Copyright Anchorage Daily News

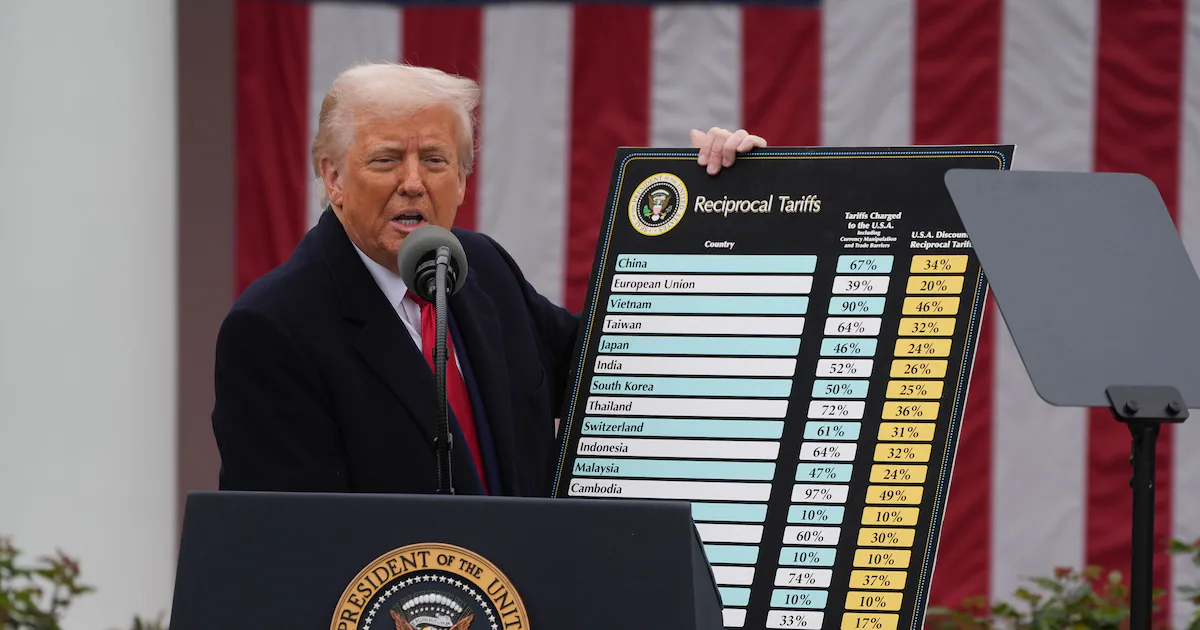

President Donald Trump is used to battles at the Supreme Court against liberal advocacy groups, but Wednesday’s high-stakes argument over his tariff policy features a very different foe - a legal center funded without public disclosure by some of the country’s wealthiest conservatives. The cases on which the Supreme Court is scheduled to hear oral arguments were brought by small businesses, which argue that Trump’s tariffs have harmed them by raising their costs. Standing behind them, however - and paying for some of the high-priced legal talent - is the Liberty Justice Center, a nonprofit group with a libertarian-leaning agenda that has previously challenged public-sector unions and sued to prevent the ban on TikTok from taking effect. Liberty Justice Center does not disclose the names of its donors, but a Washington Post analysis of tax filings found that since 2020, it has received money from Donors Trust, the Walton Family Foundation and the Bradley Foundation, all of which have been prominent conservative donors. Donors Trust is a fund that receives money from wealthy donors whose identities are not disclosed and steers it toward conservative causes. The group has frequently backed organizations associated with Federalist Society co-Chairman Leonard Leo, who counseled Trump on judicial picks during his first presidential term, but whom Trump denounced in May, in part because of the tariff case. Liberty Justice Center is also listed as a national partner of the State Policy Network, a network of conservative nonprofit organizations with links to Charles and David Koch that also receives funding from Donors Trust. Some of the most prominent groups and scholars associated with the conservative movement have sided against Trump in the tariff lawsuit, highlighting how import taxes have emerged as one of the clearest fault lines between the president’s MAGA base and the free-market groups that defined Republican politics before Trump. Filings in the case reflect that split: Prominent conservative economists, lawyers and judges have submitted briefs backing the businesses challenging the tariffs. One was signed by 31 former judges appointed by Presidents Ronald M. Reagan, George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush. The Chamber of Commerce, which was aligned with the Republican Party for decades before Trump, also filed a brief supporting the companies, as did the conservative Washington Legal Foundation and experts from groups widely viewed as right of center, including the American Enterprise Institute, the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and the Cato Institute. On the other side, think tanks and legal groups that have played a role in shaping Trump’s policies, including the America First Policy Institute and America First Legal Foundation, have supported the administration’s position. America First Legal Foundation was co-founded by Stephen Miller, now Trump’s deputy chief of staff. At issue in the case are the sweeping import taxes Trump has levied against scores of other countries. He claims authority for those tariffs under an economic emergency law that Congress passed in 1977. The statute, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), does not mention tariffs. It does give presidents the authority to “regulate” international commerce in response to an emergency. Trump asserts that the nation’s long-standing trade deficit constitutes an emergency and that the power to regulate under the emergency law includes the power to tax. Businesses have paid the federal government about $90 billion in tariffs implemented through emergency powers as of late September, according to data from U.S. Customs and Border Protection. If Trump loses, the federal government may have to refund that money to companies, worsening the federal deficit. Beyond the immediate financial impact, a loss on tariffs would be a huge blow to Trump’s economic agenda. The president has leveraged the levies as a tool of economic coercion in trade and defense-spending negotiations. He has also used them to punish countries against which he has grievances, including his decision late last month to slap higher taxes on Canadian imports after the province of Ontario aired a television ad that featured excerpts from a 1987 radio address in which Reagan criticized tariffs. “If a President is not allowed to use Tariffs, we will be at a major disadvantage against all other Countries throughout the World,” Trump said in a social media post over the weekend. “If a President was not able to quickly and nimbly use the power of Tariffs, we would be defenseless, leading perhaps even to the ruination of our Nation.” Last month, Trump said he planned to personally attend the court argument on Wednesday, which would have put him in the uncommon position of sitting quietly for hours while the spotlight focused on others. Over the weekend, though, Trump said he would not attend. His opponents say the tariffs are illegal. The Constitution specifically gives the power to levy taxes and “duties” to Congress. The president can only raise tariffs if Congress specifically authorizes it, the businesses challenging the tariffs argue. “The government contends that the President may impose tariffs on the American people whenever he wants, at