‘The Smashing Machine’ Is a Triumph For Dwayne Johnson—and for the Seminal MMA Documentary That Inspired Benny Safdie’s Film

By Vince Mancini

Copyright gq

This story contains spoilers for true events depicted in The Smashing Machine.

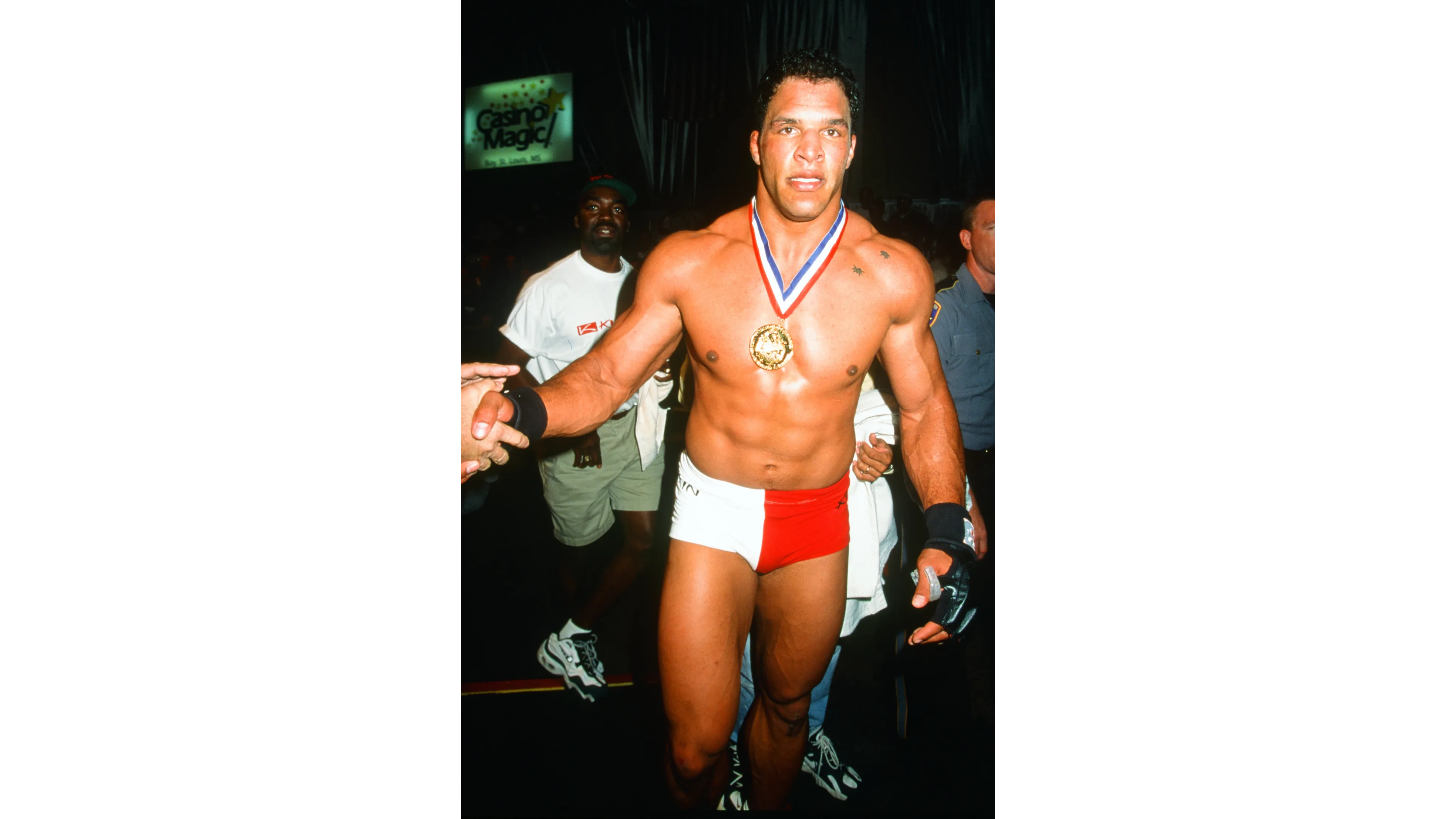

It looked like a classic Hollywood ending: Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, sobbing (“uncontrollably,” per Variety) through a 15-minute standing ovation after the Venice Film Festival premiere of Benny Safdie’s The Smashing Machine, in which Johnson plays MMA fighter Mark Kerr. With a surprisingly vulnerable, locked-in performance in one perfect role, Johnson had the industry rags asking “Is Dwayne Johnson headed to the Oscars?”

