By Julie Beck

Copyright theatlantic

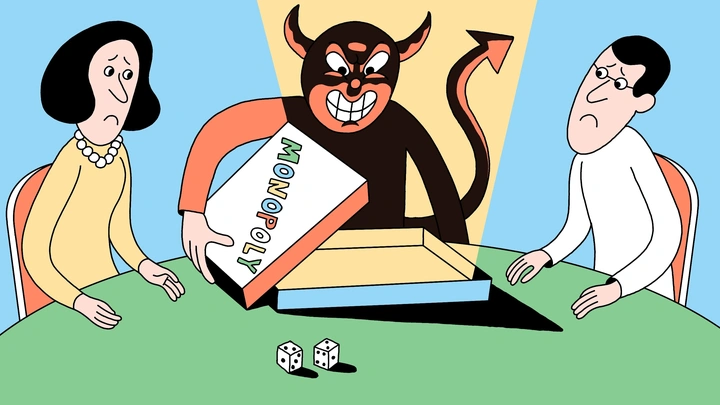

The one rule of Werewolf is: Don’t let them know you’re a werewolf.

Okay, there are a few more rules to the card game than that. You and your friends sit in a circle and are distributed cards, face down, that assign you to the role of villager or werewolf. No one knows who is who. If you are on the villagers’ team, you work with the other villagers to figure out who the werewolves are and kill them, by majority vote. If you are a werewolf, you want to hide that identity and cast suspicion on other people so that everyone will vote to kill a villager instead.

I used to play a lot of Werewolf, back when I had roommates, and I flatter myself that I got pretty good at navigating the many layers of deception and manipulation involved. The werewolves lie, but villagers also sometimes lie—to try to catch someone else in a lie. People change their stories halfway through the game. They accuse and cast aspersions; they sow chaos; they plant seeds of doubt. The game often devolves into shouting.

Some of my friends hate this game—the lying stresses them out, or they don’t like conflict. But what can I say? I love to betray my friends.

Within the confines of the rules, there’s not much I won’t stoop to, and not only in games where lying is the point, as it is in Werewolf. If we are playing Settlers of Catan, where players trade resources and build settlements, I will manipulate you to try to get the best possible deal, and I will downplay how well I’m doing so I seem unthreatening until I swoop in and win in one massive turn. If we’re playing some kind of war game, say, Risk or Root, I will lock in on the person most likely to keep me from winning and work to convince everyone they’re a bigger threat than I am. I don’t always lie—that would be too predictable. A mix of heartfelt honesty and bald-faced lies keeps my opponents on their toes. All for the glory of winning at moving little plastic pieces around a cardboard surface. (If you’re reading this and we play games together: I’m just kidding! I didn’t mean any of that and you can totally trust me.)

I was raised by a father who loves board games—the thicker the rulebook and the tinier the pieces, the better—and who honed my ruthlessness at the dining-room table of my childhood home. But is my merciless game persona merely nurture, or does nature have something to do with it too? Why does the opening of a cardboard box give me tacit permission to act like a sociopath? Does this version of myself actually reveal some dark truth about me that is hidden during my non-game life?

I put that last question to Shane Tilton, a professor at Ohio Northern University who has researched gaming, and he reassured me: “It’s not, You specifically are sociopathic, but there are elements of sociopathic behavior that, for lack of a better term, appeal to the brain.” Tilton compared the pleasure of lying during a game to the vicarious thrill you can get from watching fictional characters do unethical things, except you get to playact that role yourself. One study, published in 2013, found that people can experience a “cheater’s high” from getting away with deception. In the study, researchers gave participants tasks such as unscrambling as many words as possible in a few minutes and answering timed math questions. Without telling participants that the study was about unethical behavior, they designed the activities so there was a way to cheat, if anyone was so motivated. And those who did were pretty pleased with themselves.

