Copyright thejc

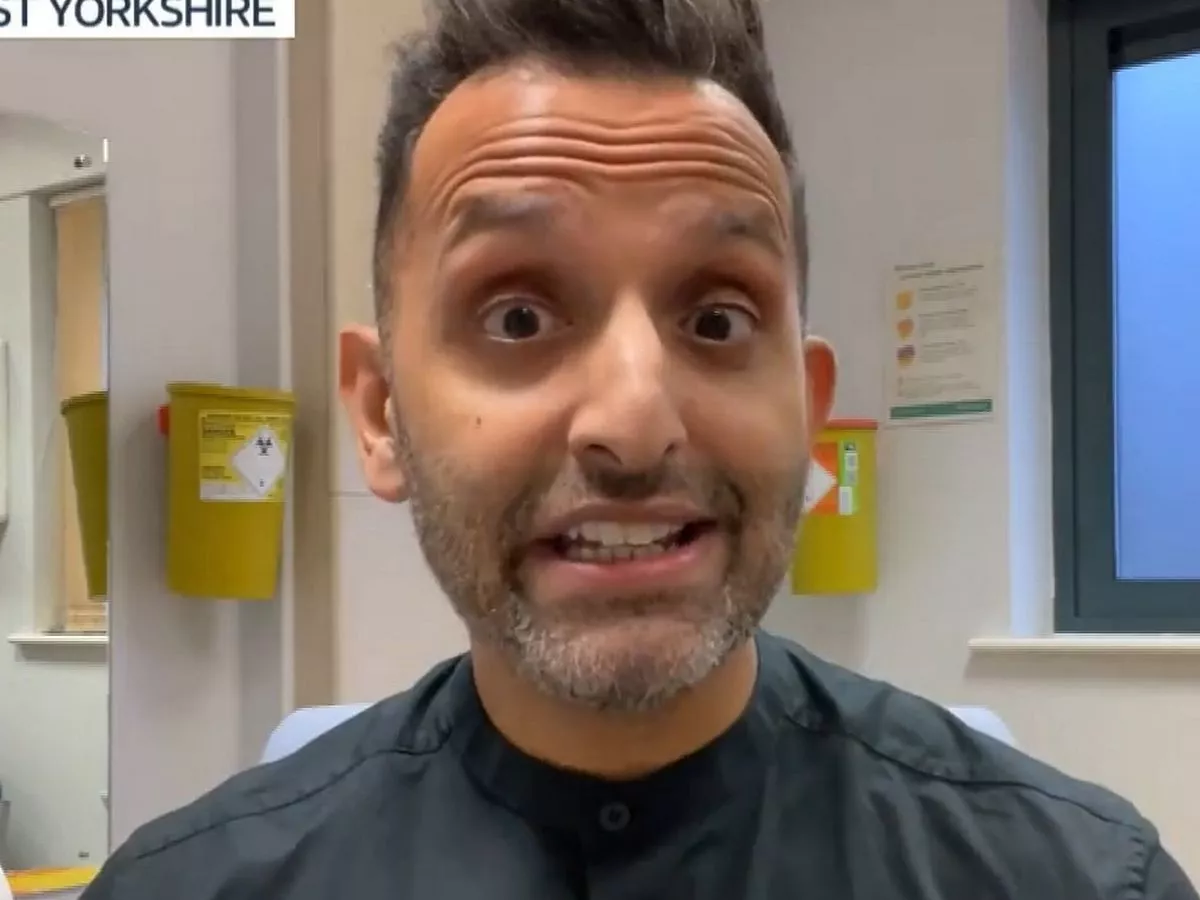

Measles is back in town and Hackney, with its large Charedi population, is top of the league table for cases while bottom for vaccinations. Worried local doctors are redoubling their efforts to get children inoculated. And they think – or at least hope – it’s working. Among the strategies they are using is offering to come to people’s homes to vaccinate their families, and engaging with local rabbis including the respected and much-loved Rabbi Herschel Gluck. “There is a great need to help people understand the importance of vaccines and how they save lives,” he says. “Much more can be done to encourage them." One doctor who has already done much encourage locals to get jabbed is Tehseen Khan, of Stamford Hill’s Spring Hill practice. His approach, he says, is to try to gain people’s trust rather than lecture them about statistics. When face to face with a sceptical parent, Dr Khan tries to find points of agreement. “I try to align our common purpose, which is to protect the child,” he says. “That automatically helps the parent realise that it’s not going to be a confrontational conversation.” I think it may take a long time to change mindsets in the community, but I see any vaccine given to a child who wasn’t previously protected as a win It also helps to avoid being judgmental, and to offer a balanced view of the possible risks, he says. “If you just tell them the benefits, then that raises their suspicion more when they get their child vaccinated and they’re a bit ill for a couple of days. So, it’s about offering the opportunity to answer any questions, but also not pushing the vaccine too hard and being transparent.” Most of all, it’s vital to know when it’s pointless to try, because the patient or parent is one of the five per cent who are firmly anti-vax. “The evidence is you’re not going to be able to say anything to them to convince them otherwise. So, there is a sense of picking your battles,” he says. All this matters because according to official figures, from January to mid-September 2025 there have been 772 measles cases in England, of which 99, or close to 13 per cent, were in Hackney. And that may well be an underestimate because not all sick children get seen by a doctor. What is sure is that measles is a highly contagious virus which can lead to serious problems, especially in people whose immune system is compromised. Since the beginning of 2024, seven deaths as a result of the disease have been reported in England. Sixty years ago in 1965, that number was 115, and 80 years ago, in 1945, it was 729. There’s one reason why the death figures have plummeted: vaccination was introduced in the UK in 1968 followed by the combined MMR inoculation in 1988. But for vaccination to be effective, you need “herd immunity”, a kind of blanket coverage, to prevent the contagion from spreading. Most experts say achieving that needs 95 per cent of a population to be immune, whereas in Hackney the figure is 60 per cent, the lowest in the country. Dr Khan says the north of the borough, where the Charedi community is concentrated, is an “outlier” – figures are even lower. But he stresses that it would be wrong to lay the blame purely at the strictly Orthodox for failing to vaccinate. The picture is more complex. “The two main factors are deprivation and minority communities who may have barriers to accessing healthcare,” he says, explaining that he means all ethnic minorities in this very diverse borough. There