If he is, that’s great for Johnson, who’s finally nailed the serious-actor transition that so many believed him capable of for so many years. But the early acclaim for Safdie’s The Smashing Machine also completes an even-longer redemption arc—for the real Mark Kerr, and for the original The Smashing Machine, a seminal documentary about Kerr’s journey through the wild early days of MMA, directed by John Hyams and released in 2002.

That big guy standing next to The Rock on so many red carpets, the one with the squinty smile and smashed-up ear, maybe missing a few front teeth? That’s Mark Kerr. He might not be the most recognizable face to the festival paparazzi, but as it turns out, his story has inspired even more movies than the one in which The Rock plays him. The first one was Hyams’s film.

While you can’t currently find it on any streaming service, The Smashing Machine (full title: The Smashing Machine: The Life and Times of Extreme Fighter Mark Kerr), an indelible profile of Kerr circa 2000–2002, lives rent-free in the heads of most MMA fans of a certain age—and a surprising number of Hollywood directors too. Safdie is clearly one of them; the Dwayne Johnson/A24 Smashing Machine is not only based on the documentary, but at times feels like a meticulous, shot-for-shot re-creation of it.

There’s a scene that frames the trailer—an older woman asking Johnson-as-Kerr in a doctor’s office waiting room, “Do you hate each other when you fight?”

“Absolutely not,” Johnson replies, channeling Kerr’s nasal-voweled Toledo, Ohio, accent and reassuringly shaking his head. It’s one of many scenes pulled essentially word-for-word from an unscripted moment in the doc.

“If you look at the trailer, it’s uncanny what faithful re-creations they did,” John Hyams says. “Not just of the scene in the office—there are loads of what look like the original shots.”

Hyams, now a prolific film and television director perhaps best known for rebooting the Universal Soldier franchise in 2009, has a consulting-producer credit on Safdie’s film. While he wasn’t involved in the project creatively, he seems thrilled at the prospect of seeing an up-and-coming auteur’s take on his 23-year-old documentary.

“In some ways,” Hyams says, “I think maybe they’re gonna make the most truthful biopic that’s ever been made. Even down to Kerr wearing the exact same hat in some scenes—him running up the stairs in Newport Beach, him making a smoothie at his house. If nothing else, they seemed meticulous in their attempt to re-create these things accurately.”

The fact that Johnson and Safdie chose to re-stage so many moments from the nonfiction Smashing Machine speaks volumes about what Hyams’s film achieved. The Smashing Machine: The Life and Times of Extreme Fighter Mark Kerr is the kind of generational doc that not only offers a portrait of its subject as compelling as any novel, but also captures a subculture on the brink of massive change. The version of the UFC seen in Hyams’s movie is gone forever—and in many ways, the doc itself is the best evidence that it ever existed.

The doc that would belatedly make Kerr famous started, and could only really have existed, because Hyams, an aspiring filmmaker at Syracuse (as well as the son of a director), was friends with Jon Greenhalgh, who had been on the Syracuse wrestling team with Kerr. In those days, Hyams and Greenhalgh and their friends would gather to watch early UFC events to see their mutual friend, Kerr, who somewhat to their surprise, ended up winning—at UFC 14 and 15, in 1997.

“I had no interest in documentary at the time, but Jon had this friendship with Mark,” Hyams says. “We would watch these fights and it was just super wild to see this guy who I had met a couple times in college who was winning. And then at one point, Jon called me and said, ‘Hey, what do you think about if we follow this guy for a documentary about a fighter?'”

They scrounged together $10,000, some of it from local bar patrons, and set off for what they imagined would be four to six months of filming.

“At the time, my closest reference to anything like that was Pumping Iron,” Hyams says, referencing the classic 1977 documentary that introduced Arnold Schwarzenegger and Lou Ferrigno to the entertainment world. “I thought, okay, we could maybe do the Pumping Iron of this sport. Because, in a similar vein, it was this kind of niche subculture that most people had a preconceived idea about.”

Those preconceived ideas were largely a result of the UFC’s own early marketing, which sold it as an extreme, no-holds-barred blood sport starting from their first event, in 1993. Politicians pushed to get it banned—notably John McCain, who called it “human cockfighting” and sent letters to the governors of all 50 states asking them to ban the sport.

