The third in a series of five essays entitled the Abyss of Civilization.

There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.”

— Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Philosophy of History (1940)

“The original affluent society was achieved not by the accumulation of goods but by the desiring of little.” — Marshall Sahlins, Stone Age Economics (1972)

Prelude

Civilization is a monster—one of our own making.

We did not set out to create it, yet we remain responsible for what it has become, because we would not—or could not—stop it.

Once whole, the psyche (mind, brain, and body) began to unravel with the rise of civilization, the third stage of human existence. It was here that decadent values—destructive and opposed to well-being—entered our lives and took hold.

We allowed this turn six thousand years ago, and it has only worsened since. The monster that resulted propagates destructive ideas. It is a dynamic entity without conscious intention, living through us—our minds mostly—expanding and thriving at our expense.

The purpose of this essay series, The Abyss of Civilization, is to press this claim: that in naming our singular foe, we may finally direct our energies toward overcoming it.

Scholars generally agree that things changed for the worse once civilization began. In 1963, historian Samuel Noah Kramer called Sumer “the first sick society,” describing the period around 2500–2000 BCE—nearly two millennia after its start. Yet evidence shows the sickness began almost immediately.

One reason we can say this is by comparing the Uruk era in the ancient Near East (ANE) with the 2,700-year Ubaid era that preceded it. In that long span, villages and small towns were organized on an agricultural and broadly egalitarian basis, with little evidence of fortifications or organized warfare. The beginning of civilization, by contrast, is marked by fortified cities, conflict, and inequality.

Another reason, drawn from the first two essays of this series, is that male gender roles quickly fused with violence in the opening centuries of civilization. By 3600 BCE, an all-male priesthood had consolidated and secured control of the major cities on the Sumerian plain. Over the next two centuries, this priesthood designed four “ruptures” (processes that dramatically undermine human well-being) to eradicate any chance of confronting the Frankenstein-like monster of civilization.

Yet even though the evidence is compelling, historians and other scholars fail to recognize the importance of the two centuries after 3600 BCE—the “Great Ruptures Period” (GRP)—or to see how profoundly civilization was strengthened by it. They faithfully document what the archaeological record reveals but stop short of theorizing the scope or effect of these monumental changes as they unfolded. Nor do they trace their aftermath. This new stage of our species’ existence is rarely acknowledged as such, despite its profound differences and its role as the source of all that we think, do, and believe today. I have identified many reasons for this disregard, each crucial to understand, and will return to them in detail in the final essay of this series.

Civilization should be recognized as a distinct stage of human existence; one characterized by long-term decline interrupted by occasional but brief periods of renewal. As we have seen in the first two essays, the initial ruptures—negatively structured gender roles and the annihilation of the Ontological Feminine (O/F)—only intensified as civilization ‘advanced. We also witnessed the cunning and acumen of the Sumerian priesthood, who understood themselves to be launching an attack on Being itself—our essential nature and core characteristics.

The First Two Relational Meaning Systems: Healthy Foundations of Human Meaning

The Missing Typology

How humans relate to their surroundings and draw meaning from them is a fundamental need—though not uniquely human. The best-known Relational Meaning System (RMS) is ‘religion’ but that only applies to civilization. It cannot account for earlier modes of meaning-making, especially those that shaped life before civilization: Stages I and II.

Typology of Relational Meaning Systems

Level No. Epoch Stage Period* Years % of Homo sapiens era A 1 Animism Stage I & II 300,000 – 12,500 BCE 287,500 95.80% B 2 Chthonic Spirituality Stage II (Transition) 12,500 – 4000 BCE 8,500 2.80% C 3 Named Gods Stage III – Civilization 3500 – 2300 BCE 1,300 0.40% 4 Sky Gods Stage III – Civilization 2300 BCE – 1376 CE 3,676 1.30% 5 Monotheism Stage III – Civilization 1150 BCE – 1491 CE 2,650 0.90% 6 Capitalist – Monotheism Stage III – Civilization 1492 CE – Present (~2025) ~500 0.20%

This is not merely a matter of terminology but of how humanity made sense of, and oriented itself within, dramatically different environments and ways of life. That much is well supported by scholarship. Missing is any sustained account of how these systems evolved, interacted, and transformed—and why. I was stunned to find no such typology had ever been attempted, despite the glaring need.

