EBEYE, Marshall Islands – Every Friday on this tiny Pacific isle, Korab Lanwe does his rounds. The people he visits have severely swollen, discolored legs, or wounds that won’t heal, or have lost a limb. They are so ill they cannot leave their homes of plywood and metal sheets. Lanwe inquires if they are taking their meds and checks their blood pressure. The result is often grim.

Lanwe, who operates from an office with a rotting ceiling and boarded-up windows, is Ebeye’s diabetes coordinator. His homebound patients are in the advanced stages of a disease that plagues at least a third of the roughly 10,000 residents of Ebeye – a strip of sand 60 football fields in size, located 20 minutes by boat from an American base that has become pivotal in the U.S. showdown with China.

Despite Lanwe’s efforts, his rudimentary hospital can do little as his patients’ limbs turn gangrenous and their kidneys fail. There are no dialysis machines for them, nor a prosthetics lab to replace the legs that surgeons amputate. Many people on Ebeye don’t live beyond their 50s.

“It scares me. I’m basically thinking about my kids. Their future, the island’s future,” says the 42-year-old Lanwe. “We might be losing our people.”

Every morning, not far from his office, residents who are able to work wait at the island’s harbor, from which a U.S. Army ferry will take them about three miles south to Kwajalein – an island 10 times Ebeye’s size. There, residents of Ebeye serve as laborers while the Americans test U.S. missiles and monitor Chinese rocket launches.

The 1,300 U.S. soldiers and contractors on Kwajalein base enjoy air-conditioned homes, soaring palm trees, public swimming pools, a country club, a nine-hole golf course and a bowling alley. There is also a hospital and a veterinary clinic, according to military orientation materials. The Americans call the island “Almost Heaven.”

The contrast between life on Ebeye and Kwajalein is not lost on Kalani Kaneko. A U.S. Army veteran whose wife is from Ebeye, Kaneko is the foreign minister for the Marshall Islands, the sprawling archipelago in the central Pacific that includes Ebeye.

“Living conditions between Ebeye and Kwajalein, it’s day and night,” Kaneko said. As a veteran, he later added, “I’m very embarrassed. Especially, how can I tell my kids and grandkids?”

Interviews with more than 40 residents on Ebeye and eight Marshallese officials, as well as a review of American military documents, reveal the extent of a humanitarian crisis in a community the U.S. created in the 1950s and whose labor it depends on to run a base it calls a “vital national asset.”

Diabetes is just one of Ebeye’s problems. Local fish, which many residents rely on to supplement their low-nutrition diets, are contaminated. Starting in 2008, a series of U.S. military reports warned about poisonous pollutants flowing from the base into the ocean. And, while not drawing a direct connection to that toxic run-off, one report from 2017 found that levels of arsenic and heavy chemicals in fish around Ebeye were so high that eating them posed “potentially unacceptable” risks.

The island is also regularly plagued by blackouts due to an aging power station. And almost half of local households told government surveyors in a 2021 census that they skipped meals due to lack of money.

The harsh living conditions on Ebeye could create an opening for China, as it tries to spread its influence across the Pacific.

“That’s the word we’ve received: They can offer more,” Kaneko said of the Chinese proposition during an interview in the Marshallese capital of Majuro. “They can fix our hospital, they can fix our ports, they can help create jobs.”

Kaneko, who like many Marshallese still holds deep affection for America, said he rejected the offer. But if the problems that plague places like Ebeye persist, he warned, a future Marshallese administration might be tempted to explore “what’s on the other side.”

Laura Stone, the U.S. ambassador to the Marshall Islands, told Reuters that Marshallese recognize the Chinese offers are “wildly overblown,” and that “the United States and its partners are really good, good partners, and that their future lies with the United States.”

China’s foreign ministry said in a statement it wasn’t “competing for influence with any other country in the Pacific island region” and that Pacific island nations “are not any country’s ‘backyard’.” Regarding Taiwan, the ministry said it was “not in the long-term interests” of Pacific island countries that still had diplomatic relations with Taipei to retain these ties, which go “against the tide of history.”