For the most part, lying and cheating do seem to be bad for you. Studies have found that lying is associated with negative feelings, low self-esteem, and a reduced ability to make social connections. But part of the reason cheating felt so good to the word-game-study participants could be that it was a low-stakes situation. The subjects got the thrill of doing something bad, minus the usual threat of social stigma or other negative consequences, because hey, it was just a silly word scramble for some researchers they’re never going to see again. Board games are similarly low-stakes. Whether I’m lying about being the werewolf or aggressively invading Australia in a game of Risk after promising my friend I’d leave their troops alone, I get a real high, without real repercussions. “As some Swedes say, ‘All is fair in love and games,’” Tobias Otterbring, a professor who has studied board games at Norway’s University of Agder, told me in an email.

An aspect of real life does hover just beyond the veil of pretend when playing board games, though. After all, you’re usually playing with people you know. “Relationships in the real world can carry over into games,” Ming Ming Chiu, a professor at the Education University of Hong Kong who has studied gaming, told me in an email. This can be to your advantage—or not. For instance, I know my high-school best friends will usually be down to team up with me, and my dad will always, always betray me. (The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.)

And a degree of your real personality carries over too. Some people don’t enjoy acting sociopathic, under any circumstance. A friend of mine, for instance, once got so overwhelmed by all the lies and back-and-forth during Werewolf that midway through the game, she slumped over and admitted, “I’m the werewolf.” What does it say about me that I take such a thrill from the same behavior that stresses out my friend? It seems like it must say something: Tilton told me that even though you’re often playing a role when you’re playing a game, “you’re still yourself.”

Some of Otterbring’s research has shown that people who frequently play board games tend to have personalities that are higher in openness to experience. That doesn’t sound so bad. But a study from the 1980s found that people were better at bluffing games if they were high in Machiavellianism—a personality trait of ruthless manipulation. That seems less good.

The experts I spoke with advised me not to worry. Nailing down the personalities of people who like or are good at games is difficult, because the many different kinds of games that exist appeal to many different types of people. Rachel Kowert, a psychologist who studies gaming, offered an encouraging assessment of what my game personality says about me: “What I’m learning,” she said, “is that you like to be playful, and are probably competitive, and you have cool friends who also like to play games with you.”

She pointed me toward the website of Quantic Foundry, a market-research company that studies gaming. I took their “board games motivation” quiz, and I’ll be darned if Kowert wasn’t pretty much spot-on. I scored very high on the “need to win” and “social manipulation” metrics, but I also scored high on the “social fun” metric. I do enjoy cooperative games where all the players work together, as well as party games such as Telestrations, where the only goal is to have a laugh. I’m really not always out for blood. And as intense as I can be while playing, I don’t carry that with me after we shut the box.

Of course, how you behave in a game can still affect how people see you outside of it. If you’re a poor sport, or if you go too far with the playful deceptions and actually start bending the rules, that could degrade your real-life relationships. But people can usually tell what’s all in good fun. Even if you’re backstabbing, deceiving, and betraying one another, “our brains are very smart,” Kowert said. “We know what’s real and what’s not.” For instance, in a game, “I’ll throw my husband under the bus so quick,” she said. “And I wouldn’t do that in real life.”

Both Tilton and Kowert emphasized that the main thing games teach their players is social skills. Tilton has used Werewolf in the classroom to teach small-group communication. Because the fantasy scenarios of games don’t really translate to real life, what’s most likely to carry over is the practice you get at reading people and communicating with them.

For example, if I were to offer aspiring Werewolf champions one piece of advice: When caught in a lie, do not admit to it. Rather, you must double down and commit to your lie even harder, so that the other players are forced to choose sides between you and your accuser. This is not how I would conduct myself in my normal life, where I am a nice and honest person (I swear!) who is rarely accused of much worse than leaving my dishes in the sink. But perhaps my utterly depraved Werewolf behavior has helped me practice the more broadly applicable skills of standing up for myself, being persuasive, and making my opinions heard. Perhaps being a board-game sociopath is helping me be a more effective member of society.

Or maybe that’s just what I want you to think.