Given our purpose here—to understand why the Sumerian priesthood designed and developed religion and transcendence—we must first ask what came before, how it was transformed, and to what degree. To address this, I developed the first typology of its kind (see Table 1, above), outlining six distinct RMS epochs. I am glad I did: it clarifies our species’ path, reduces bias, and reveals extraordinary insights that strike at the very heart of our subject.

RMS-1: Hunter Gatherer Animism

The first RMS, when hunter-gatherers (HGs) were the predominant social form, is by far the most important. Anthropology and ethnography reveal that HGs encountered reality directly, unburdened by the distorting weight of abstraction. They lived attuned to natural cycles, rooted in the sensory world, bound to their groups, and at home within themselves. Life was demanding, but it was also coherent, practical, and full of meaning. They were ontologically oriented in the cosmos—dwelling within a Field of Relationship (FOR), where existence itself inherently meant belonging and where all things stood in relation and equality.

Animism was a worldview that both expressed and sustained their values. In it, nearly everything was alive, imbued with what we might call a ‘soul’—yet without the transcendence or teleology imposed by later systems. In such a world, where all things were interconnected, equally valued, and continually renewed through custom and practice, HGs stand out as among the most integrated humans—psychologically, spiritually, and socially—by most measures of well-being.

Another reason for its primacy is duration: 286,000 years. Ninety-five percent of our species’ time was lived in animistic spirituality. By comparison, monotheism’s two millennia are a mere blink—outweighed by a ratio of 143 to 1. Just as important, most of our genetic traits took shape during this time. The patterns of HG life – cooperation, empathy, non-violent cohesion, affinity for nature, relational knowledge, and thought by embodied metaphors – are innate to our species.

All this is well documented in social psychology, anthropology, archaeology, and biology. Proponents of capitalism, civilization, and radical Protestantism deny it. Accuracy has never been their concern; their ideology thrives on distortion.”

And so, this epoch of RMS—the longest and most formative in human history—remains not only overlooked but actively suppress it.

RMS–2: Chthonic Spirituality

This epoch represents a new level (B) of RMS, distinct from the animism of Level A that came before. Lasting roughly 8,500 years in the ANE, it spanned the entire transition between Stage II and Stage III.

While it is important to understand why this epoch displaced the first RMS after its long reign, space allows only a brief discussion. The most obvious change was the gradual shift from nomadic HGs to sedentary farmers. Animism proved remarkably resilient, persisting across parts of the ANE from about 12,500 to 9,500 BCE. By then, full-scale agriculture was established, and animal domestication had begun.

These two developments shaped the new RMS. What I call chthonic spirituality characterized the rest of the transition period: spirits were believed to inhabit particular places and fill specific roles. The previously animated world was thus reorganized into identifiable presences—not yet gods, but person-like forces charged with keeping the surrounding world and cosmos in order.

These spirits were primarily female, a crucial fact for our purposes. While scholars rarely emphasize it, the associations of earth, soil, fertility, and abundance—essential to agrarian life—were typically bound to female essence, or the O/F. This predominance is understandable, yet the 5,000-year span when feminine worship held sway remains largely overlooked. In particular, scholarly neglect of the Ubaid period immediately preceding civilization has led to underestimating the scale of rupture: within only five centuries, the O/F was not simply sidelined but directly attacked. Such a profound reversal demands sustained explanation, but scholarship has yet to provide it.