Beijing views Taiwan as part of China and has intensely lobbied other countries to sever diplomatic relations with Taipei. Taiwan’s government rejects China’s sovereignty claims, and says it has the right to forge ties with other countries.

Taiwan’s foreign ministry said China “has never abandoned its practice of using ‘cash-throwing diplomacy’ to infiltrate relevant island nations in the Pacific.” Beijing, it added, was working to “extend its influence deep into the Pacific region.”

Ebeye’s mayor didn’t respond to questions from Reuters and its traditional chief didn’t respond to interview requests. The U.S. State Department and Pentagon also didn’t respond to questions for this story.

‘BEING SLOWLY KILLED’

Lanwe started focusing on Ebeye’s diabetes epidemic over a decade ago, after his grandmother was diagnosed with the disease. She was one of the few able to afford to move to Honolulu for dialysis. Eventually, she decided to return home to die. It was too late. The night she decided to return, Lanwe said, she passed away in hospital.

Watching her waste away spurred him to train as a nurse. He wanted to make sure other family members didn’t suffer the same fate.

The Marshall Islands has one of the world’s highest rates of diabetes, according to the International Diabetes Federation. A 2021 study by University of Arkansas academics and Marshallese health officials attributed this to an enduring dependence on highly processed foods imported from the continental U.S. Many of these foods were widely distributed by U.S. officials after America conducted 67 nuclear tests around atolls north of Kwajalein between 1946 and 1958, stirring fear among Marshallese that local food was contaminated.

The country’s diabetes problem is worst on Ebeye, where a 2023 Marshallese government report found that at least 33% of residents have the disease. Locals say the crisis is driven by a lack of land and meager incomes. Almost all of Ebeye’s space is taken up by housing for its residents.

With no land to grow crops or keep livestock, locals depend on expensive imports carried by a twice-monthly barge from the U.S. In June, a cabbage from Ebeye’s main store cost about four times the amount a customer would pay at a Walmart in Texas.

The 1,000-odd Marshallese workers on Kwajalein earn an average of $22,000 a year, according to government data. Another 1,700 Ebeye residents have jobs, according to a review of figures in the 2021 census. These mostly pay less.

Many workers express gratitude for the jobs available on the base. But the island’s impoverishment has created a dependency on the cheap rice, frozen chicken and canned meat that drives the diabetes epidemic on Ebeye.

Residents are dying at an average age of 52, according to a Reuters analysis of records for the 330 deaths on the island between 2020 and 2024, which were provided by Ebeye hospital’s medical director.

Diabetes caused or contributed to at least 49% of those deaths, the records show. Like a 52-year-old diabetic who died from blood poisoning caused by a flesh-eating infection, to which diabetes made them more vulnerable. Or a 51-year-old diabetic who died of blood poisoning after developing gangrene in both feet.

By comparison, in 2021, 12% of Americans had diabetes and the disease caused or contributed to 12% of U.S. deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. American life expectancy in 2023 was 78 years.

The U.S. base receives fresh food each week by air. Most Marshallese cannot enter Kwajalein, which is a restricted military area, and the vast majority of the base’s Marshallese workers aren’t allowed to use its grocery store, where fresh fruit and vegetables are sold, according to 10 workers who spoke on condition of anonymity. They may buy goods from its food court, which – according to photos viewed by Reuters – hosts a Subway, a Burger King and a bakery with a few shelves of bananas and oranges.

Marshallese workers “are the backbone of our labor force,” Matthew Cannon, the base’s new commander who arrived in May, told Reuters. The conditions on Ebeye, he said, “cause me concern.”

But opening access to the grocery store “would triple or quadruple the amount of people that would go in there and the shelves would be difficult to keep stocked,” said Cannon.

Some locals expressed anger at their limited food options.

“I feel like we’re just being slowly killed,” said Abon Arelong, an Ebeye official, referring to the imported food on which residents largely rely.