By the time Kerr won the heavyweight division at UFC 14, the UFC was slogging its way through a string of events held in the deep South (most often Birmingham, Alabama, and Augusta, Georgia) with live attendance below 5,000 spectators. It was a situation that would persist basically until UFC 28. That was the first event after the company was bought by Zuffa, the company founded by Station Casinos heirs the Fertitta Brothers, who had hired their friend Dana White as the company’s president, and tried to take the company (more) legit. With Zuffa on the brink of bankruptcy, Donald Trump threw them a lifeline, allowing them to stage the event at his Atlantic City Casino. UFC 28 became the first UFC sanctioned by an athletic commission. And so began the Donald Trump/Dana White bromance that we all know and despise, which persists to this day.

Although fans recall the pseudo-legal period prior to the so-called “Zuffa era” fondly, the UFC was in such turmoil that Kerr himself left the UFC for greener pastures and bigger paychecks fighting for PRIDE, another MMA promotion, in Japan. This was the moment when Hyams’s cameras started rolling.

“Our initial plan was we would shoot Pride 7 [in 1999],” Hyams says. “So we’d start with an event and you’d kind of see the inner workings and the locker room and everything, and it’d just be kind of fly-on-the-wall storytelling. We’d film the fight, we’d go home with him and film his recovery from the fight, and then we would cover the training for the next one. And then we would end it with Pride 8, I don’t know, four months later or whatever it was. That was the plan, anyway.”

At the time, Kerr was undefeated and one of the top guys in the sport. That in turn allowed Kerr a certain amount of pull with PRIDE, an organization widely reported to have heavy ties with the Yakuza. Hyams credits his close working partnership with Kerr as the only reason they were allowed to shoot in the first place.

“Every time there was an event, they would cancel our permission to shoot the day before the fight,” Hyams says. “And then we would get Mark to threaten to pull out of the fight, and then they would let us back in and renegotiate. Several of those guys that we sat down with are not alive anymore, under mysterious circumstances. I think one guy was found hanging in a closet or something. It was a whole shady world. And if we had been doing something about, say, Gary Goodridge we probably wouldn’t have gotten any access. Mark facilitated all of that.”

Kerr turned out to be a perfect subject, for reasons that went far beyond just serendipity and access. He had the ability—rare for athletes in general and for fighters in particular—to articulate exactly why a seemingly normal, salt-of-the-earth Ohio guy would choose to participate in this brutal and depraved sport. He struck Hyams as someone who happened to be very good at a thing he didn’t necessarily enjoy doing.

“I don’t think it’s in Mark’s nature to want to pound the shit out of another person,” Hyams says. “But he was good at it. And I think that started to wear on him, psychologically.”

Yet Kerr would get a faraway look in his eyes when he opened up about how it feels to be fighting in your underwear in front of thousands of screaming fans. In the film, he describes it as a high unlike any other, an almost childlike reverie passing through a battle-scarred face.

PRIDE 7 didn’t turn out the way Hyams and Greenhalgh imagined, but it was a curse that became a blessing. Kerr fought a Ukrainian kickboxer named Igor Vovchanchyn, who rocked Kerr with a punch in the opening minutes of the fight, before Kerr applied his champion wrestling pedigree and size advantage to take Vovchanchyn down. Kerr held him there for much of the first round, not doing much damage, but applying control and avoiding most of Vovchanchyn’s counters. At the start of the second round, a visibly gassed Kerr attempted another takedown, and the two fighters ended up in a scramble. Vovchanchyn kneed Kerr in the head while Kerr was still on his hands and knees, and the ref stopped the fight. It was initially ruled a knockout, but the result was later changed to a no contest. “Knees to a grounded opponent” are still outlawed in the UFC, and were supposed to have been illegal at PRIDE 7, but PRIDE’s rules changed from event to event, creating enough confusion that even the bout’s referee apparently didn’t know fouls he was meant to be calling.

