Copyright The Atlantic

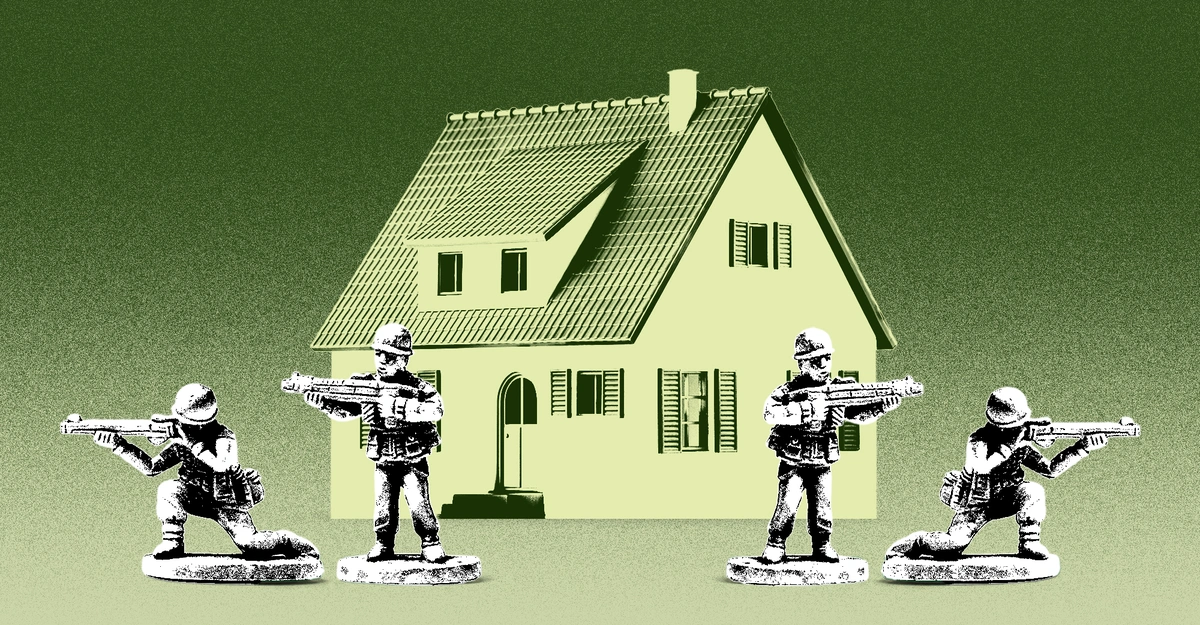

The former White House adviser Katie Miller—mother of three young children, and wife of the presidential right-hand man Stephen—walked out of her front door one Thursday morning last month and was confronted by a woman she did not know. When she told this story on Fox News, she described the encounter as a protest that crossed a line. The stranger had told Miller: “I’m watching you,” she said. This was the day after Charlie Kirk’s assassination. It also wasn’t anything new. For weeks before Kirk’s death, activists had been protesting the Millers’ presence in north Arlington, Virginia. Someone had put up wanted posters in their neighborhood with their home address, denouncing Stephen as a Nazi who had committed “crimes against humanity.” A group called Arlington Neighbors United for Humanity warned in an Instagram post: “Your efforts to dismantle our democracy and destroy our social safety net will not be tolerated here.” The local protest became a backdrop to the Trump administration’s response to Kirk’s killing. When Miller, the architect of that response who is known for his inflammatory political rhetoric, announced a legal crackdown on liberal groups, he singled out the tactics that had victimized his family—what he called “organized campaigns of dehumanization, vilification, posting peoples’ addresses.” Stephen Miller soon joined a growing list of senior Trump-administration political appointees—at least six by our count—living in Washington-area military housing, where they are shielded not just from potential violence but also from protest. It is an ominous marker of the nation’s polarization, to which the Trump administration has itself contributed, that some of those top public servants have felt a need to separate themselves from the public. These civilian officials can now depend on the U.S. military to augment their personal security. But so many have made the move that they are now straining the availability of housing for the nation’s top uniformed officers. Kristi Noem, the Homeland Security secretary, moved out of her D.C. apartment building and into the home designated for the Coast Guard commandant on Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling, across the river from the capital, after the Daily Mail described where she lived. Both Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth live on “Generals’ Row” at Fort McNair, an Army enclave along the Anacostia River, according to officials from the State and Defense Departments. (Rubio spent one recent evening assembling furniture that had been delivered to the house that day.) Although most Cabinet-level officials live in private houses, there is precedent for senior national-security officials, including the defense secretary, to rent homes on bases for security or convenience. Army Secretary Dan Driscoll, whose family is in Washington only part-time, now shares a home on Joint Base Myer-Henderson Hall, a picturesque site next to Arlington National Cemetery. His roommate is another senior political appointee to the Army. (When Driscoll moved in, his washing machine wasn’t working, so for the first few weeks of his stay on base, he lugged his laundry over to the home of the Army chief of staff, General Randy George.) Another senior White House official, whom The Atlantic is not naming because of security concerns related to a specific foreign threat, also vacated a private home for a military installation after Kirk’s murder. In that case, security officials urged the official to relocate to military housing, according to people briefed on the move, who like many others who spoke with us for this story were not authorized to do so publicly. So many senior officials have requested housing that some are now encountering a familiar D.C. problem: inadequate supply. When Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard’s team inquired earlier in Donald Trump’s second term