have been outbreaks in Newham and Tower Hamlets in the past year, also both home to large, impoverished minority populations. Another factor is a strong strain of vaccine hesitancy among middle-class parents who favour alternative types of lifestyle and education. In the Stamford Hill street where I’ve lived for 35 years, all the mums I know say they’ve had their kids jabbed, though they know others who haven’t. If that’s true, it may be a reflection of class as this is prosperous part of the enclave. Dr Khan says it can be challenging to reach out to Charedi parents, because their health literacy is often quite low and “you do have to explain perhaps more than you would do to the general population around what viruses are, how immunity works”. He puts that down to the fact that people don’t have smartphones, and if their secondary education was strong on religion but short on science, they may never have learnt about vaccines at school. Edward Jenner and his cowpox experiments don’t feature strongly on the yeshivah syllabus. When explaining the low vaccine take-up, Dr Khan refers to the “Three Cs: low vaccine confidence, complacency and convenience”. Low vaccine confidence can be ascribed to the kind of doubt that has been stoked by online influencers, not to mention high-profile vaccine sceptics across the pond such as Robert F Kennedy Jr, the US Secretary for Health. I also sense that 15 years after rogue medic Andrew Wakefield was discredited, the spurious theories he propagated about links between MMR and autism still linger in people’s minds. Plus, we now have a generation of parents who simply don’t have a folk memory of measles as a terrible scourge. “People feel there are other competing priorities, particularly if they’ve got lots of children,” says Dr Khan. “If you’ve got large families, actually, just logistically getting to a vaccination site may be difficult.” The solution started with a communications strategy that involved putting adverts up around the borough and in printed media, and then making it easier for people to get their children’s jabs, he says. “Before the outbreak we’ve been running weekly clinics for people to come in on a Sunday at one, sometimes two GP surgeries in the area. And then instead of having two or three nurses, we’ve had up to seven or eight. We’ve also run community clinics at various sites on Thursdays.” And if people can’t come to the clinic, it comes to them at home. “Where there were a few children to be vaccinated, our nurse would go out to someone’s house.” The team has also tried to tackle myths and fears about inoculation. “We’ve done a lot of community engagement, we talk with rabbis and local community leaders and organisations about what the some of the prevailing myths may be.” Not everybody will be convinced immediately, he says. “It’s like advertising, you plant a seed one day, and then they see an advert. The next time, or the third time, they may well choose to have that child vaccinated. So, it’s about trying to work out who’s in front of you.” After a peak in July, measles figures are falling. Though it is still too early to say whether vaccination rates are rising, the doctor is sanguine. “I am an optimist. There have been some positive changes. We are engaging with the community as best we can. “We just need to find those allies and build a coalition of people that can help us. I think it may take long time to change mindsets, but any vaccine given to a child who wasn’t previously vaccinated is a win.”