That sense—of MMA being a semi-lawless, multinational world in flux—pervades Hyams’s film. It’s part of the reason MMA fans love the movie so much. Kerr himself came out of a singular era. Royce Gracie, a 6’1″, 180-bound beanpole who was chosen as the Gracie family’s representative specifically for his relatively unimposing appearance, proved the utility of submission grappling against much bigger opponents in the first few UFC events. Then guys like Mark Kerr and Mark Coleman (a key supporting character in the Safdie version, played by former Bellator light-heavyweight champion Ryan “Darth” Bader) proved that a great wrestler who’d learn some submissions, and especially submission defense, as well as maintaining a size advantage, was a fearful combination. They got on the gear and bulked up—Kerr went from wrestling at 190 to being as big as 280 at his peak. And then, as it continued its quest for legitimacy, the sport in some ways pulled the rug out from under guys like Mark Kerr, instituting more weight classes, rules against headbutting, and stricter doping protocols that favored quicker athletes.

“[That era of MMA] was kind of like nineties basketball,” Hyams says. “Nineties basketball in some ways was more entertaining because everyone was more specialized. There weren’t seven-footers shooting three-pointers. You had a guy who could shoot a midrange jump shot, and then you had your three-point specialists. Everyone had more specialized skills, and there was a lot more variety to it, so it was super entertaining to the fan.”

A lot of this is context and backstory to the Kerr drama detailed in Hyams’s Smashing Machine—but you also get the sense from Hyams’s film that MMA as a sport is starting to move away from Kerr just as he’s hit his peak, with the turmoil in his personal life mirroring that sense of paradigms shifting. What happens to Kerr after the Vovchanchyn fight ends up being more important than the fight itself; and was no less a turning point for Hyams and his production team.

“It seemed like there was a big emotional release after that fight that even seemed beyond just the losing of a fight,” Hyams says. “This was our first week or so with the guy, and I think we kind of noticed that things were a little off and a little strange in general. I didn’t know the guy well, so I’m like, ‘Maybe this is just how he always is.’ But after that fight, it was clear he was going through something. His girlfriend, Dawn, at the time was present and there was a dynamic going on there. So when that whole thing ended, and then we went back to Phoenix with him, that was when we realized that our movie was maybe going to be about some other things other than just fighting.”

It turns out Kerr had been struggling with opiate addiction, presumably partly as a result of competing in a sport that destroys your body and requires frequent pain management. He was also in a codependent relationship with a fellow addict (Dawn, played in A24’s version by Emily Blunt). The scene in the Safdie version where Johnson’s Kerr asks a Japanese doctor if he has “anything stronger” and then laughs when the doctor suggests Advil is another bit taken straight from the documentary. In Hyams’s film, we also see Kerr nodding out, and ultimately ending up in the emergency room after an overdose.

Great documentaries always offer more than they promise, and that can be something of a devil’s bargain for the filmmaker. Hyams now had a story that was arguably bigger than just Pumping Iron, but he was also in a de facto business partnership with a drug addict embroiled in a tangle of blurry, personal/professional relationships and complex finances, who was also famous for his ass kicking. Nonetheless, there was nothing to do but keep filming.

Hyams’s camera follows Kerr as he drops out of a few Pride events, goes to an in-patient rehab, and breaks up with Dawn. We watch him dispose of an objectively insane quantity of medicinal vials, presumably steroids and opiates. Eventually, in an attempt to get his life and career back on track, he relocates from Phoenix to SoCal to train with Bas Rutten, a Dutch kickboxer/former Amsterdam bouncer and gregarious goofball well-known to many MMA fans as arguably the most entertaining personality the sport has ever produced. (Rutten, who plays himself in Safdie’s film, is one of many future MMA stars who make cameos in Hyams’s film; you can also see Kerr throwing around future UFC heavyweight champion Ricco Rodriguez in Rutten’s training room. Rodriguez would himself go on to appear in Celebrity Rehab with Dr. Drew in 2009).

In the final chapter of Hyams’s film, Kerr ends up back in PRIDE, fighting in a Grand Prix tournament that, if he wins his preliminary bout, will put him in line to fight Coleman, his close friend, fellow wrestler, and mentor. The doc feels like it’s all building towards a climactic fight between sensei and protegé that neither really wants, but that both feel compelled to accept for the money, their families, and careers. Except the documentary proves that real life can’t be compelled by narrative conventions: Kerr ends up losing a close decision to Kazuyuki “Ironhead” Fujita, and the Kerr-Coleman bout never materializes.

“Twenty years ago, people always said, ‘Well, you can’t end it that way,’” Hyams says. “In the end, it’s like, Kerr and Coleman have to fight.”