And despite emerging practices with adverse effects—animal domestication, hierarchical ordering in parts of the ANE, and the first management of surpluses—the chthonic feminine spirit still served as a broadly protective presence in the small farming villages and towns that dotted the Sumerian plain before civilization arose.

The Third RMS: Religion in Civilization

While God may have created heaven and earth, it is certain that the Sumerian priesthood created the first religion. Because we still live in its shadow, the shift from chthonic spirituality to institutional religion can seem natural, even inevitable. Yet it was unprecedented: for the first time, an RMS was deliberately designed and institutionalized—an invention of staggering consequence.

The male priesthood was still defining its role at the onset of the GRP around 3600 BCE. Only a few centuries earlier they had been managers of surplus grain. As the SCS accelerated and male identity grew ever more bound up with dominance, these administrators envisioned a new horizon of power. By positioning themselves as the custodians of religion, they could transform bookkeeping into authority. Life in the new, anonymous cities was bewildering; if the priesthood explained these changes from a cosmic vantage point—and claimed to provide order—they could secure control over people and the SCS.

Characteristics of RMS-3

Religious life was centralized in temple complexes—the earliest prototypes of later ziggurats—rather than in the diffuse chthonic presence of the landscape.

Height and verticality became new markers of power and knowledge. Priests were literally elevated above the community and symbolically closer to the newly prominent “named” gods.

Within the temple precincts, rites and rituals were formalized to surround religion with mystery and awe, reinforcing priestly authority.

Sacrifice, offerings, and festivals grew increasingly regulated, with heavy emphasis on precision, order, and correctness.

Women were excluded from priestly leadership, and this exclusion was reinforced by the marginalization of feminine chthonic spirituality—carried out in part through the priestly denigration of goddesses.

Male gods and heroic myths gained prominence, aligning cosmic order with male authority in society.

Temples doubled as administrative hubs, entwining priestly religion with urban governance and economic management.

Sharper dualisms and boundaries were introduced—sacred/profane, priest/laity, male/female—structuring both religious and social life. (The good/evil polarity developed more fully only later, in Mesopotamian and Hebrew systems.

Individuals still related to personal gods, but these were subordinated to the higher gods of each city, securing compliance with the broader religious–political order.

Religion ceased to be embedded in daily life. It became abstracted, transcendent, and mediated through symbols, texts, and institutional control.

These features of RMS-3 cemented priestly authority, regulated the daily lives of the masses, and advanced civilization’s broader agenda. The array of new practices and modes of thought reshaped not only religion but the entire SCS. Abstract forms of reasoning multiplied and grew ever more complex. The further a chain of thought extended from lived experience, the harder it became to grasp directly—and the easier it became to smuggle in and normalize decadent values.

*****

Had these distortions ended in the Ancient Near East, humanity might have overcome that beginning. Instead, they endured and grew stronger. Why, then, is this history—these monumental events—treated as irrelevant today? Religion was born here; it redirected the trajectory of our species. For nearly 300,000 years the psyche was whole; for the last 6,000 it has been fractured.

The absence of a typology of RMS may stem from this very discomfort. Such a framework would reveal too much about us—about what really happened. Perhaps reality is so depressing that we feel compelled to transcend it.

Transcendence and its Pervasive and Enduring Impact

The Habit of Transcendence

Is reality depressing? Under civilization, yes, it often is. This helps explain why the urge to escape is so popular. Life is either too difficult, or we feel unable to face it, so we search for ways to go over or around it: more money, good luck, salvation, addictions, the runner’s high, New Age laws of attraction, a new romantic partner, the promising candidate, the afterlife, inner peace, pure consciousness—always more, bigger, better, faster, higher.

Transcending the moment by imagining other possibilities can certainly be healthy. I’m a fan of daydreaming because it resists the capitalist imperative—and because imagination brings its own rewards: hope and visions of a better world. The trouble begins when these qualities harden into a permanent condition, where the future is glorified, and the present world is cast off as little more than a morbid past.