about her moving onto McNair, it didn’t work out for space reasons, a former official told us. There are scattered examples from previous administrations of Cabinet members residing on bases. Both Robert Gates, defense secretary under presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, and Jim Mattis, Trump’s first Pentagon chief, lived in Navy housing at the Potomac Hill annex, a secure compound near the State Department. Mike Pompeo, CIA director and secretary of state during Trump’s first term, lived at Joint Base Myer-Henderson Hall. The grand homes they occupied, some of which date back more than a century, offer officials an additional layer of security and ample space for official entertaining. But there is no record of so many political appointees living on military installations. The shift adds to the blurring of traditional boundaries between the civilian and military worlds. Trump has made the military a far more visible element of domestic politics, deploying National Guard forces to Washington, Los Angeles, and other cities run by Democrats. He has decreed that those cities should be used as “training grounds” in the battle against the “enemy within.” Adria Lawrence, an associate professor of international studies and political science at John Hopkins University, told us that housing political advisers on bases sends a problematic message. “In a robust democracy, what you want is the military to be for the defense of the country as a whole and not just one party,” Lawrence told us. But the threat assessment has also changed in recent years. Trump has survived two attempted assassinations; Iran has stepped up its efforts to kill federal officials; and political violence—such as the June shooting of two Democratic Minnesota lawmakers, the murder of Kirk in September, and the shooting at a Texas immigration facility two weeks later—is a real danger. The result is straining the stock of homes typically allotted to senior uniformed officers on Washington-area bases. Some of those homes, designed for three- and four-star generals, lack sufficient bedrooms for families with young children. Many have lead-abatement issues and require significant repair. The Army notified Congress in January that it planned to spend more than $137,000 on repairs and upgrades to Hegseth’s McNair home before he moved in. Both Hegseth’s predecessor, Lloyd Austin, and Austin’s State Department counterpart, Antony Blinken, faced protesters at their northern-Virginia homes, which were not on bases. Gaza protesters who set up camp outside Blinken’s house, where he lived with his young children, spattered fake blood on cars as they passed by. Robert Pape, a political-science professor at the University of Chicago, told us that the threat of political violence is real for figures in both major parties. He noted that Trump has revoked the security details for several of his critics and adversaries, including former Vice President Kamala Harris and John Bolton, the former national security adviser from Trump’s first term who has been the target of an Iranian assassination plot. “The correct balance would be: Trump should stop canceling the security detail of former Biden officials,” said Pape, who is also the director of the university’s Chicago Project on Security and Threats. “The issue is both sides are under heightened threat; therefore the threat to both should be taken seriously.” In most cases, the civilian officials pay “fair market” rent for their base home, a formula determined by the military. Hegseth, in keeping with a 2008 law that aimed to make Gates’s Navy-owned housing arrangement more affordable, pays a rent equivalent to a general’s housing allowance plus 5 percent (in this case, totaling $4,655.70 a month). The moves, however, can also save the government money. In some cases, base living can reduce the cost of providing personal security to officials, one person familiar with the relocations told us, because protective