During Lanwe’s home visits, his first stop is a trailer in Dumptown, an area nicknamed for its proximity to Ebeye’s trash heap. There, Bodin Corinth, a patient with one leg, sits inside a three-square-meter room, surrounded by her husband, a daughter and three grandchildren.

A trainee accompanying Lanwe begins checking Corinth’s blood. She lost her leg to diabetes six years ago, Lanwe explains, and is still waiting for a prosthesis, for which she must travel to another island. Corinth’s blood pressure level is high: 153/84. Lanwe reminds her to take her medication, then moves on.

His car radio plays the Armed Forces Network, one of two channels on Ebeye, which blares an NPR dispatch about the U.S. Supreme Court. Lanwe stops at the home of Winda Kaminaga, who lies inside on a wooden bedframe cushioned by thin cardboard strips.

Lanwe lifts Kaminaga’s right leg, swollen to twice its normal size. It has been like this for five years, she says. Lanwe prods her foot and asks if she feels anything. She shakes her head.

Kaminaga’s blood pressure is even higher than Corinth’s: 170/101. Her son works on Kwajalein and hasn’t had time to renew her medication, she explains. Lanwe promises to return with a refill. Previously, Kaminaga often spent time at church. Now, unable to walk more than a short distance, she can no longer attend.

DETERRING CHINA

The U.S. seized Kwajalein from Japan during World War Two. In 1951, the U.S. military relocated its inhabitants to sparsely populated Ebeye so that it could expand the base. Later, it also resettled people displaced by American missile testing elsewhere in the area on Ebeye, while the lure of jobs on Kwajalein drew thousands more. The U.S. “needed workers,” said Giff Johnson, the editor of the local newspaper. “That’s the magnet that makes Ebeye what it is.”

The Marshall Islands is one of three Pacific nations – along with Palau and Micronesia – previously administered by the U.S. All are technically independent, but treaties with the U.S. effectively give America control over the northern half of the Pacific Ocean, locking China’s military out of the region. In exchange, these island states get financial support on which they are heavily reliant and a promise of U.S. protection.

According to U.S. budget documents, the “unmatched instrumentation” on Kwajalein is a key element that makes “the nation’s space and missile operations possible.” The base hosts a monitoring array that the military describes as “the world’s most sophisticated suite of radar, optics, telemetry and scoring sensors.”

Among other things, the U.S. military uses that technology to test its missiles and interceptors, which regularly streak across the Pacific after launching from California or areas near the Kwajalein base.

According to a U.S. military factsheet, the base also provides “first visibility of most launches out of Euro-Asia,” making it an indispensable early warning system in the event China or Russia fired missiles at America.

That makes Kwajalein “one of the most valuable sites” for the U.S. military, says Courtney Stewart, deputy director of defense strategy at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute and a former Pentagon adviser on nuclear issues. It is “absolutely crucial” to deterring China.

U.S. budget documents show that the Army plans to spend at least $458 million on its Kwajalein operations in the 2026 financial year alone.