This everyday habit of escape has a long history. What may feel like a personal tendency was, in fact, built into civilization itself. Full-scale, insidious transcendence has been part of life ever since the priests wove it into their new religion more than 5,000 years ago. If that seems doubtful, it is only because it has become so commonplace—like trees in a forest or the air we breathe.

The Purpose of Transcendence

This relentless mechanism did not appear out of nowhere. It always carried a certain allure—the brilliance of the night sky, the mystery of distant mountains, the sense that something important might lie “out there.” In early civilization, though, it took on sharper social and political form. Elites stood literally above others: taller than commoners, living in raised or more imposing houses; men physically taller than the women and children they dominated. With the Great Ruptures Period, this everyday verticality was transformed into religious power. The named gods were no longer chthonic presences woven into the landscape but were repositioned “in the heavens,” far above. Massive temples now loomed over the crowds, their height dramatizing distance and superiority. Priests stationed at the top became the visible link to the divine—closer to the gods, elevated above the people, perfectly placed to symbolize their exclusive role as intermediaries with the “beyond.”

Soon enough, “higher” came to mean better—more refined, important, sacred, and unique. By contrast, the lower classes were expected to accept their plainness and “lower” status and to follow commands without question. Yet sealing in privilege and enforcing compliance were not the only, or even the most decisive, purposes of early transcendence.

Recall that two of the four ruptures delivered the first direct attack: goddesses were named only to be undermined, and women were subjugated through demeaning gender roles. Both moves targeted the Ontological Feminine and, through it, the very ground of existence. Those who dismiss ontology as irrelevant today should ask why the ancient priests were so intent on suppressing it. They knew it was bound up with the chthonic feminine spirits that had predominated for millennia. Job one was to break that bond.

But the Uruk priesthood knew that wasn’t enough to secure their rule. They designed the next two ruptures—religion and transcendence—to overwhelm an even more powerful adversary: reality itself, especially the physical world. In early civilization, life and nature were far more immediate and influential than they are for us today, sealed in cubicles, apartments, or—more often—cardboard boxes on cold sidewalks. People then lived in direct contact with nature (though less than hunter–gatherers 9,000 years earlier), which made them harder to deceive. You could not convince a farmer that a rock was a vegetable. But a doomscroller might believe almost anything, because the gap between lived reality and internet propaganda has grown too wide for truth to hold.

So physical reality became the next target for elimination. This was no easy task, given the Sumerians’ familiarity with it, so the process unfolded gradually over centuries. The new religion’s turn toward a non-material world was the first step, but transcendence made the decisive move. By placing the gods above, they became ethereal, and communication with them grew abstract. Declaring the temple sacred space was, in effect, a way of privileging emptiness over substance.

Physical reality never vanished, of course, but our sense of it was reshaped until it seemed hazy and remote. Priesthoods—and later the thinkers we call philosophers—kept steering this shift. Philosophy itself can act as transcendence: abstruse language that distances the reader, especially when it argues the invisible is more real than the visible.

There is no clearer example than Plato, who claimed the “eternal forms” were far superior to their physical counterparts. The form of a table, for instance, was idealized, made timeless, and rendered unchanging—three ways to diminish reality in one stroke. He went further by elevating “the Good” above Being itself, replacing immanent relationality, grounded in physical reality, with an abstract, elusive conception that would dominate for the next 2,200 years. If we wonder how such bizarre formulations could not only be accepted but become central to daily life—especially in the West—the answer lies in long conditioning: three millennia of transcendent thinking between the GRP and Plato had softened people until it seemed almost natural.

Plato, however, separated transcendence from religion for the first time—and the last until the modern era. Greek and later Roman pagans tolerated this, having grown accustomed to metaphysics detached from gods. For Christians, though, such separation was intolerable. Once Christianity became the dominant religion of the Roman Empire, its thinkers worked to reunite the two strands. Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE) and, later, Pseudo-Dionysius (late 5th–early 6th c. CE) completed the synthesis by taking Plato’s formula and replacing “the Good” with an eternal, omnipotent, unchanging God.