teams do not need to rent a second location nearby as a staging area. Base living—in the unofficial Trump Green Zone—has also become something of a double-edged status symbol among Trump officials. No one wants to deal with threats; both the Millers and the unnamed senior official were not looking to leave their homes. But the secure housing does confer upon the recipient a certain sheen of importance that sets them apart from all of the other officials ferried about in armored black SUVs. Administration officials now find themselves vying for the largest houses, not unlike the behind-the-scenes maneuvering that has long played out among senior military officers. The isolation of living on a military base, at least for civilians, has also created a deeper division between Trump’s advisers and the metropolitan area where they govern. Trump-administration officials, who regularly mock the nation’s capital as a crime-ridden hellscape, now find themselves in a protected bubble, even farther removed from the city’s daily rhythms. And they are even less likely to encounter a diverse mix of voters—in their neighborhoods, on their playgrounds, in their favorite date-night haunts. After the Kirk assassination, the Trump administration designated antifa a domestic terrorist organization, even though there is no centralized antifa organization, no organizational ties have been established to Kirk’s alleged killer, and the category of domestic terrorist organization has no meaning in federal law. The identities of the activists behind the harassment campaign that helped persuade the Millers to leave their home have not been publicly disclosed. Arlington Neighbors United for Humanity—ANUFH, pronounced, they say, enough—has organized protests near the homes of Miller and Office of Management and Budget Director Russell Vought. Its website calls for “strategic, nonviolent action,” and its efforts appear to have stopped short of making any explicit threats of violence. (A representative of the group declined to comment, as did the Millers.) But the protests were designed to make the Miller family take notice. Stephen Miller has been an architect of Trump’s deportation policy, invoking a centuries-old law to send migrants to a Salvadoran prison and urging immigration-enforcement officers to aggressively find and arrest as many immigrants as possible. He regularly derides Democrats with inflammatory language, calling judicial rulings against the administration a “legal insurrection” and calling the Democratic Party “a domestic extremist organization.” “Will we let him live in our community in peace while he TERRORIZES children and families? Not a chance,” ANUFH captioned one Instagram post in July that shows a photograph of the Millers and their children. (The Millers have both posted family photos online that show their children’s faces.) Weeks later, the group took credit for covering the sidewalk near the Miller home with chalk messages such as Miller is preying on families, although it said in a post that it had spoken with Stephen Miller’s security beforehand to make sure that the group wasn’t violating any laws. Katie Miller responded with an Instagram post of her own, a video of the chalked words STEPHEN MILLER IS DESTROYING DEMOCRACY! being washed away with a hose. She argued in a subsequent appearance on Fox News that although the protesters may not be violent themselves, they were inciting the kind of violence that killed Kirk. “We will not back down. We will not cower in fear. We will double down. Always, For Charlie,” Katie Miller wrote, echoing her husband’s rhetoric. “WE ARE PEACEFULLY RESISTING TYRANNY,” ANUFH responded in a post. “GUNS KILL PEOPLE. CHALK SCARES FASCISTS.” Earlier this month, the Millers put their six-bedroom north Arlington home on the market for $3.75 million. The listing promised “a rare blend of seclusion, sophistication, and striking design.” Nancy A. Youssef and Vivian Salama contributed reporting.