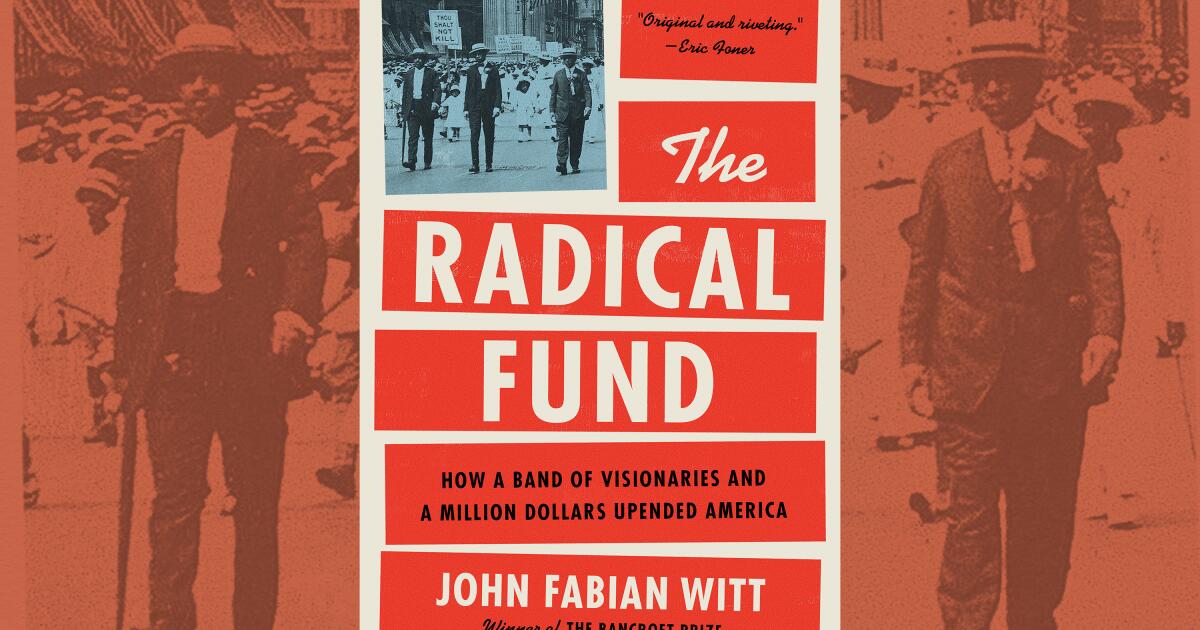

Reading Yale professor John Fabian Witt’s ninth and newest book, “The Radical Fund: How a Band of Visionaries and a Million Dollars Upended America,” I was reminded of Angelica Schuyler’s search in “Hamilton” for “a mind at work.” There is a great mind at work in this book; Witt has meticulously uncovered and documented the lost history of one of the United States’ most efficient charitable funds. With incredible detail, he has reconstructed the ways a modest fund endowed by a reluctant heir managed to reshape American civil rights in less than 20 years.

Starting with the life stories of the founders of the American Fund for Public Service, Witt immerses us in parallel tracks hurtling forward into the heady 1920s, when an exclusive few hoarded American wealth while the rest toiled painfully and daily. In an eerie echo of today, a post-pandemic president promised to restore “real” American values while the country came to blows over racial unrest, shameless disinformation activity, crumbling labor unions, income inequality and censorship. Witt dives deep into this social setting, revealing not only big-picture moments and movements but also the people and legal decisions that created the environment for this crisis of American life.

The American Fund — or simply the Fund, as it came to be known — had been reluctantly established in 1922 by Charles Garland, who had inherited $1 million but refused it on ethical grounds. Amid the uproar over his decision came letters from Upton Sinclair urging Garland to put the money to good use by endowing a fund for the good of mankind. (Sinclair, author of “The Jungle,” is only the first of many household names who get entwined in the story of the fund, while the original donor is largely forgotten today.) When Garland finally agreed to do so, he requested only that the funds be disbursed “as quickly as possible, and to ‘unpopular’ causes, without regard to race, creed, or color.” Accordingly, the fund was designed to spend itself down to zero by gambling on new ideas and experimental projects.

With these marching orders, fund directors awarded grants to diverse efforts like labor organizations, studies on Southern education, civil rights court cases, anti-lynching campaigns, legal defense funds, combating misinformation through better journalism, the legalization of birth control and more. They subsidized famous organizations like the National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People, the American Civil Liberties Union and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Funds were allocated to radical leftist publications such as Cultura Obrera and films such as Max Eastman’s 1937 documentary, “Tsar to Lenin.” Through partial grants, the fund ended up involved with legendary American court cases like the Scopes trial, the Ossian Sweet trial, Brown vs. Board of Education, the Sacco and Vanzetti murder trial and more. If there was an issue on the vanguard of civil liberties, the fund and its directors were aware and considering it.

A professor of American legal history, Witt has written a book that is at its most nuanced when he’s laying out the details of trials and case law, as well as their roots and impact. But not only does he measure the influence of the fund, which dissolved in 1941, he also documents the directors who advocated for various causes and the arguments that went into major funding decisions. By piecing together the conversations, rivalries and romances of these passionate advocates, he shows us the ways that they were real people doing the best they could with the information they had. Their goal was to make life better for millions of Americans, but the path forward was not always clear.

In his conclusion, Witt examines the impact the fund had on the lives and legacies of its directors. Even with the benefit of hindsight, they could still see what “a tough job” it is “spending a million or two well.” Even though by all measures of a successful nonprofit, with a mere $67,000 spent on overhead in 19 years compared to $1.85 million gifted, its directors didn’t always feel like they had made good decisions, that perhaps the money could have been better spent on different causes.

But they did quite a lot of good. As Witt points out, the fund’s unique priority to focus on “unpopular” causes allowed its directors “to put issues on the political agenda that elected officials had skirted time and again, and which unions and membership organizations alone could not sustain.” They could fund — and did — projects that weren’t commercially viable, that went against the status quo and the interests of the powers that be. As I read, I found myself repeatedly thinking, “If only this fund still existed.”

Therein is the important crux of this book. Witt seems to be showing us, in exhaustively documented detail (including pages of appendices, budgets and endnotes that usually run to 50 or more per chapter), how badly we need efforts like this again — and how comparatively modest efforts can go such a long way. Repeatedly, he compares Garland’s Fund to bigger charitable organizations, like the Rockefeller Foundation, and shows that with a minuscule fraction of the funding, Garland’s Fund touched at least as many lives. Early in the book, Witt examines what the concentration of money in the richest 10% of Americans in the 1920s “seemed to be doing to American democracy.” The super rich bought coverage, shaped public opinion and ensured the future was theirs. It’s a state of affairs that bears so many similarities to today that it would be laughable if it weren’t so concerning. In his conclusion, he points out that a million-dollar inheritance doesn’t go as far as it used to, but he suggests it can still do quite a lot. He stops just short of handing us a blueprint.

A hundred years ago and today, money is power. Like Upton Sinclair, Witt suggests to us all in the last line of his book that “the opportunity presents itself once more.”