Philosophy and theology have been central to spreading transcendence and the illusions that still bedevil us. Across civilization this tendency only deepened, reaching new extremes in the modern era (1492–1918). Even now we privilege conscious thought and belief over the body, instincts, emotions, and the unconscious.

Hunter–gatherers, by contrast, had no concept of purity or impurity, no sacred/profane, no good versus bad—none of the dualisms we now take for granted. Such categories did not exist in nature; they were alien to their way of life. Nor did they need the practices of civilization—those elaborate devices meant to terrify us or soothe us back into our postmodern cages.

Tracing Transcendence Through Etymology

The etymology of words—especially those tied to enduring practices and customs—offers a clear view of how ideas evolve and continue to shape thought. The concept itself took root about 5,000 years ago among nomadic Indo-European steppe pastoralists. Their root expression (terh- + skand) meant simply “to climb over” or “to step across,” evoking a physical crossing rather than a metaphysical one. The Sumerians, by contrast, already practiced it through ritual and architecture—most strikingly in the ziggurat—though they had no single word for it.

Greek terms for “above,” “beyond the limit,” or “boundless” gained full metaphysical force only with Plato around 370 BCE. His use of “beyond” turned the notion into an explicit philosophical concept: a higher, non-physical reality at the core of his idealist system. Such practices were already embedded in ritual and culture, but Plato gave them intellectual permanence. More than anyone else, he made it the cornerstone of respectable Western philosophy.

The Romans, by contrast, first coined the term transcendere, using it both literally (“climbing across”) and figuratively, as in Cicero’s phrase “exceeding the limits of law.” Characteristically pragmatic, pagan Rome showed little interest in metaphysical abstractions like idealism.

When Augustine integrated Platonic thought into Christian theology, he recast transcendere as the soul’s ascent from the mutable, earthly world toward the eternal God “above” creation. That sense has endured to this day. A secular line emerged much later: in Kant, it referred not to God but to the conditions of thought beyond experience, and in later philosophy it came to mean self-overcoming or the push to exceed ordinary human limits.

The details differ, but the direction is constant: thought kept drifting away from the world itself.

Language Steeped in ‘Beyondness’

Words, phrases, idioms, metaphors—expressions of going “above” or “beyond”—permeate how we speak, think, and imagine. We reinforce them almost every time we open our mouths. Over the past year I have tried to avoid words that state or imply transcendence, yet I have made little “progress”—a word that itself smuggles in the same logic. The effort only shows how deeply these habits are embedded in language.

Since the terms are endless, I will group them into categories with a few representative examples.”

List of transcendent terms

Active transcending

Hierarchy & Rank: master, high priest, noble

Social Status: high society, high-born, good breeding

Comparative Superiority: better, higher, superior, advanced

Moral / Spiritual Elevation: rise above, turn the other cheek, enlightened

Authority Figures: priest, healer, prophet, thought leader

Otherworldly realms

Spatial Realms: heaven, higher plane, the beyond

Temporal Realms: the future, destiny, utopia

Interior Realms: eternal soul, mystical union, pure consciousness

Abstract ideals

Truth, Justice, the Good, the Forms

Permanence: eternity, immortality, unchanging essence

Perfection: flawless, pure, absolute, ideal

Embodied transcendence

Ascent & Height: stand tall, hold your head high, rise to the occasion, look up to someone

Purity & Cleanliness: pure heart, clean hands, washed of sin, spotless

Containment & Separation: mind over matter, control yourself, keep it together

Disembodiment: out-of-body, higher self, mind over matter

Finally, transcendence fuses with dualistic thinking to generate its negative counterpart. Elevated terms for the favored group inevitably produce pejorative labels for those deemed lesser:

Dualistic oppositions

Low Status / Class: low breeding, commoner, peasant, rabble, underclass

Moral / Spiritual Fall: fallen, debased, base, beneath, impure.