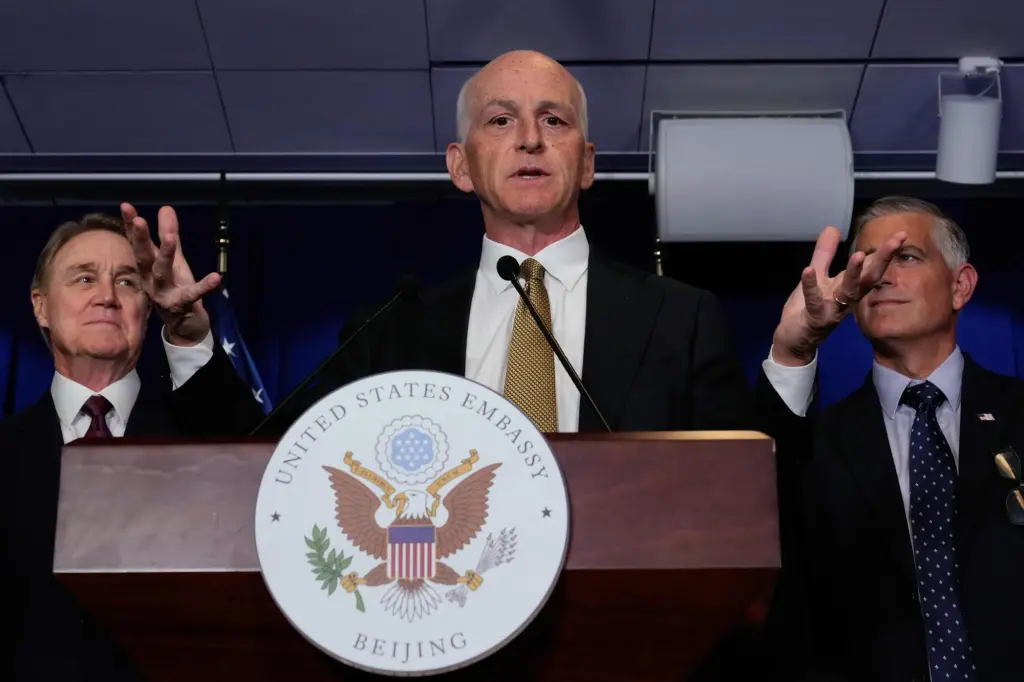

“We’re seeing China trying to exert influence in both overt and covert ways,” said Stone, the ambassador. “There are standing offers of investment that come from official Chinese institutional infrastructure, but they also have implied offers that you’ll get: The yuan will rain down on you in beautiful munificence.”

China’s foreign ministry said its assistance to Pacific island nations was “unconditional, unforced and without empty promises.”

For the Marshall Islands, the renewed treaty led to the $2.3 billion funding pledge, which includes the $132 million development fund for Ebeye.

In return for use of Kwajalein, the U.S. pays the island’s traditional leaders about $26 million annually in rent, some of which is shared with other residents on Ebeye, according to 2025 Marshallese budget documents. The U.S. also provides roughly $17 million in funding to local authorities on Ebeye each year.

Kaneko is thankful the treaty was renewed, but he’s also annoyed with the U.S. “They see the value of our region just because of the geopolitics,” he says.

‘YOU PICK YOUR POISON’

As a child, Calvin Juda’s favorite days were when his grandfather came home from working on Kwajalein and ushered him into his small boat to go fishing. Out on the water, his grandfather would tell him stories of watching Japanese troops as a scout for the Americans during the Second World War.

After a stint in the U.S., where he fell into drug dealing, then became a born-again Christian, Juda, 56, returned to Ebeye, where he works as the environmental health officer at the island’s hospital. He fishes to supplement the frozen chicken and rice that are staples for his 10-person household. On Ebeye, residents with fishing rods routinely speckle the lagoon shore.

But these waters contain an invisible danger. Studies by the U.S. Army Public Health Center since 2008 have found that the fish around Kwajalein Island have been contaminated by activities on the base. The 2017 study determined that reef fish around Ebeye have also been poisoned with arsenic and toxic fluids known as PCBs, which are used in electrical equipment: the same kinds of contaminants found in fish around the base. The study, though, didn’t draw a direct link to the base as the source of the contamination.

The 2017 study found that long-term consumption of Ebeye’s fish poses “potentially unacceptable” risks of cancer and damage to the nervous and reproductive systems.

The studies identified several sources of contamination on Kwajalein base, including run-off from sandblasting of vessels, leakage of electrical fluids into the ocean and waste run-off.

Marshallese workers fished at contaminated locations at the base until the mid-2010s, when the military enforced a fishing ban. No such ban has been enforced on Ebeye.

The U.S. is cleaning up its base. According to a 2024 Army planning document, “The main onshore potential contamination sources have been identified and, in some cases, abated or eliminated.” The document added that Kwajalein’s harbor remains “contaminated” with heavy metals, pesticides and PCBs.

In a 2014 report, military scientists recommended that the Army commission a study of the impact on Ebeye’s residents of consuming fish from contaminated areas. But Moriana Phillip, the Marshall Islands’ environmental regulator, says the Army ignored that recommendation, as well as her own requests for testing to identify the cause of Ebeye’s pollution.

