Copyright timesnownews

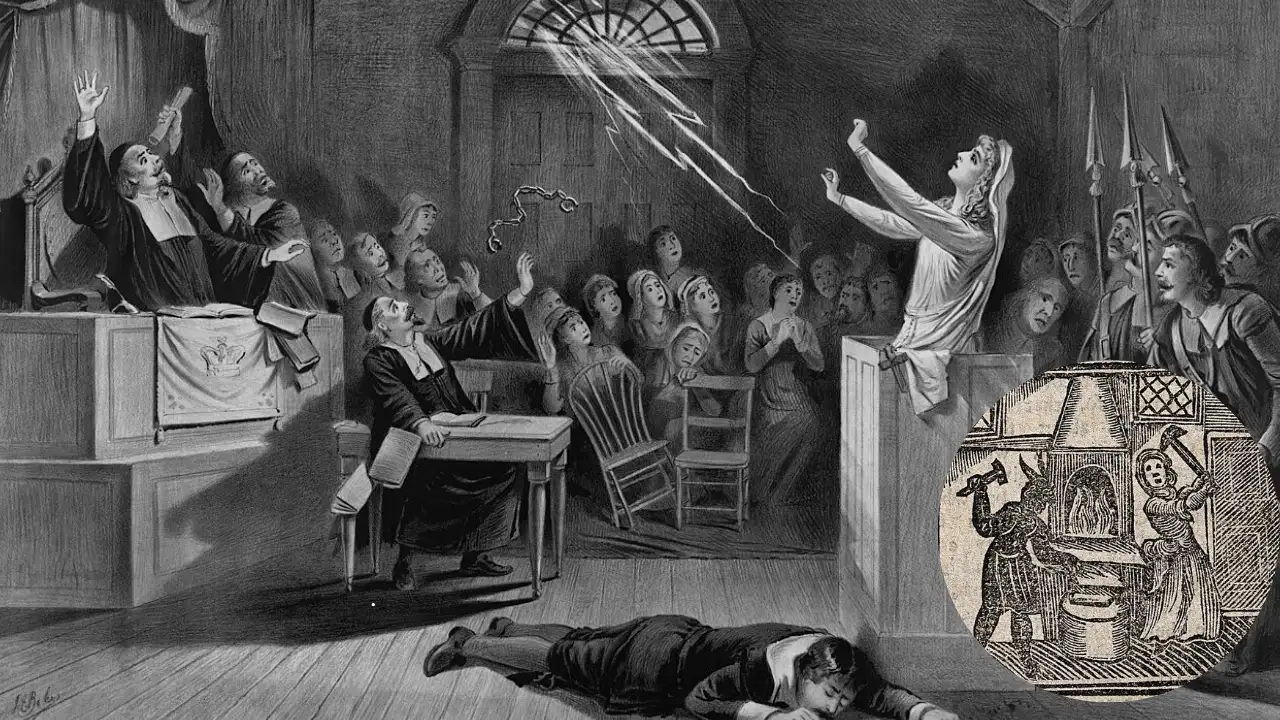

History's one of the notorious events, and a coveted attempt to dismiss the native's rebellions against colonisers. This is the Witch Hunt, of America's indigenous communities, all thanks to the European colonists. This is the infamous Salem Witch Trials in Massachusetts. The Salem Witch Trials ran from 1692 to 1693. This was a moment when hysteria, religious dogma, and colonial anxieties collided with the consequences unthought of. Over 200 people were accused, 30 were convicted, and 19 were executed by hanging. One man, Giles Corey, was in fact, pressed to death under heavy stones, as noted by the New England Law Boston's piece, titled The True Legal Horror Story of the Salem Witch Trials. Yet, the truth is, the trials were hardly about witchcraft. Beneath the surface, lay deeper tensions, and the biggest one was the colonial fear of rebellion, displacement of Native Americans, and silencing of women who refused the Puritan expectations. Why Massachusetts? This is because colonists of Massachusetts Bay were reeling from years of instability, collapse of old charter, and continuous wars with indigenous tribes. Nothing was more convenient than the weapon that is both spiritual and political in nature - Witchcraft accusation, used against the "others", who actually were native to the land. How Witchcraft Was Used To Combat The Colonial Threat Of Native Resistance Before the Witchcraft trials had begun, the colonial Massachusetts was gripped in the fear of Native American uprisings. The Wabanaki Confederacy and other indigenous groups continued to fight the English settlers during King Philip's War from 1675 to 1678 and King William's War from 1689 to 1697. These conflicts had devastated frontier towns and also left deep scars among Puritan communities. The Puritans colonists saw these attacks as the manifestations of the Devil's power, whereas, in reality, these were just attacks from indigenous tribes, trying to safeguard their native land. The Puritans equated the realities with spiritual forces, for instance, famine, disease, or even defeats in wars were believed to be Satan's Work. This is when their defeat in wars and facing uprisings were seen as demonic rebellion by the natives. Colonists even labeled Native spiritual practices as 'Witchcraft'. In fact, something similar had been seen across colonies in other nations too. A 2023 piece published in the AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples notes that rebellious women were labelled as witches, and were removed through motivated with-hunting by the colonisers in India. This framing had served dual purpose. It justified colonial expansion while demonised indigenous resistance. In America, the branding of Native Americans as agents of Satans, Puritans were able to reinforce the idea that their wars were holy crusades, while colonies were under siege by the Devil. The Gendered Nature Of Witch-Hunting Why were women the main targets? It is impossible to unsee the political motive behind witch hunt. Elizabeth Reis, in Dammed Women: Sinners and Witches in Puritan New England notes that 78% of those accused were women, many of whom were unmarried, widowed, and outspoken. Puritans doctrine taught that women were spiritually weaker, which made them more susceptible to the Devil's influence. They were believed to harbour unruly behaviour and dangerous independence. Reis also notes that many women confessed to witchcraft out of fear or guilt, or genuinely believing that they succumbed to evil because society had long taught these women that there actions were sinful. In fact, those who did not conform to society's rule, including healers, midwives, or assertive women, were also labelled as witches. How Did The Salem Witch Trials Begin? The hysteria began in February 1962 in Salem Village, modern day Danvers. This is when Betty Paris, 9 and Abigail Williams, 11, daughter and niece of