Intellectual / Skill Deficiency: primitive, underdeveloped, substandard, crude

We can now see how the mechanism of transcendence divides us into opposing groups of putatively good and bad while misleading us with false claims and illusions. It must be rooted out—of language—of thought—of behavior—of action.

The Last Three RMS Epochs: Religion’s Changing Face, Enduring Core

Now we turn to the last three epochs of religion in civilization. As we trace their evolution, note how each one preserves the same underlying structure of religion that still shapes us today.

RMS – 4: Male Sky Gods

The Named Gods epoch lasted around 1100 years (2500–2350 BCE), the shortest of the six. By then the goddesses had been domesticated – their wild feminine essence the priests so feared no longer posed a serious challenge to civilization or elite authority.

As if to punctuate the shift, the epoch of the male sky gods opened with the rise of the first empire in Akkad. From that point forward—including in today’s American empire—this form of sociopolitical control has persisted. The Akkadians had no template to follow: military conquest is a crude and costly way to dominate vast regions, though this calculation rarely seems to matter. The creation of standing armies, now newly necessary, produced a professional soldier class that deepened the dehumanization of the male role.

Men were now required not only to carry out violence but to embrace it, even as they were hardened against its effects. This demanded intensive interior management of a rapidly deteriorating psyche—a rigid system of repression. War, violence, and male control became central to imperial organization. Male sky gods ruled from above, cementing patriarchy and absolute control. Abstraction, essential to managing empire, became a male prerogative, echoing the abstract concepts needed to believe in and propitiate a harsh, angry, distant sky father.

RMS-5: Monotheism

Our typology has traced the movement from animism, through chthonic spirituality, to the early religions of the Ancient Near East, and then to later epochs in Europe. The emphasis here is on the West—both as the main conduit of civilization-induced trauma over the past five centuries and as the driving force behind today’s neoliberal globalism.

Monotheism as it shaped the Western psyche arose from the Hebrews and the Homeric strand, and a Christian–Platonic synthesis carried it into a sullen adolescence where it has remained ever since.

But still a prodigy. Endless sophisticated parlance has justified, praised, and glorified the fusion of Christian monotheism with Western practices and ideals. Yet a close review of the evidence—stripped of mythography—offers no basis for treating it as the highest form of religious development:

Monotheism has been more soaked in blood and misery than earlier forms. Christianity and Islam especially have spread through conquest and ideological expansion since their origins.

There is nothing innately superior in their theology, though one could argue Islam is less burdened than the other two by ressentiment, guilt, sin, and sacrifice.

Monotheism divides into two camps: Christianity and Islam, historically opposed. Yet, as noted in the last essay, Islam has long been cast in the West as the dark, foreign, and suspicious ‘Other’ of the weak, effeminate East—an opposition through which the West has defined and bound its own sense of ‘Us.’

Christianity is especially unstable, nearly impossible to define given the Catholic/Protestant split and, among Protestants, some 20,000–45,000 sects. Which of these counts as the “ideal” form of monotheism?

By contrast, the two earliest RMS epochs are the only ones linked to a healthy, integrated psyche. No theological or philosophical rationalization can change that. Yet comparison is never made—showing again the need for a typology such as mine.

RMS-6: Capitalist-Sociocultural Monotheism

Today, every society lives within some amalgam of monotheism, neoliberal capitalism, pathological individualism, and the decadent values of late-phase civilization. The balance of these elements varies from country to country, but the ingredients themselves rarely change. I will not attempt to prove this here; it is enough to note that disproving it would be far harder than demonstrating it.

Speaking primarily about our focus—the Western mythos—it no longer matters whether one calls oneself “religious” or not, or whether one agrees or disagrees—this is you: the fractured remnant of psyche, the postmodern self.