“This has been one of the most difficult things to get the United States to discuss openly,” said Phillip. “It’s telling us that the United States is not taking us seriously.”

In a statement, the U.S. embassy to the Marshall Islands said it had not received any recent requests for further testing about the cause of fish contamination around Ebeye, but added that, “Upon receipt of a request to conduct additional studies, the U.S. Government will respond.”

Cannon, the base commander, said he hadn’t seen material documenting a connection between Kwajalein and Ebeye’s contamination. He said he was not familiar with the requests for a health impact study or further testing.

In the 2010s, the military organized information sessions on Ebeye to warn residents that fish around the U.S. base were contaminated. It also uploaded some reports, including the 2017 study showing contamination of fish around Ebeye, to a website. But that website is defunct, and there are no signs on Ebeye to warn residents about local contamination.

Marshallese officials said some pollution may come from Ebeye’s dump: an unlined trash heap that grew perilously high because the island had no incinerator.

In 2020, a report prepared for the Asian Development Bank by the Marshallese government noted that the “most efficient solution” would be to ship the waste to the incinerator at the U.S. base on Kwajalein. But, the report said, the military felt American funding to the Marshallese government “covers all their obligations, so the base is generally very reluctant to assist Ebeye.”

Cannon, the base commander, said he was unaware of such a request. The ADB has promised Ebeye funding for an incinerator.

Dixon Elleisha, who fishes from Ebeye’s wharf most nights, said he’d never heard that Ebeye’s fish might be contaminated. “I never have any worry, because the fish that are near land are safe,” he said. “I’ve been eating them since I was a young kid.”

Juda learned of the contamination risk around 2016 through his work as the island’s environmental health officer and suggested putting up warning signs. He said local leaders rejected the idea. “That is our main food,” he recalled them saying. “If we ban that place or restrict that place, are there any other options?”

Afterwards, Juda pushed out of mind concerns about the fish he feeds his three daughters and one-year-old son. If he stops fishing, he said, he will “end up eating other things like Spam.” And then he will “get sick” with diabetes.

A spokesperson for Hormel Foods, which makes Spam, said its products carried “clear nutritional information to help consumers make informed choices.”

Asked about locals’ reliance on fish that may be contaminated, David Paul, a senator for Ebeye and the Marshallese finance minister, said, “What’s the alternative? The alternative is we continue to eat processed food. Can I say: You pick your poison.”

‘HEIGHT OF ARROGANCE’

Ebeye’s infrastructure has improved since 2017, when Australia’s aid agency and the Asian Development Bank – with U.S. support – built a desalination plant so residents no longer had to travel to Kwajalein to get fresh water. They also repaired the island’s sewerage so that feces were no longer pumped directly into the lagoon.

America has funded a new school, as well as housing for some families it removed from nearby islands in the 1960s to make space for missile testing. Paul, the finance minister, said he is in the “exploratory stages” of negotiations with the ADB, World Bank and U.S. to build a new hospital.

Asked about the living conditions on Ebeye, Stone said the U.S. was providing new funds for the island. In terms of how they’re allocated, she said, that’s a decision for the Marshallese authorities, and it would be “the height of arrogance for the United States to come in and say exactly where they should be using the resources we provide.”

Harden Lelet, Ebeye’s town manager, said his island’s relationship with the U.S. was “very strong” and that “it really opens up a lot of opportunities.”

But Lanwe, the diabetes coordinator, says the island’s crises remain profound.

“Sometimes, I get angry. Sometimes I even criticize the leadership,” he said, referring to Ebeye’s politicians and Kwajalein’s commanders. He quickly added: “Just in my imagination.”

His hopes of keeping his family diabetes-free have been dashed. His aunt and two uncles now have the disease. Several years ago, his father began complaining of dizziness and hunger. When Lanwe ran tests, he discovered his father was diabetic, too.

“In that moment,” Lanwe said, “I was thinking: I’ve failed him.”

Each morning, he checks that his father has taken his medication, then goes to care for the growing list of people for whom he is responsible.