Copyright Newsweek

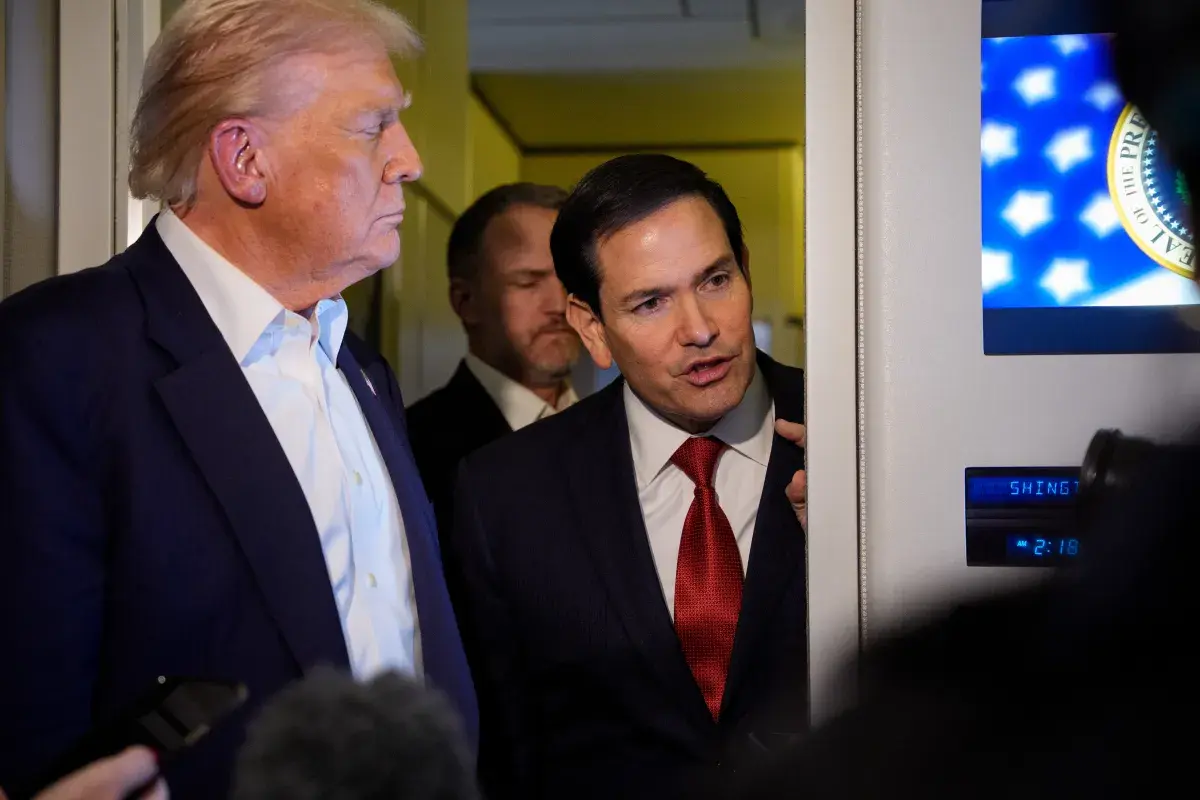

Nine months into Donald Trump’s second term, Latin America has become a central focus of U.S. foreign policy. The administration has shifted away from traditional development aid and diplomatic forums, opting instead for a strategy centered on tariffs, military pressure and bilateral political alignment. At the center of the effort is Secretary of State Marco Rubio, whose familiarity with regional politics has helped push forward a series of high-profile initiatives—from security operations to trade negotiations and visa actions. A January executive order declared drug cartels foreign terrorist organizations, enabling the U.S. military to strike suspected trafficking networks by force. Naval deployments and missile strikes along the Caribbean and northern South America soon followed. On Tuesday, four strikes in the eastern Pacific Ocean killed 14 people and left one survivor in the deadliest single day since the Trump administration began its campaign. U.S. Representative María Elvira Salazar, a Florida Republican and one of the administration’s most outspoken defenders, said Trump’s approach marked a long-overdue shift. “The Trump administration is doing exactly what it needs to do — to take out of power an illegitimate president, someone who stole the elections last year after promising to abide by the Barbados Accord,” she told Newsweek. “Thanks to Trump, who has the fortitude and courage to do what’s right for the United States — stopping the flow of drugs coming from Venezuela, which has become a launching pad for Colombian cocaine. So I commend him for doing that,” she added. The operations, which have resulted in dozens of deaths, have drawn sharp responses from both Republican and Democratic lawmakers as well as international leaders. Former Colombian President Ernesto Samper (1994–1998) told Newsweek that the strategy is deeply concerning. “The issue is the way it’s being done—violating international law and maritime conventions,” Samper, a center-left politician, said. “These are practically extrajudicial killings of crew members aboard small vessels.” Milei’s Bet Pays Off In contrast to the diplomatic standoffs unfolding in the Caribbean, Argentina has emerged as one of the Trump administration’s closest allies in the region—and a major recipient of U.S. support. Libertarian President Javier Milei secured a decisive midterm victory on Sunday, just weeks after receiving a $20 billion U.S.-backed bailout designed to shore up the Argentine peso and stabilize investor confidence. The win strengthens Milei’s ability to pass sweeping economic reforms, including austerity measures and deregulation policies long favored by Washington. It also validates a new Trump-era formula: align ideologically, and reap the benefits. “It was about time the United States paid attention to its closest neighbors,” Salazar told Newsweek. “From Tierra del Fuego to Tijuana and El Paso, we share a hemisphere. We must focus on our backyard—our allies and our partners. The Western Hemisphere should be in the hands of Americans, not our enemies.” The high-stakes nature of the midterms was no secret. In the lead-up to the vote, Trump tied future financial support to Milei’s political survival, telling aides, “If he doesn’t win, we’re gone.” U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, who framed the bailout as an “economic bridge with our allies,” said the U.S. was determined to avoid “another failed state in Latin America.” The deal sparked political controversy at home, with critics accusing Trump of using taxpayer money to underwrite a risky ideological gamble. But inside Argentina, it became a political lifeline. After a string of electoral setbacks and approval ratings that had dipped below 40 percent, Milei’s party clawed back momentum with a message of U.S.