By Serish Nanisetti

Copyright thehindu

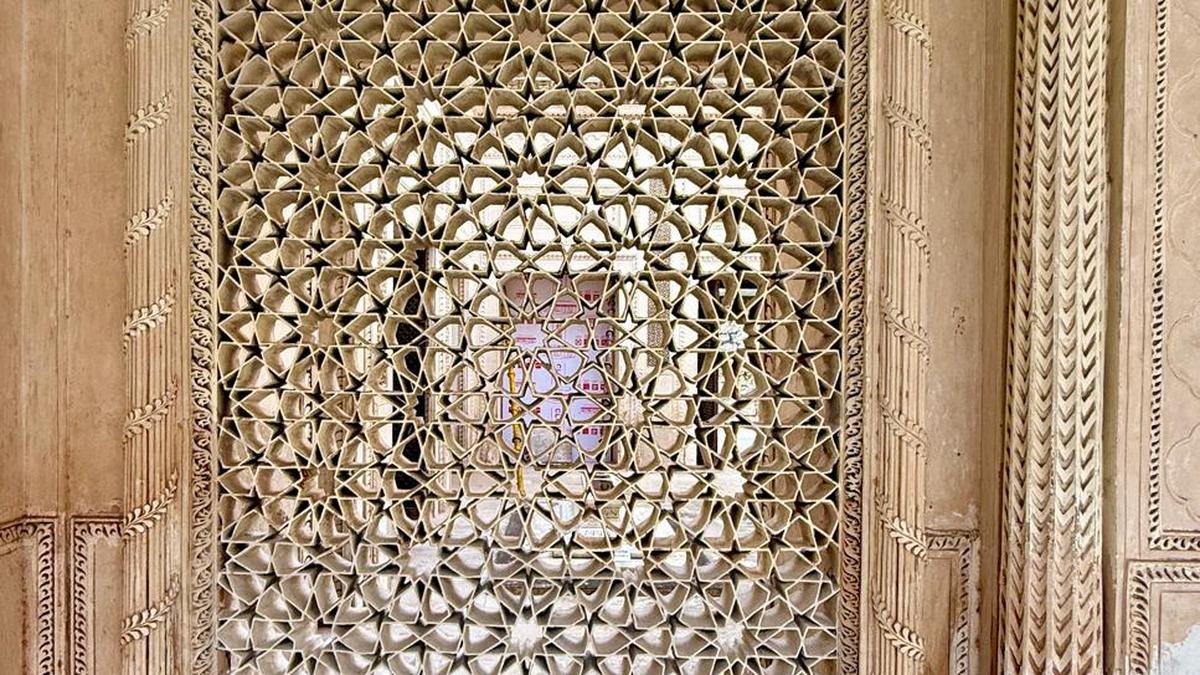

The loudest sound at the Paigah Tombs is the shrill whine of a mechanical cutter slicing 2 mm thick terracotta tiles into small pieces. These pieces are then fitted into what resembles a jigsaw puzzle, guided by a design cut into a laminated board.

“This is magical work. Our restoration effort begins with what looks like assembling a house of cards. Then apply a finely-ground lime mortar,” CEO of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) Ratish Nanda says, which is carrying out the restoration work at the late 18th-century tombs complex.

The restoration is slow, delicate, and painstaking. Skilled craftsmen work to create a one-foot-high stack of lattice, which is left to dry for a week before the next one-foot section is added, covered with limestone, and again allowed to dry. “It took us four to five years to practice on working out a technique that would match the original work. Hats off to the craftsmen who did this originally,” says Mr. Nanda, visibly in awe of the exuberant architecture and design of the tomb complex.

“This is the ‘firma’ or tracing of the pattern of the design. First we draw it, then print it, and then the tiles are assembled into the pattern,” explains Sandeep Raj of the AKTC, who supervises work on the site. Around him, dozens of craftsmen bend and squint, carefully assembling tiles and applying fine lime mortar on the six main tombs arranged in a row.

Located metres away from defence facilities in Santoshnagar, and marked by a green arch, the site is the resting place of Paigah nobles who provided military muscle to the Nizams — rulers of Hyderabad from 1724 to 1948.

After decades of neglect, destruction, and encroachment, the tombs — renowned for incised plasterwork, surface ornamentation, and intricate marble carvings — are now being restored by the State government and the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, with funding from the U.S. State Department’s Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation.

The transformation has been dramatic. Once rundown, covered with graffiti, and riddled with holes in its delicate trelliswork, the site now dazzles with renewed splendour.

“The restoration of the historic Paigah Tombs highlights America’s role as a trusted partner of choice in conservation. As one of the largest AFCP grants in Telangana, this three-year initiative fosters collaboration between American and Indian institutions and demonstrates America’s respect for the value of history and heritage,” said a spokesperson of the U.S. Consulate in Hyderabad.

The earliest tomb on the site belongs to Abu’l Fateh Khan Tegh Jung, the first to receive the title from Nizam Ali Khan. The jali work on his tomb is only the beginning — the later tombs display a dramatic apogee of craftsmanship.

“Kal tak ho jayega (it will be ready by tomorrow),” says Eshwar, a craftsman working on the lime stucco overhang of a richly decorated arch. Another worker laments modern visitors’ careless behaviour: “We are making them, people clicking selfies are breaking them as they handle it roughly. These lasted so long because there were no selfie-takers earlier.”

While the stucco decoration and intricate jalis command attention, the biggest challenge for the conservation team lay in the leaking roofs, which threatened the structures. These were cleaned and restored using cured limestone mortar with appropriate drainage facilities. The tombs were designed with a clever open-to-sky grave and an arcaded walkway for access, a feature that has endured over centuries.

As the restoration nears completion, the Paigah Tombs are poised to become one of the standout attractions on Hyderabad’s tourist map.