any rate he wants, for any countries and products he wants, for as long as he wants - simply by declaring long-standing U.S. trade deficits a national ‘emergency,’” lawyers for the New York-based wine company VOS Selections, which is one of the challengers, wrote in their brief. “That is a breathtaking assertion of power” that goes far beyond what the Constitution allows, according to the brief, signed by three lawyers from Liberty Justice Center, along with two of the nation’s best-known lawyers - Neal Katyal, formerly the deputy solicitor general under President Barack Obama, and former federal appeals court judge Michael McConnell, a George W. Bush appointee. Without legal groups like the Liberty Justice Center, the small companies that challenged the tariffs would probably not be able to afford the legal costs, said Scott Lincicome, the vice president of general economics at the Cato Institute. “It is really expensive to fight government in court,” he said. “You need highly skilled lawyers to do it.” Trump’s tariffs are widely unpopular among voters. Sixty-five percent of respondents in a Washington Post-ABC News-Ipsos poll last week said they disapprove of the president’s tariffs on imported goods. Many conservatives are skeptical of Trump’s tariffs for dual reasons, said Lincicome. Tariffs are taxes, which conservatives historically have sought to limit, he said. Traditionally, he added, conservatives have been skeptical of executive power and delegations of congressional power to the executive branch. Big businesses, however, have largely remained silent on Trump’s tariffs. No major companies filed briefs supporting the challenge in the Supreme Court. Instead, they have sought to lobby the president and top administration officials for exceptions to the tariffs, in some cases winning large benefits as a result. Businesses and Wall Street are carefully watching Wednesday’s case, which could have a significant impact on prices for consumers. Though Trump often says China and other countries are paying the tariffs, they are paid by importers when goods arrive in ports in the United States. Companies have passed some of those costs on to consumers buying their products, although some are waiting to adjust their prices until the Supreme Court resolves the legal uncertainty around the levies. Jeffrey M. Schwab, the Liberty Justice Center’s senior counsel and interim director of litigation, said in an interview that the case is “not about partisan politics” and reflects the organization’s mission of combating government overreach. Liberty Justice Center is “very protective” of its donors, but they include a wide range of people and groups, Schwab said. “It’s not really about stopping the president’s signature policy,” Schwab said. “It’s about keeping the president’s power within the constitutional parameters that have been set.” Schwab said none of the donors identified by The Post specifically contributed to the tariff lawsuit. Some, however, made contributions intended to fund the organization’s general operations and litigation program, their filings show. Opposition to tariffs from some conservatives has angered Trump. Shortly after a lower court ruled against the tariffs in May, Trump went on the offensive in a post on Truth Social. He called Leo a “sleazebag” and accused the Federalist Society of giving him “bad advice” on what judges to appoint when he was new to Washington in his first term. The White House on Monday said the tariffs are part of Trump’s plan to restore prosperity by eliminating trade policies that left Americans behind. “The Administration is delivering on this pledge with what works: from traditional free-market policies like deregulation and working-class tax cuts to tariffs that are putting an end to lopsided ‘free’ trade arrangements,” White House spokesman Kush Desai said in a statement. The legal fight has highlighted the broader division among Republicans over tariffs. Trump has a tighter grip on the party than ever before, but tariffs are one issue where cracks in support have appeared. Some of his most prominent supporters in Congress and the business world criticized the rollout of his tariffs in April, which tanked the stock and bond markets until Trump backed off his initial announcement. Last week, four Republicans joined Democrats in the Senate to pass resolutions that would nullify some of the national emergencies that Trump has declared to justify the import taxes. The move is likely symbolic because the House has no plans to take up the matter. The divisions among conservatives have contributed to the uncertainty over how the Supreme Court may rule. Three of the nine justices on the Supreme Court were appointed by Trump, and in the first nine months of Trump’s second term, the court has largely ruled to expand his powers. But several of the lower-court judges who ruled against Trump on the tariff issue were also his appointees. “I think it will be close,” said Stan Veuger, a senior fellow in economic policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute who organized a brief written by economists on behalf of the companies. “Some of the Republican-appointed justices will be hesitant to strike down one of the president’s signature economic policies. I’m not confident all of them will vote to strike down tariffs, even though I think they should.”