Hyams took his own crack at a scripted version of Kerr’s story before the documentary was even released. They’d shot the doc—they intended to call it The Specimen, which had been an early nickname of Kerr’s—and then run out of money. Hyams and his filmmaking team (which included Greenhalgh, producer-cinematographer Steve Schlueter, and producer-sound guy Neil Fazzari) were trying to drum up some more funds to finish the edit. A mutual friend put Hyams and Greenhalgh in touch with Peter Berg, who connected them to Berg’s agent, the super-agent Ari Emanuel. Emanuel couldn’t act as the sales agent for The Specimen because of a prior agreement, but he suggested Hyams write a scripted version as a vehicle for his client Mark Wahlberg. Wahlberg, who famously fictionalized Emanuel as Ari Gold in Entourage, ultimately passed, and Hyams and co-sold the project to a different producer.

Eventually, producers Gavin and Gregory O’Connor came on board to raise the finishing funds for The Specimen, which would become known as The Smashing Machine only after its Tribeca premiere. The title change was one of the purchase conditions from HBO, who thought The Specimen sounded too medical. (“They sent us a list of titles,” Hyams says. “One of which, I remember, was The Bloody Punch.”)

In 2007, the O’Connors returned to inquire about turning The Smashing Machine into a scripted feature, with New Line interested and Gavin O’Connor attached to direct. Unfortunately for Hyams, the producer they’d sold the rights to after Wahlberg passed wasn’t interested in giving them up. And so Gavin O’Connor went off to direct Warrior (2011), starring Tom Hardy and Joel Edgerton as two estranged brothers (rather than friends) who meet in the finals of an MMA tournament. Was the world getting Warrior a good trade for the John Hyams–scripted Mark Kerr movie we never saw? Impossible to say.

“One really interesting story that we had in the script was Kerr’s first fight in Brazil, where he fought in the Vale Tudo tournament. It was going to be three fights-in-a-day type of thing. And he had never been in a professional fight in his life,” Hyams says.

“He kind of tells this story in our movie, how he’s in the bathroom before the fight puking his brains out. He’s totally freaked out. And then he goes out there and he beats the shit out of Paul Varelans. And then the second guy, Mestre Hulk, [Kerr] beats the shit out of him.” Kerr’s last fight that day was against Fabio Gurgel, a jiujitsu champion known to later generations as the trainer of BJJ legends Demian Maia and Marcelo Garcia.

“It’s the most brutal fight you’ve ever seen,” Hyams says, “because it’s basically a guy who’s really proud and won’t quit and is just getting the shit pounded out of him for a half hour straight. Mark is headbutting him, he’s punching his face so many times that he’s broken his hand and his hand is bleeding, and ultimately he developed some crazy staph infection from it. And he’s just trying to end this fight, but [Gurgel], his face is just like pulp, and they just let it go the distance because the guy was really proud. The next day, Mark’s won the tournament, his hand is all fucked up and in some kind of cast, and he gets a call from Fabio Gurgel’s people. He says wants Mark to come over for tea.

“So Mark went to Fabio Gurgel’s house and they all sat, with family and cousins and everyone, and Fabio, whose face is a fucking basketball with like a neck brace or whatever, they don’t speak any English, but Mark sat there with them and had tea. I think in our script we re-created the tea party a little bit,” Hyams says.

It sounds like it would’ve been a great scene. Yet the DNA of the original The Smashing Machine is also unmistakable, I would argue, in another successful fight film from the late aughts: Darren Aronofsky’s The Wrestler, from 2008, with Mickey Rourke as a fictional, washed up pro wrestler, Randy “The Ram” Robinson. So much of The Wrestler—from the way cinematographer Maryse Alberti’s handheld camera perches just behind Rourke’s broad shoulders (a far cry, stylistically, from any of Aronofsky’s meticulously blocked earlier films) to the locker-room scenes to the moment when The Ram disposes of his steroid vials—mirror visual and narrative beats from The Smashing Machine.

Rourke’s whole vibe in the film, that of a lovable galoot with a slightly chaotic personal life, seems to match Kerr in the doc to a T. The 1999 wrestling doc Beyond the Mat is often cited as an influence on The Wrestler, though Hyams thinks he remembers either Aronofsky or Rourke mentioning The Smashing Machine in one interview or another. That may be apocryphal, but all I know is that when I started watching The Wrestler a few nights removed from a viewing of Hyams’s The Smashing Machine, my wife, who hadn’t seen either movie until that week, asked, unprompted, “Is this that same movie from the other night?” (To further these eerie parallels, it was announced back in January that Aronofsky has plans to direct Dwayne Johnson in another A24 feature, entitled Breakthrough.)

