The skies over Toronto’s Rogers Stadium on a late-August night exploded ahead of “Take You Down,” the bedroom banger from 36-year-old R&B superstar Chris Brown’s 2007 sophomore album, Exclusive, soaking every standing surface. When he belted, “Oh, girl, I love the way you sound when you rain on me,” during the apocalyptically horny “2012,” the mic was dripping. But a downpour didn’t stop the singer from ascending into the air in a harness and moonwalking during “Look at Me Now.” Breezy Bowl XX, the tour marking 20 years since Brown’s debut, makes an unsubtle case for the singer as a pivotal force in R&B, hip-hop, and pop by barreling through dozens of disparate highlights. It answers the hypothetical What if Chris Brown headlined the Super Bowl, mesh football jerseys and all? It thrives on extracting an awestruck How did he do that?!

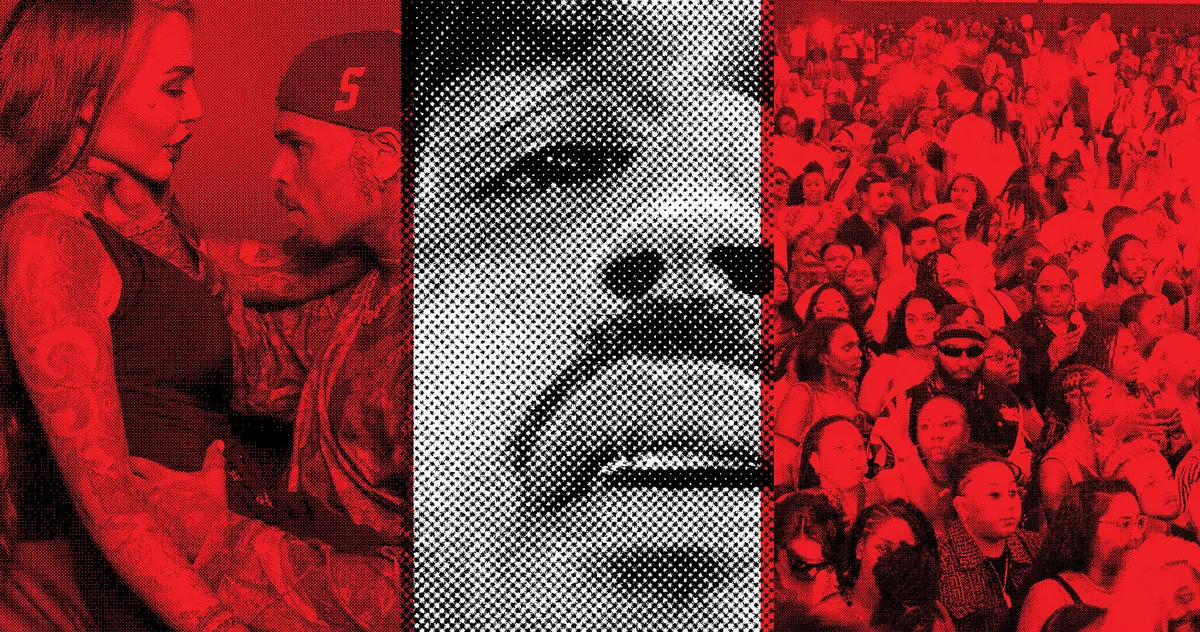

With a Spotify monthly listener count nearing 60 million — in the same ballpark as Beyoncé and Lana Del Rey — Brown feels as inescapable an artist as he ever was. But his grizzled, perseverant energy onstage hardens online, where the singer has stressed that he’s a media outcast. “I BEEN OVERLY BUSTing MY ASS FOR THE LAST 20 years and I understand I will never be recognized for nothing more than drama,” he posted on Instagram in June in response to some discourse over which artists belong in the canon of all-time R&B greats. He’d like us to know that the tour and the cultural phenomena in its wake — the intimate couples’ poses in his meet-and-greet photos, the sold-out shows — are an organic in-fandom achievement, a testament to the us-against-the-world bond the artist shares with his tireless Team Breezy community. It wasn’t always a certainty that the tour, which started in June and ends this month, would go on as planned. The European leg this summer was bookended by developments in a case relating to a 2023 London club fracas in which Brown allegedly assaulted a music producer. In May, the singer was arrested in Manchester and charged with grievous bodily harm with intent and spent nearly a week in custody. He now faces a possible sentence of more than 16 years on multiple criminal charges in the U.K.; the trial is scheduled for next year. He has pleaded “not guilty” to all charges. If he gets put away, at least everyone on the planet got to see him at his gleaming best.

Brown’s own account of his reign states that he has been denied true and lasting redemption for mistakes made at his worst. He shouldn’t be compared to other artists, he argued in June, since singers in his league aren’t forced to “do all this shit by themselves with no help and the media constantly fucking with them.” There are certainly people who will never forgive Brown for beating his ex-girlfriend Rihanna in 2009, or for allegedly abusing his ex Karrueche Tran, after which she received a restraining order against him in 2017. Brown and his fans argue the press and society should give greater consideration to what he’s been through: He witnessed domestic violence against his mother as a child and was diagnosed with PTSD in 2014. He caters to people who see the good in him. “It’s not that I have a careless outlook,” he told Shannon Sharpe in 2023. “I don’t care to make you believe that I’m a great person.” Team Breezy catches him when he falls; he’s a shepherd of the flock. Fuck with one of his fans on social media and you run the risk of Brown making an appearance in your mentions.

