Copyright The New York Times

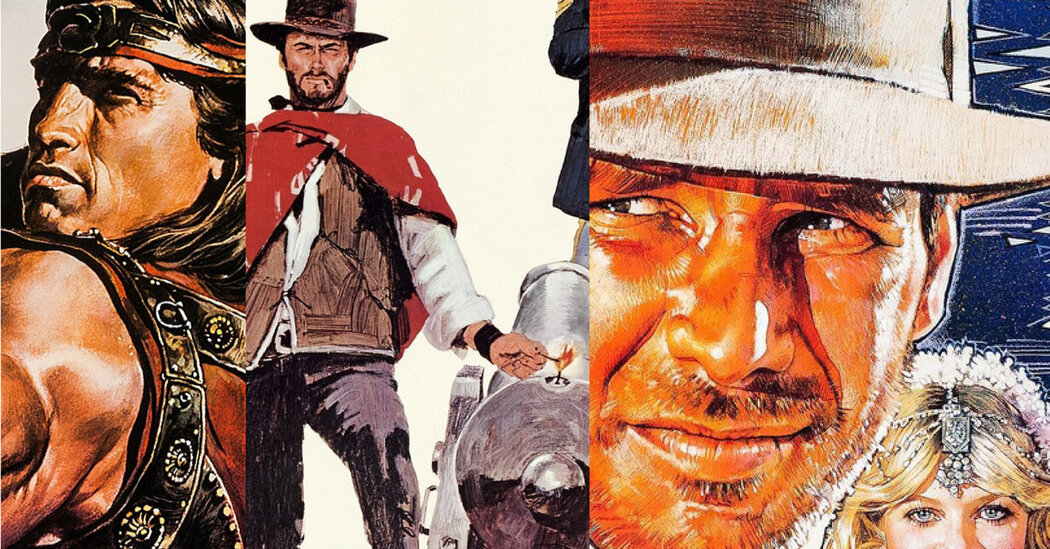

A survey of the combined portfolios of Drew Struzan and Renato Casaro amounts to a tour of blockbuster cinema for more than half a century: the “Star Wars” franchise, the Indiana Jones movies, the “Man With No Name” trilogy, Rambo, Harry Potter, the Terminator, the Muppets. Their carefully composed, painstakingly crafted illustrations often became our default impression of those films and their stars, beyond anything captured on the celluloid itself: Marty McFly checking his watch in disbelief at the door of the time-traveling DeLorean on Struzan’s “Back to the Future” poster, Casaro’s striking pose of “Conan the Barbarian” with his sword aloft, the chain of tweens and teens hanging from a precarious height in Struzan’s art for “The Goonies,” the operatic heroes and villains of Casaro’s “Flash Gordon” poster. You may not know their names like you know the stars or even directors of those films, but for many, Struzan and Casaro’s posters are indelible images of heroism, adventure and Americana, irrevocably embedded in our collective moviegoing. Struzan’s posters for the Indiana Jones series, for example, clearly capture the distinctive visage of its star, Harrison Ford, and the recognizable details of his characterization of Dr. Indiana Jones (the battered fedora, the weathered jacket, the ever-ready bullwhip). But Struzan augmented those details with the ornate flourishes of an impressionist painter. Arnold Schwarzenegger was one of Casaro’s most frequent subjects. (He created not only the “Conan” posters, but also art for “Red Sonja,” “The Running Man” and “Terminator 2”.). The artist brilliantly captured the real, hard chisels and lines of Schwarzenegger’s carefully crafted body, while framing him like a Greek god. (“Schwarzenegger was the perfect man to paint,” Casaro told The Guardian in 2022. “He had a tough expression. His face was like a sculpture.”) But there were also vast differences in their style and output, many of them rooted in the wide gulf in their backgrounds. Casaro was an Italian, born in Treviso in 1935, and he came of age professionally during one of that country’s golden eras of cinema. His images helped define that era, not only with his memorable posters for such groundbreaking Sergio Leone spaghetti westerns” as “A Fistful of Dollars” and “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly,” but similarly eye-catching art for genre pictures like Mario Bava’s “Danger: Diabolik” and Umberto Lenzi’s “Eyeball.” Hollywood took note, and began hiring him in 1966 (first for John Huston’s “The Bible: In the Beginning”), and the bold imagery and clean lines of those early posters remained a potent utensil in his artistic tool kit. Struzan, on the other hand, was born and raised in Oregon City, Ore., and his American-as-apple-pie background informed his eye as an artist. Just as important was his entrance into the world of illustration, not creating movie posters, but album covers — arguably a field in which encapsulating a work of art in a single visual concept is even more vital. His work for Alice Cooper, Black Sabbath, the Beach Boys, the Bee Gees and Earth, Wind & Fire led to jobs in the movie poster field, initially for low-budget B-movies like “Empire of the Ants,” “Squirm” and “Food of the Gods.” Those one-sheets led his fellow poster master Charles White III to ask Struzan for an assist on the art for the 1978 rerelease of the previous year’s megahit “Star Wars”; that image, known in collector’s circles as the “Circus” poster, launched Struzan into the big leagues of blockbusters like “The Muppet Movie,” “Blade Runner,” “E.T.” and the “Star Wars” sequels and prequels. Struzan was perhaps at his best with large casts of colorful characters. Whether the film was a big-budget behemoth of the “Harry Potter” variety or a disreputable, lowbrow comedy like the “Cannonball Run” or “Police Academy” series, he could artfully arrange all of the players without ever creating a composition that overwhelmed the eye. Casaro could likewise create whole worlds in a single frame, as he did with his distinctive one-sheets for David Lynch’s “Dune” and the James Bond picture “Octopussy.” But both artists could also masterfully dispense with such complexity and create images of startling simplicity and beauty — Casaro’s gorgeous yet stark art for Bernardo Bertolucci’s “The Sheltering Sky,” for example, or Struzan’s brilliant use of dark shadows and blasts of light in his unforgettable poster for John Carpenter’s “The Thing.” They weren’t just talented; they were also versatile.