For his part, Hyams says he isn’t miffed by any of the later developments with The Smashing Machine, even though he isn’t directly profiting from them, having long ago sold off his rights. “About a year ago when [the scripted The Smashing Machine scripted version project] started to sound like, hey, this is kind of a real thing and Benny Safdie is going to make it,’ Hyams says. “When I heard that, I thought, ‘Oh, they’re going to actually make a good movie out of it.’”

“I thought, well, if Mark could cash in on any level with this and maybe just have people talk about and remember what he was in his career, that would be great,” Hyams says. “This guy totally opened himself up to us in a very extreme way, and in a way that was, could’ve been, quite frankly, potentially very threatening to his livelihood.”

Early on, Hyams had made a deal with Kerr that if Kerr opened himself up completely and let them shoot everything, then they would allow Kerr “complete veto power” over the movie. “We had an agreement,” Hyams says, “where we told him, ‘If there’s anything in there that you don’t want in there, then it’ll be out.’”

The edit itself took two years. Throughout the process, Kerr and a succession of new managers pleaded with Hyams and Greenhalgh to show them the footage—which wasn’t an outlandish request for a movie that could, in fact, affect Kerr’s career. But Hyams was reluctant to show them anything before they’d gotten the cut just right, knowing that he’d only really get one shot for Kerr to see it in its proper context.

“We kind of had to weather those storms, and we finally finished the thing and rented out a screening room in New York,” Hyams says. We had a screening with just Jon and myself, and Mark sitting like a row in front of us in there and we played it for him. That was a pretty intense experience, for someone to relive this wild year of his life a couple years later. And he was like these big shoulders right in front of us, you could see his body just breathing and then heaving and sobbing. The movie ended, and the lights went up, and he gave us this big hug and cried. And he said, ‘I love it.’ He didn’t veto anything. We didn’t change anything after that.”

The MMA world depicted in The Smashing Machine, of a niche industry fighting for relevance, with fighters trying to show that they were real athletes, and thoughtful humans to boot, is a far cry from the UFC of today, which has become so mainstream and so tied up in right-wing politics that President Trump has repeatedly stated he plans to hold an event on the White House lawn. In 2016, Zuffa sold the UFC to WME-IMG and its co-CEO Ari Emanuel for $4 billion. Dwayne Johnson, meanwhile, has close and long-standing business ties to Emanuel, and has been represented by WME since 2011.

It’s a far cry from the state of affairs when The Smashing Machine’s release in 2002. Back then, Hyams says, Zuffa would try to scrub any mention of the movie from MMA message boards: “They were not happy with this portrayal of their sport that they were trying to launch, which I can understand.”

It could be that the UFC has come around to the old adage that any publicity is good publicity. Or to a belated realization that Mark Kerr, a straightforwardly good guy by most accounts, is one of the best ambassadors the sport could’ve asked for. With the benefit of hindsight, The Smashing Machine (2002) is even more of a redemption story for its star and chief facilitator, Mark Kerr.

It’s hard to imagine we’d still be thinking about The Smashing Machine in the same light if Hyams and his collaborators had followed, say, Phil Baroni (currently on trial for allegedly killing his girlfriend in Mexico), or Jon “War Machine” Koppenhaver (serving life in prison for rape and kidnapping) or Conor McGregor (a burgeoning right-wing demagogue found civilly liable for a rape in 2024) or BJ Penn (making headlines for claiming his family has been replaced by “impostors”) or any number of other fighters whose personal lives have gone down much darker paths than Kerr’s. MMA, just like the NFL and professional boxing, has illustrated repeatedly that putting your body through what the sport requires often doesn’t make for an easy ride into the sunset for its past champions and pioneers. Kerr, thanks in part to Safdie and Dwayne Johnson as well as Hyams, offers at least one example in which some kind of happy ending is possible.

“The funny thing is that in the end, from back then till now, there’s been all sorts of issues with all kinds of people who are involved with that documentary and threatened lawsuits of one sort or another,” Hyams says. “The one person who’s never done that is Mark. He’s the one guy who always was just able to stand up. He could always sort of stand by everything he did in there.”

“The movie was about a bunch of human beings who are flawed, like all of us,” Hyams says. “We weren’t even making a comment on the sport. We weren’t saying ‘this is good, this is bad.’ We were just saying, ‘This is the portrait of a fighter.’”