He is a symbolic figure, a saint and benefactor of the canceled. People who’ve come to a certain peace with the most appalling incidents in his backstory see someone who’s turning his life around yet unable to escape the insinuation that he’s a psychological tinderbox. Here is a young Black small-town southern man beset by accusations that he is dangerous and still paying for ancient sins committed before he could legally drink. Here is someone who has had industry powers conspiring against him.

But it’s difficult to square his past decade of contemporary hip-hop-radio omnipresence with the idea that Brown is radioactive. Breezy Bowl’s 50-plus-song set list doesn’t cover even half of his still-growing collection of Billboard “Hot 100” entries. Rhythmic-format airplay is the draw for anyone weathering flak for collaborating with him. Drake, whose entourage was involved in a brawl with Brown’s in a nightclub in 2012, circled back by decade’s end to team with him on the diamond-certified “No Guidance.” Chloe Bailey caught hell for working with Brown on 2023’s “How Does It Feel,” then logged her debut album’s only “Hot R&B Songs” chart entry with it. Nickelodeon and Broadway star Leon Thomas’s “Mutt” was sliding off the “Hot 100” this year when a pleading guest appearance from Brown sent it skyrocketing into the top 20, a first for Thomas. Brown is someone you check in with to give a single wings in traditional R&B and trap markets.

He has had this Midas touch since we met him. The allure for Breezy Bowl is the notion that Brown is in the R&B-soul-funk-pop line of succession of Usher, the Jacksons, and James Brown. He emerged from Virginia in 2005, when hip-hop ruled pop culture, with “Run It!,” a song hard enough for clubs but sweet enough for Nickelodeon and thus a rare “Hot 100”–topping debut single. The “millennial Michael Jackson” idea was floated very early on. Brown’s video for 2007’s “Wall to Wall” attempts to be a “Thriller” for a decade of bloody Blade sequels and vampire romance novels. His sliding adaptability in crunk, EDM, hyphy, and trap eras suggests a rare gift. But everyone got more Mike than they planned for. The talent would never come into question, but the nobility of the vessel was often under review. Domestic violence quashed a squeaky-clean image that had once been suitable for Doublemint-gum ads, necessitating a new musical calculus that took a few spins to nail. The motivational platitudes that followed 2007’s Exclusive — “Turn Up the Music,” “Beautiful People” — could be as hokey as they were hooky. But the brash Swizz Beatz team-up “I Can Transform Ya,” Brown’s first single after his 2009 probation sentencing, pointed to hip-hop as the core of his evolution. Rap collaborations ramped up. In late 2010, the smoldering “Deuces” sprouted an EP of remixes featuring Drake, Kanye West, Rick Ross, T.I., André 3000, and Fabolous.

With a fistful of A-list co-signs, Brown leaned into a bad-boy image that dovetailed with the lucrative fusion of soft hooks and tough talk by contemporaries like Drake. Collaborations with L.A. party rapper Tyga, like 2013’s “Loyal” and 2015’s “Ayo,” trace a tone shift as the singer-rhymer began to self-identify as wealthy and obnoxious. You should pay attention, the former single suggested, “when a rich nigga wants you.” Breezy Bowl takes a sweeping crack at reconciling all these movements and acknowledging the precarious 2009–10 bounce back. A video montage after he performs “Transform” shows clips of a teenage Brown’s triumphs, then pivots to recollections of his nearly career-ending shame. “I remember just being in my house, months at a time, trying to figure out what I was gonna do with my life,” he says in voice-over. Solitude offered time for self-improvement and refinement of craft, which the set list reinforces as it twists through a streak of sullen and reflective songs — “Deuces,” 2012’s “Don’t Judge Me.” Then Brown does lap dances for women pulled from the audience during “Take You Down,” sometimes kissing them. The concert’s last hour runs through minor chart hits. Aging but still inescapable Drake and Young Thug duets highlight Brown’s present station: He’s a hip-hop-radio elder who doesn’t always strike gold or platinum but stays chart solvent. He can play the angelic contemporary R&B counterpoint in H.E.R. songs as well as a catcalling big spender for rappers like Gunna. He can dabble in Afrobeats with Nigerian singer Wizkid, and this year’s rising “It Depends” with Breezy Bowl opener Bryson Tiller approximates drill-rap production. He’s a wellspring of hooks when he’s not getting in his own way (and even when he is).

Can someone in demand really be that widely reviled? That outlook feels askew and antiquated. Brown’s reviewers were never uniformly negative — “While listeners can’t help but be reminded of his fall from grace,” Billboard noted in 2009, “Brown also shows us on Graffiti that he’s still a formidable talent”— and the criticism has only softened. But 2023’s double album 11:11 appearing on “Best of the Year” lists and earning the Grammy for Best R&B Album — his first win since 2012’s Fortune — didn’t pierce the Everybody Hates Chris routine. (Did the Grammys hate Chris, or was competition just astronomical with tighter Frank Ocean and Beyoncé works vying for the same genre wins throughout the mid-’10s?) Now, the war over how Brown is perceived has long since ended, no matter how much he plays the pariah. His voice spirits a lot of people away to happier, less haunted times. And the glimmer of lost innocence in his tone has proved much more magnetic than anything he has done to throw the audience off. Very little writing about Breezy Bowl has framed it as a response to a moment when jail time could be in the cards. The narrative of Brown’s summer was that of a generational talent abiding, not a villain prevailing.