We are all locked into a world even more “hyperreal” than when Baudrillard coined the term in Simulacra and Simulation (1981), at the dawn of the neoliberal era. We now face copies of copies of copies—an endless cascade of abstractions with neither origin nor end. In such a world we drift without a rudder, grasping for authenticity, unaware that it can no longer be found.

And that was precisely the purpose of those Sumerian priests 5,500 years ago. They could never have imagined how successful their four ruptures would be—or that they would still be operating today. Yet they would be puzzled by our modern version, steeped as it is in hyperreality. In the ANE between 4000 and 550 BCE, as civilization first took shape, priesthoods and political elites were blunt about their aims. Power, values, and compliance were communicated directly, and myths were not metaphors but lived truths.

Today, in the second half of civilization (550 BCE to the present), ideology and propaganda have become so seamless that we neither see them nor recognize our own thoughts arising from them. We no longer even know that our myths are real. And our ignorance is carrying civilization toward terminal collapse.

Other than the indirect and deceptive nature of our present controlling ideologies, our current meaning/relationship system remains markedly similar to civilization’s first, repeating the same structures under new names.

Principal similarities between civilization’s first religion and today’s version

Ritual centrality — discipline through repetition.

Sacred/profane split — severance from nature, spawning dualisms.

Denigration of nature and the physical.

Priestly mediation — gatekeeping the divine.

Canonical texts — fixed law, memory control.

Prayer and sacrifice — codified obedience, tribute.

Hierarchy — mirroring state and elite power.

Patriarchy — repression of the O/F.

Transcendence — abstraction over immanence, illusion over reality.

Religion–power nexus — compliance and legitimation of civilization.

Temple as institution — bureaucracy and monopoly.

Resource concentration — tithes, gifts, ownership, wealth retention.

Missionizing — gaining converts while securing the faithful.

Yes, there are differences — important ones — but the fundamental structure remains the same. And yet our transcendent intellectuals — those who revel in abstractions — have largely refused even to comment on it, let alone identify it. This leaves the rest of us adrift. Not grasping how the ancient past has shaped us is serious enough; failing to see that its very mechanisms of destruction — the four ruptures — have only grown stronger and continue to govern our lives today is folly, pure and simple.

In the next two essays we will turn to the second half of civilization, to the creation of the Western mythos — the monstrous offspring of the monster we unleashed 6,000 years ago.

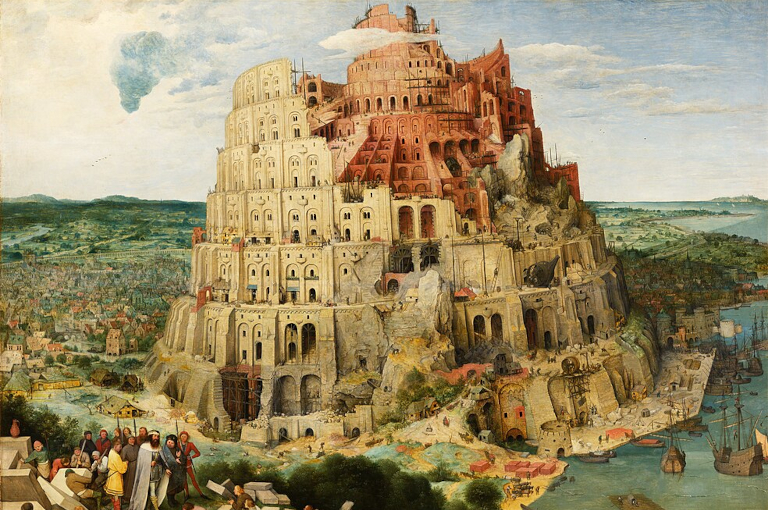

By Pieter Brueghel the Elder – Levels adjusted from File:Pieter_Bruegel_the_Elder_-_The_Tower_of_Babel_(Vienna)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg, originally from Google Art Project., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22179117