Revered Samuel Parris, were reported to have suffering from violent fits and hallucinations, as archived by John Hale. The local doctor was unable to find any physical cause, and declared the girls to "bewitched". Soon, other girls, including Ann Putnam Jr. and Elizabeth Hubbard also began to display similar symptoms, including screaming, contorting their bodies, and claiming to see figures tormenting them. Under pressure to identify their tormentors, the girls accused three marginalized women, notes Amy Nicholas, in Salem Witch Trials: Elizabeth Hubbard. These women were Tituba, an enslaved woman of Caribbean with a native descent; Sarah Good, a destitute beggar; and Sarah Osborne, an elderly woman who rarely attended church. Tituba’s coerced confession, in which she spoke of signing the Devil’s book and seeing black dogs and spectral cats, ignited a wildfire of fear. Her testimony confirmed every Puritan nightmare, that Satan was recruiting among them, and that women, servants, and outsiders were his agents. By spring of 1692, hysteria had spread beyond the Salem Village, and over 200 people were accused, and local jails overflowed. Colonial courts were already suspended, and no established legal system was in place. This is when the newly appointed Governor William Phips created a Special Court of Oyer and Terminer on May 27, 1692, to handle the cases. The name meant, "to hear and determined". The surprising thing: the court operated without clear laws, relying heavily on spectral evidence, dreams, visions, and ghostly apparitions. Puritan judges reasoned that if an accuser saw a spectral image of someone tormenting them, the accused’s spirit must be under Satan’s control, and thus guilty. Even respected citizens, including former ministers like Reverend George Burroughs, were accused and condemned. In August 1692, Burroughs recited the Lord’s Prayer flawlessly on the gallows, something witches were believed incapable of, but was executed anyway. A Wave Of Executions Between June and September 1692, 19 people were hanged on Gallows Hills, and one man, Giles Corey was crushed to death for refusing to plead guilty, notes Heather Synder in Giles Corey: Salem Witch Trials. Five more died in jail and dozens were languished in disease-ridden cells for months. Their entire families were torn apart, mothers and daughters were accused, and neighbours too turned into informants to save themselves. By autumn, the madness began to falter. Accusations had spread so widely that even prominent citizens, including the governor’s own wife, were accused. The credibility of the trials crumbled when Increase Mather, president of Harvard College, publicly denounced the use of spectral evidence. In October 1692, he famously declared, “It were better that ten suspected witches should escape than one innocent person be condemned.” His statement struck at the heart of Puritan justice, forcing the colony to confront the moral catastrophe it had unleashed." On October 8, 1692, Governor Phips banned spectral evidence from being admitted in court. Three weeks later, on October 29, he prohibited further arrests, released many accused witches, and dissolved the Court of Oyer and Terminer. By early 1963, the newly formed Superior Court of Judicature retired all the remaining cases, and nearly all cases ended in acquittal. In 1702, the Massachusetts General Court declared the trials “unlawful.” By 1711, the colony passed a bill restoring the rights and good names of 22 victims and granted financial restitution to their families. Even centuries later, the impact are still seen in the people of Massachusetts. For instance, in 1957, the state formally apologized, in 2001, another act cleared five more names from those put in trials. The final exoneration came in 2022, when additional names. The final exoneration came in 2022, when Elizabeth Johnson Jr., the last convicted Salem witch, was officially pardoned, 329 years after being condemned.