-backed stability. “Milei is an example that democracy and the market economy—free from socialism and corruption—are the true path to prosperity,” Salazar said. Now, Milei’s government is preparing to expand economic ties with Washington. Benjamin Gedan, director of the Latin America Program at the Stimson Center, said the partnership is already shaping Argentina’s foreign policy orientation. “Following the U.S. bailout, the two governments are now inseparable,” he told Newsweek. “It remains to be seen how the U.S. uses its leverage—whether to press for opportunities for U.S. mining companies or to drive a wedge between Buenos Aires and Beijing.” Though Milei has publicly embraced anti-China rhetoric, including vows to avoid deals with “communists and murderers,” his government still maintains critical financial arrangements with Beijing, including a standing currency swap with the People’s Bank of China. That tension between ideology and pragmatism could test the durability of the U.S.-Argentinian alignment. Gedan noted that the midterm results are a turning point. “For Washington, Milei’s success signals an opportunity to codify reforms that are harder to reverse under a future Peronist government,” he said. A Divided Hemisphere Elsewhere, the administration’s tone has turned sharply confrontational. In January, Colombian President Gustavo Petro refused to accept U.S. deportation flights. Within hours, Washington threatened tariffs, suspended consular services and tightened inspections on Colombian exports. Petro quickly reversed course, offering to send his own presidential plane to collect the deportees. By late September, tensions had escalated. The U.S. revoked Petro’s visa after he urged American troops at a pro-Palestinian rally in New York to disobey orders. Weeks later, amid missile strikes in the Caribbean, Petro accused Washington of killing two Colombian fishermen. On October 24, the Treasury Department sanctioned Petro, his wife and several close allies, alleging ties to drug trafficking—claims Trump amplified by calling him a “drug kingpin.” Salazar said the breakdown was self-inflicted. “President Petro cannot insult the President of the United States by going on the streets of New York and telling the troops not to follow what the Commander in Chief orders,” she said. Samper offered a starkly different view: “This conduct would be unlawful even if the administration were correct in every instance about its smuggling allegations,” he said. “We’re returning to that violent, autocratic past that defined U.S.–Latin American relations.” While Colombia and Venezuela have borne the brunt of Washington’s ire, Panama was the first to feel the shock early in Trump’s second term. Days after returning to the White House, the administration demanded U.S. oversight of the Panama Canal, citing growing Chinese influence. Rubio made his first foreign trip as secretary of state there, meeting President José Raúl Mulino and touring the Miraflores Locks. By the end of January, Panama had canceled its Belt and Road infrastructure agreement with China. Michael Shifter, former president of the Inter-American Dialogue, described the administration’s approach as “aggressive but erratic.” He told Newsweek: “It’s hard to deny that the Trump administration is doing more in Latin America than any U.S. government this century. Yet it’s equally hard to discern a coherent plan.” Inside Washington, Rubio has earned praise for his command of regional affairs. Salazar called him indispensable: “He’s doing a great job—not only in the Middle East but also in Latin America. We must applaud him because he knows the region and shares that knowledge with the White House.” As U.S. military deployments expand across the Caribbean, many Latin Americans are rallying behind what they call the Trump Doctrine. Among the supporters are 2025 Nobel Peace Prize winner María Corina Machado—Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro’s main rival—and former Colombian President Álvaro Uribe. Yet others warn the strategy could backfire. In Brazil, Trump’s public standoff with President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva boosted the leftist leader’s approval ratings and emboldened him to seek reelection next year. “This kind of heavy-handed diplomacy only fuels the anti-American sentiment that has long simmered in Latin America,” Samper said. “If history teaches us anything, it’s that interventionism breeds resistance, not allegiance.”