One of the most interesting funding deals of the fall just happened: the Silicon Valley chip designer NVIDIA invested an undisclosed sum of money in QuEra, a Boston startup that is building quantum computers.

With the announcement last week, NVIDIA joins Google and SoftBank in betting on QuEra ŌĆö and solidifies QuEraŌĆÖs spot as the best-capitalized quantum startup in Massachusetts, with more than $275 million raised since it was founded in 2018.

ItŌĆÖs also NVIDIAŌĆÖs most notable local move since March, when it announced it would set up a new research center in the Boston area, the NVIDIA Accelerated Quantum Computing Research Center. QuEra and NVIDIA plan to collaborate using the new centerŌĆÖs resources, according to a press release last week.

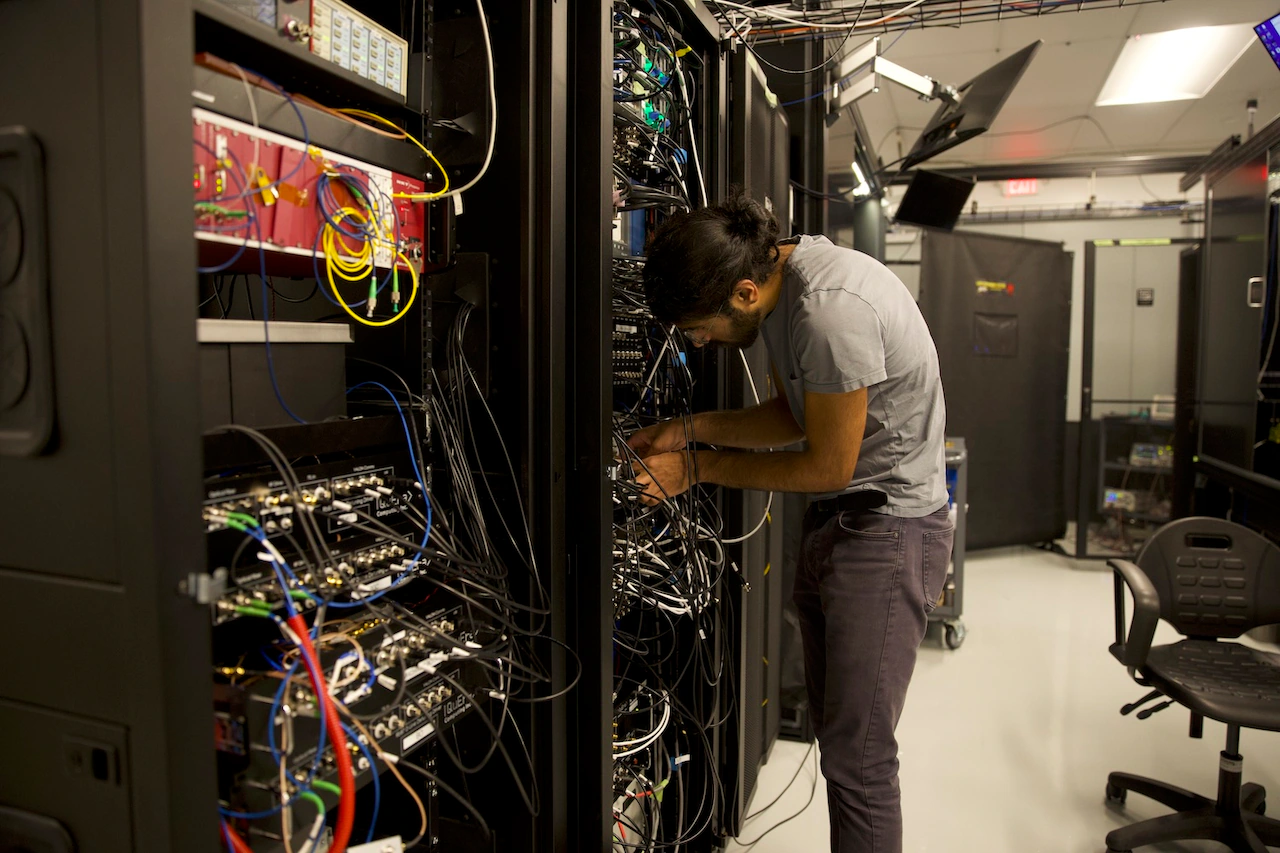

I dropped by QuEraŌĆÖs offices over the summer to catch up with Yuval Boger, the companyŌĆÖs Chief Commercial Officer, and see the computers they are building and operating. One of them is already available to people who want to use it on AmazonŌĆÖs ŌĆ£BraketŌĆØ cloud service.

Quantum vs. traditional computers

Traditional computers rely on millions or billions of switches called transistors, and those switches can be in either an ŌĆśonŌĆÖ or ŌĆśoffŌĆÖ state. This binary encoding (0s and 1s) underpins all of todayŌĆÖs computers. In contrast, quantum computers are built around quantum bits, or qubits. Qubits can exist in a ŌĆ£superpositionŌĆØ of both the 0 and 1 states at once, as well as any quantum state in between.

How sophisticated is this stuff? QuEraŌĆÖs qubits are individual atoms of the metal rubidium, controlled by lasers.

Because of that, many proponents of quantum computing say that it will be better at simulating complex phenomena ŌĆö like weather, the way drugs behave inside a personŌĆÖs body or the chemical reactions inside a battery. But todayŌĆÖs quantum computers are still somewhat error-prone and rough around the edges.

ŌĆ£Conventional wisdom these days is that in two or three years, quantum computers will be sufficiently strong to solve some chemistry and material science problems,ŌĆØ Boger said. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs not surprising that itŌĆÖs chemistry and material science [first], because these are problems that exhibit quantum mechanical properties. How does a molecule behave, and so on.

