By Caitlin Babcock

Copyright csmonitor

When President Donald Trump said Sept. 15 that his administration had reached a deal with China to sell TikTok ŌĆō a popular social platform built around catchy short videos ŌĆō he said it would come as happy news to the appŌĆÖs millions of users. But they may not have been on edge. Despite being banned in January, TikTok has remained fully operational as the Trump administration did not enforce the law, saying it was negotiating a deal.

On the day before President TrumpŌĆÖs inauguration, U.S. app stores faced penalties of $5,000 per TikTok user if they continued to distribute or host the app. Congress, citing concerns that the Chinese government could gain access to TikTok usersŌĆÖ personal data, had come to a rare bipartisan consensus: It passed a law requiring TikTok to be banned unless China signed off on a sale by ByteDance, the appŌĆÖs parent company.

Extensions ordered by Mr. Trump have kept the app available and the ban from being enforced. But the future of TikTok remained unresolved.

Even if a deal with China occurs, the journey has raised a lasting question about the balance of powers and whether a president can simply decline to enact a law passed by Congress.

What do we know about the TikTok deal?

The Trump administration said Monday it has reached an agreement with China to keep TikTok running in the United States. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent called the agreement a ŌĆ£framework,ŌĆØ and said Mr. Trump will meet with Chinese leader Xi Jinping on Friday to complete the deal.

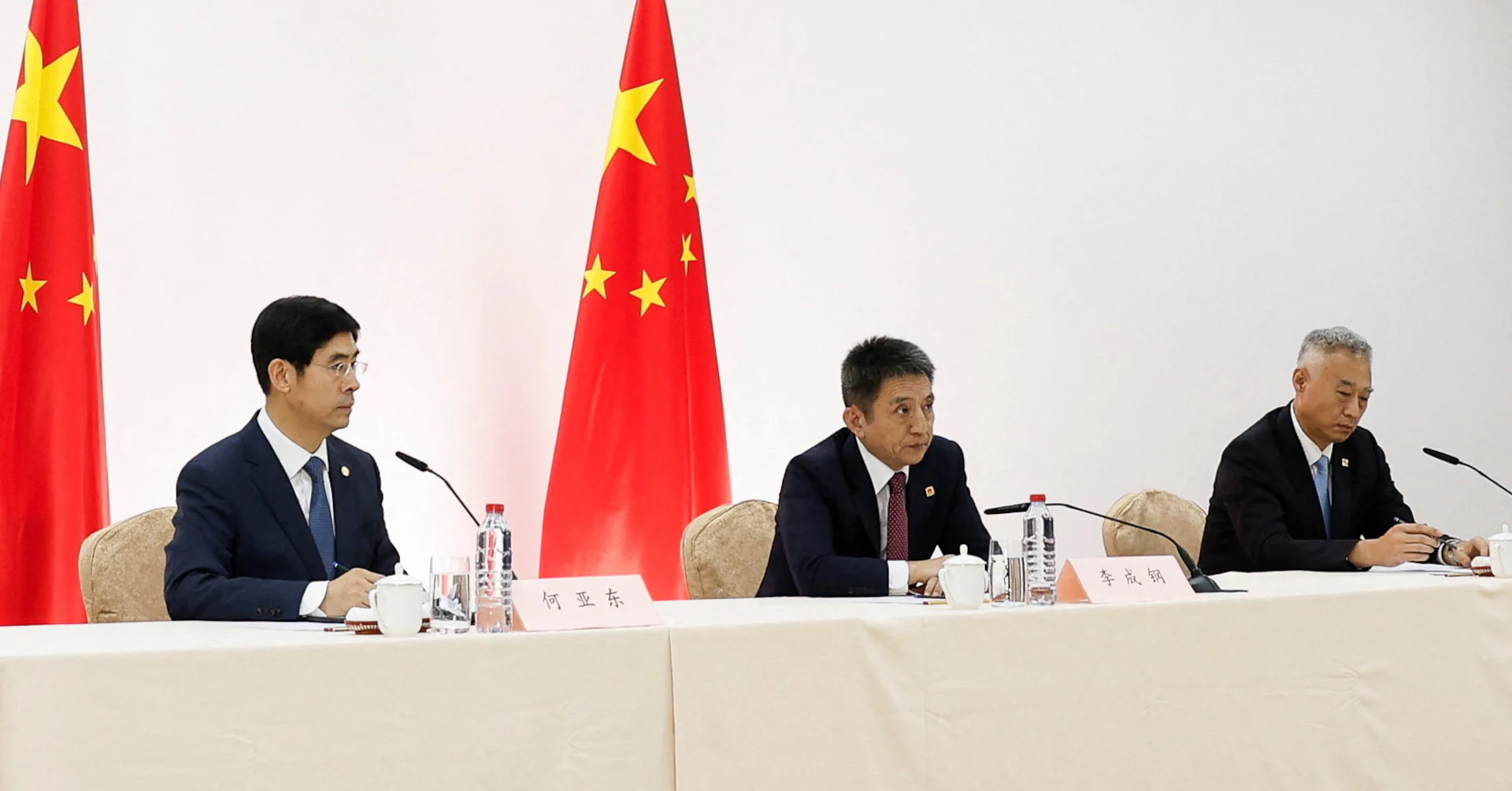

The U.S. and China had been engaged in talks in Madrid this weekend to discuss trade and other issues. The administration has not released details about the deal, including who TikTokŌĆÖs proposed buyer is.

