuclear testing are still raw. “This isn’t fiction, nor the distant past. It’s a chapter of history still alive through the environment, the health of communities, and the data we’re collecting today,” Greenpeace activist Shaun Burnie wrote after visiting the islands earlier this year. The environmental group staged a voyage to the Marshall Islands from March to April this year to document their state and to take scientific samples that will go into a coming report on the islands. On tiny Runit Island, part of Enewetak Atoll, sits “the dome,” a structure 377 feet (115 meters) in diameter, made of concrete about half-a-meter thick. Underneath it lies 85,000 cubic meters of radioactive waste gathered in a 1970s effort to clean up the islands, according to Greenpeace. Because the crater beneath the dome is not lined, as newer nuclear waste disposal sites are, “these substances are not only confined to the crater – they are also found across the island’s soil, rendering Runit Island uninhabitable for all time,” Burnie wrote after the organization’s visit. The island “may be one of the most radioactive places in the world,” he said. And with climate change, rising sea levels now threaten the structural integrity of the aging dome. No one’s really sure how far the effects of that waste might spread. “That dome is the connection between the nuclear age and the climate change age,” activist Alson Kelen said in a 2018 report from the Australian NGO Safeground. Burnie said the radiation in the environment has changed the lives of the 300 current residents of the entire Enewetak Atoll. It’s been taken up by the roots of their coconut palms, contaminating the fruit, making it unmarketable. “The radioactive legacy has robbed them of income and opportunity,” Burnie said of the islanders. It’s not just agriculture that’s been affected, according to the IEER report. As their way of life has deteriorated, traditional skills have been lost, such as the skill to navigate the open ocean, a necessity for commerce and even reproduction. “Reading the waves was ‘indispensable as the sole means of collecting food, trading goods, waging war and locating unrelated sexual partners,’” the IEER report says, quoting a 2016 New York Time Magazine report on island mariners. Speaking to the United Nations Human Rights Council in 2024, UN Deputy High Commissioner Nada Al-Nashif said the legacy of testing has disconnected indigenous Marshallese from their culture. “The human rights impacts of the nuclear legacy are not limited to what is known and easily quantifiable. They are also rooted in pain that cannot be measured and facts that remain unknown,” she said. Castle Bravo and Bikini Atoll About 200 miles to the east of Enewetak is Bikini Atoll, the site of the largest nuclear weapons test ever conducted by the US. Known as Castle Bravo, it was a thousand times more powerful than the Hiroshima bomb. In 1946, Bikini Atoll had 167 residents. Before the Castle Bravo test, US Navy officers persuaded them to leave their homes, “for the good of mankind.” “He explained that they were a chosen people and that perfecting atomic weapons could prevent future wars,” and that one day they’d be allowed to return, an Atomic Heritage Foundation history says. Today, Bikini is uninhabited, spare a few caretakers. Radiation levels remain too high for full-time habitation, something that was determined after Bikinians were allowed to return in 1969 and began suffering radiation-related illnesses. The island was closed again in 1978. “Most of the new generations of Bikinians have never seen their home island,” Greenpeace’s Burnie wrote. Greenpeace’s final stop on its island tour this year was Rongelap Atoll, which was blanketed by ash from the Castle Bravo test on Bikini, about 125 miles (200 kilometers) to the northwest. In a 2024 report, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) talked about the effects of that ash – called “Bikini snow” – on the population. “It burned their skin and eyes, and they quickly developed symptoms of acute radiation sickness,” the report said. And the effects lingered. “For decades after the tests, women in the Marshall Islands gave birth to severely deformed babies at unusually high rates. Those born alive rarely survived more than a few days. Some had translucent skin and no discernible bones. They would refer to them as ‘jellyfish babies,’ for they could scarcely be recognised as human beings, the ICAN report said. Wanting relief from the effects, Rongelap residents evacuated the island in 1985 with the help of Greenpeace, resettling on two islands in Kwajalein Atoll, both just a handful of miles from the US military’s active Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site, which it says supports nuclear-capable missile testing as well as intercepts. The last major test While the Marshall Islands hasn’t seen a nuclear test since 1958 – the current US test site is underground in Nevada – the last test in the Pacific was in 1996, by France, one of 193 tests Paris conducted at South Pacific atolls over 30 years. Approximately 110,000 people suffered from radiation illnesses from the French tests, according to a 2021 report from the French investigative journalism site Disclose, Princeton University and Norwegian NGO Interprt. “Leukemia, lymphoma, cancer of the thyroid, lung, breast, stomach … In Polynesia, the experience of French nuclear tests is written in the flesh and blood of the inhabitants,” the report says. That last French test, on January 27, 1996, resulted in large international protests and a boycott of French goods. A day later, then French President Jacques Chirac announced his country would no longer test nuclear weapons. At the end of July 1996, China tested a nuclear device at its Lop Nur site in remote northwestern Xinjiang. It would be the last test by a major nuclear power. In September 1996, the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) opened for signature. It obligates signees “not to carry out any nuclear weapon test explosion or any other nuclear explosion.” The US, Russia and China quickly signed it but have not ratified it. Still, the three powers have abided by it, even though it remains unenforceable as it still needs the ratification of nine states. The only nuclear tests known to have been conducted worldwide since 1996 are by India (two in 1998), Pakistan (two in 1998) and North Korea (six from 2006 to 2017). None of those countries had signed the treaty. ‘A perilous moment’ Trump’s social media post on Thursday calling for the US to begin testing again is raising fears of a new nuclear arms race – and more devastating consequences for the people of the planet. “This is a perilous moment,” read a statement from the anti-nuclear group Ploughshares, calling the US president’s announcement “reckless, needless and dangerous.” As the US would test its weapons under the Nevada desert, the Marshall Islands is highly unlikely to see another nuclear explosion within its borders. But the islands will forever have a testament to the effects of nuclear weapons. The radioactive half-life of plutonium-239, one of the remnants of US nuclear testing there, is 24,110 years.