ŌĆśQ DayŌĆÖ is on the horizon

ŌĆ£Maybe in five years, youŌĆÖll be able to use a quantum computer to optimize your financial portfolio better. Maybe in 10 or 20 years, youŌĆÖll be able to, for better or worse, break the worldŌĆÖs encryption using a quantum computer,ŌĆØ he added.

ThatŌĆÖs a problem that many governments and corporations are already thinking about. They call it ŌĆ£Q DayŌĆØ ŌĆö the day when someone somewhere develops a powerful enough quantum computer that can break encryption systems. The U.S. government ŌĆö and many major corporations ŌĆö have identified it as a major cybersecurity threat.

When I visited QuEraŌĆÖs office, I had to sign an attestation that I was a citizen of the U.S. ThatŌĆÖs because quantum computing technology, and exports of it, are controlled by the Department of Commerce as vital to the countryŌĆÖs national security.

ŌĆ£We are building some of the worldŌĆÖs most advanced quantum computers and … a lot of people want to understand whatŌĆÖs in them.ŌĆØ

Already, Boger said that the early users of QuEraŌĆÖs quantum computers have been trying to solve problems such as the best placement for electric-vehicle chargers and a better understanding of the effects of new drugs when clinical trial populations are small.

Boston is a quantum computing hotspot

ŌĆ£The quantum computing ecosystem in Boston is really one of the hotspots in the U.S.,ŌĆØ Catherine Lefebvre said. ŌĆ£With all the experts at MIT, Harvard and other top universities ŌĆö you have a lot of investors too ŌĆö there are all the ingredients for a very strong ecosystem.”

Lefebvre tracks the industry as a senior advisor to the Open Quantum Institute, which aims to ensure that quantum computing is developed ŌĆ£for the benefit of humanity.ŌĆØ

QuEraŌĆÖs technology ŌĆ£is pretty advanced, and theyŌĆÖre moving fast and steadily,ŌĆØ she said. But compared to other companies, they are still a ŌĆ£small player,ŌĆØ with a small team and facility.

But Lefebvre said that ŌĆ£it is way too early to pick a winnerŌĆØ among the many startups ŌĆö and larger companies, such as IBM and Microsoft ŌĆö that are developing quantum computers.