Mr. Bessent said the deal addresses U.S. security concerns while being ŌĆ£fair for the Chinese.ŌĆØ

Why has TikTok remained available?

Spurred by fears that the Chinese government could gain access to TikTok usersŌĆÖ personal data, Congress overwhelmingly passed the ban in April 2024. The law prohibits the distribution of TikTok as long as it has ownership based in a country designated as a ŌĆ£foreign adversary.ŌĆØ

The text of the law did give the president the ability to grant a ŌĆ£1-time extension of not more than 90 daysŌĆØ before enforcing the ban ŌĆō if there has been ŌĆ£significant progressŌĆØ on divesting the app from its Chinese owner. The president must also certify this progress to Congress.

On April 4 ŌĆō when the original extension was set to expire ŌĆō Mr. Trump announced he would allow TikTok to keep running for another 75 days, exceeding the 90-day limit set by Congress. He passed a third extension in June, set to expire Sept. 17.

TikTok has seen several wealthy bidders in the interim, including companies like Amazon and Oracle. U.S. government officials have twice indicated that TikTok was close to having a buyer, only to have negotiations with the Chinese government fizzle out.

In late July, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick said in an interview on CNBC that TikTok would go dark in September if China didnŌĆÖt give the U.S. more control over the app by the next deadline. On Aug. 19, however, the White House launched its own TikTok account. The following day, the Chinese Communist Party published an editorial in which they expressed hope that Mr. Trump would extend his nonenforcement of the ban indefinitely.

Can the president ignore a law passed by Congress?

After President Joe Biden signed the TikTok ban into law in 2024, TikTok sued the federal government. The case went to the Supreme Court, and all nine members upheld the ban as constitutional.

When Mr. Trump ordered the second extension of the ban in April, Attorney General Pam Bondi wrote to executives of technology companies like Apple, saying the companies would not be held liable for distributing the app.

Ms. Bondi also said Mr. Trump had decided an abrupt shutdown of TikTok would interfere with the presidentŌĆÖs responsibilities over national security and foreign policy. In other words, she asserted that the president had the prerogative to nullify the lawŌĆÖs effects.

In March, several Democratic members of Congress ŌĆō who opposed the TikTok ban ŌĆō wrote to express their concern that the administration was ŌĆ£ignoring the requirements in the law.ŌĆØ A few Republican members have also expressed discontent, with Sen. Chuck Grassley telling reporters in June that he wanted to ŌĆ£know that the Congress isnŌĆÖt being played.ŌĆØ

Daniel Farber, the author of ŌĆ£Contested Ground: How To Understand the Limits of Presidential Power,ŌĆØ says CongressŌĆÖ ability to push back on this is limited. One avenue members could take would be to try to coerce Mr. Trump by refusing to confirm his appointees or to fund something he wants until he enforces the law.

However, there appears to be little political will in Congress to take direct action to try and enforce the ban.

What does delayed enforcement mean for the balance of powers?

Presidents are sometimes able to exercise legal discretion about which laws to enforce, says Alan Rozenshtein, a professor at the University of Minnesota Law School. ThatŌĆÖs in the same way that a police officer might decide not to pull someone over for going slightly over the speed limit.

But according to Ms. BondiŌĆÖs letters, Mr. Trump is not making a claim about discretion. Instead, she told companies they had made ŌĆ£no violation of the Act.ŌĆØ In other words, the administration wasnŌĆÖt just going to look the other way if technology companies distributed TikTok ŌĆō it openly asserted that the companies werenŌĆÖt breaking the law.

Mr. Farber says thatŌĆÖs a critical distinction.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs true that the president has the right to prioritize laws, but that doesnŌĆÖt mean that he can simply decide that he doesnŌĆÖt like some laws and is not going to enforce them at all,ŌĆØ he says.

There is a theoretical basis for the administrationŌĆÖs argument that it doesnŌĆÖt have to enforce a law it says will interfere with the presidentŌĆÖs constitutional responsibilities, says Mr. Rozenshtein.

For example, Congress canŌĆÖt pass a law saying the president is not the commander in chief (as the Constitution explicitly states he is). A Supreme Court case during the Obama administration said the president didnŌĆÖt have to follow a law of Congress that wouldŌĆÖve required him to recognize Jerusalem as part of Israel.

But according to Mr. Rozenshtein, Mr. TrumpŌĆÖs claim that he can overrule a TikTok ban passed by Congress because it involves national security takes that argument to an unworkable level.

ŌĆ£By that logic, almost anything that had any relation to foreign affairs or other countries could interfere with the presidentŌĆÖs constitutional powers,ŌĆØ he says.

And he doesnŌĆÖt think the fact that Mr. Trump reached a deal changes anything.

ŌĆ£You canŌĆÖt pick and choose,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£You canŌĆÖt say, IŌĆÖm going to let the president disobey the laws only when it will lead to a good outcome.ŌĆØ