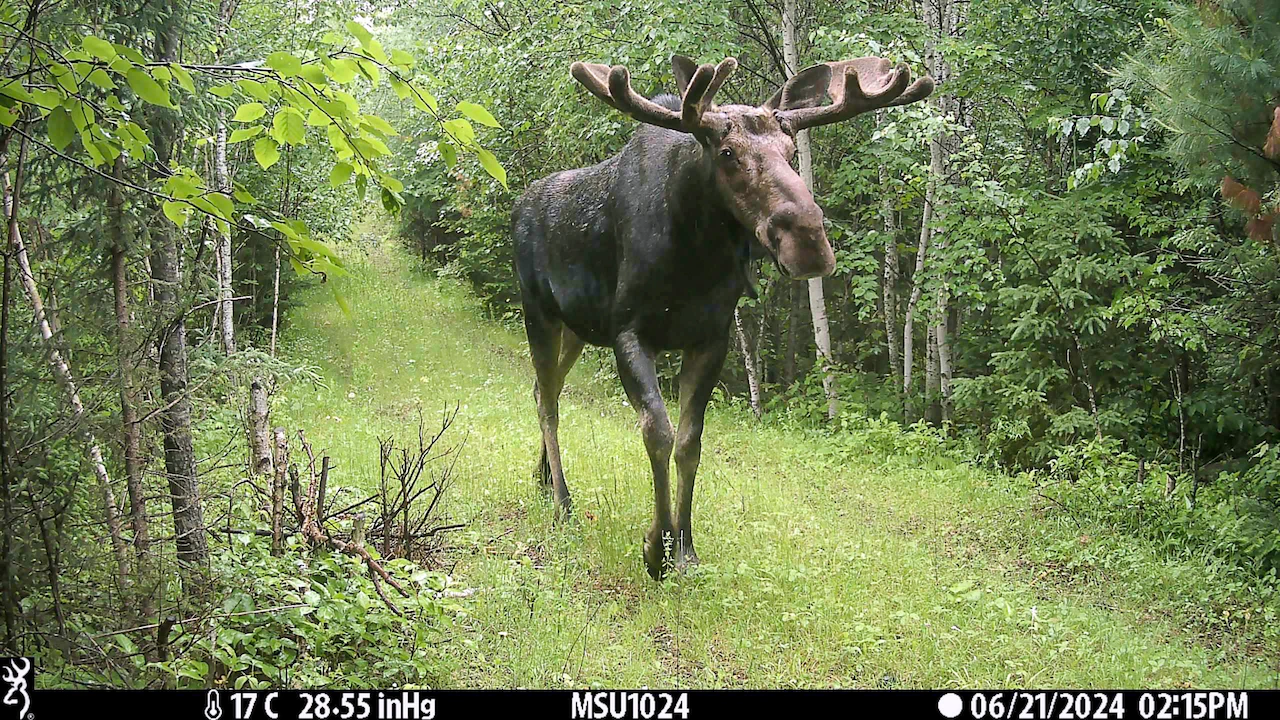

Copyright M Live Michigan

MICHIGAMME HIGHLANDS, MI - Michigan’s moose are on the move - and some of these huge animals are providing eyebrow-raising insights. The DNR biologists and researchers who are wading into their first few seasons of a multi-year study designed to track and better understand Michigan’s moose population in the Upper Peninsula are sharing some pretty cool details from what GPS tracking collar data is showing. Earlier this year, 20 moose of varying ages in the western U.P. - from young calves to big bulls - were fitted with radio collars around their necks as part of this study. Researchers are tracking their real-time movements, seeing how many babies are being born, and in the case of deaths, finding out what killed them. Here are a couple highlights from the research team: Big Travelers “GPS data from the collars has given researchers a close look at how moose behave during the summer calving season and the September breeding season,” DNR researchers said in reporting their findings. Tracking data showed a cow moose with twin calves moved north this summer, getting all the way up into the forests of the Keweenaw Peninsula. The GPS-plotted map above shows the color-coded paths of the three moose, and that they didn’t stay together as summer turned to fall. One of the twins stayed in the Keweenaw area while the mother moose and her other calf walked south, then split up. Researchers say this separation is common for moose families as the calves get older. “We’re seeing expanded movement patterns that reflect the seasonal shift as moose leave their northern summer range and head south for winter,” the DNR staff said. “We hope you find this data as interesting as our biologists do as this collaborative study continues.” Looking for Love One of the bull moose that researchers collared in mid-February has given the team a deeper look at how some moose behave during the fall breeding season. As the September rut approached, this big guy was seen traveling a long way outside his typical range during his search for some willing female moose friends. “During this time, bulls move more frequently in search of cows to mate with,” DNR staff said. “Unlike some western populations that form harems, Michigan’s moose are more likely to move from cow to cow, tending individual females rather than guarding a group. “In the past, we relied mainly on radio-collar locations, which offered only snapshots of movement. With GPS technology providing continuous data, we can now map breeding home ranges in far greater detail and learn how bulls move across the landscape to find mates.” By the Numbers At the end of September, 17 of the 20 collared moose remained as part of the study. From the DNR data: Collared adult males: 5 of 5 alive. Collared adult females: 9 of 10 alive. Collared calves (yearlings): 3 of 5 alive. Newborn calves (born to collared females): 8 of 11 alive. The latest moose population results show an estimated dip in the numbers in the core survey area. The aerial surveys are done every two years by the DNR and tribal biologists. This year’s survey estimated around 300 moose, down from 426 in the core survey area in 2023. “This change may reflect habitat shifts or moose dispersing outside the traditional survey area – similar to what researchers are seeing with the GPS collared moose." While the GPS tracking study is focusing on the moose in the western half of the U.P., there is a smaller moose population on the eastern side of the Upper Peninsula. There, they roam over Alger, Luce, Schoolcraft and Chippewa counties, the DNR said. The study is expected to continue through 2028 and involve 60 collared moose. Numbers remain stagnant While the big animals with their paddle-like antlers once roamed across Michigan, by the early 1900s their numbers had grown sparse and were limited to the Upper Peninsula. An attempt to reintroduce them in the 1930s went nowhere, according to the DNR. It took the famous “Moose Lift” of the 1980s for any real population to take hold. This involved fitting 59 of these big animals into carrying slings and airlifting them by helicopter, then transporting them by truck from the Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario, Canada, to the U.P.‘s Marquette County. The goal was to have a 1,000-strong moose population in that area by 2000. But now the latest numbers show around a third of what DNR researchers thought we’d have by now. READ MORE ABOUT MICHIGAN’S MOOSE: 60 Michigan moose died in vehicle collisions on U.P. highways in 4 years Island Moose A separate moose population lives on Isle Royale in the northern reaches of Lake Superior. There were an estimated 840 moose living on the island archipelago when surveyed last year. They live in a national park wilderness and are not part of this study.