Anyone ‘convicted’ of political offences would now be treated as

ordinary criminal prisoners; they would have to wear a uniform and do

prison work.

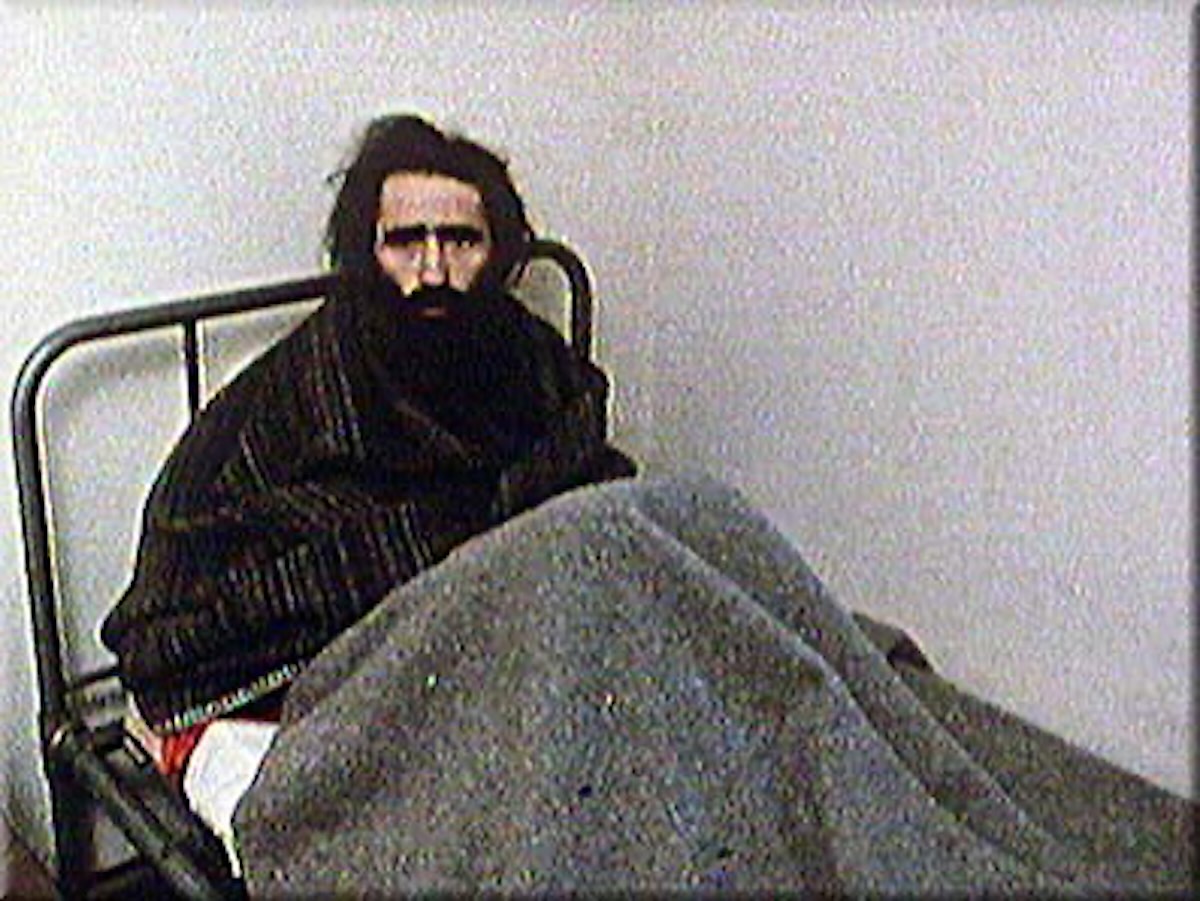

Kieran Nugent from Belfast arrived in the newly constructed H-blocks in

September 1976 and was handed a prison uniform by the screws, to which

he replied, “You will have to nail it to my back”.

Instead of the uniform, he took a blanket into his cell, and the Blanket

protest for political status was born. By Christmas, Kieran was joined

by over forty Republican prisoners on the Blanket protest and over time,

many other Republican prisoners joined the protest.

For refusing to wear prison uniforms, the prison authorities responded

by cancelling visits, cancelling yard exercises, and imposing a 24-hour

Seamus Kearney was arrested during an IRA operation in Finaghy Road

North and was imprisoned in January 1977. He was placed on remand in

Crumlin Road Gaol.

He related his experience in an interview with Micheal Jackson of the

Andersonstown News.

His imprisonment coincided with the building of the H-Blocks. At that

time, however, Seamus said, “Nobody knew what way the jails were going.”

Indeed, during an early encounter with Kieran Doherty, who would die on

hunger strike in 1981, he was informed that his comrades were

“disappearing off the face of the earth” after sentence.

After his own sentencing, Seamus was moved from the Crumlin Road to

H-Block 1 in June 1977. It was there that he first met future hunger

strikers Kevin Lynch, Thomas McElwee and the then block OC, Bobby Sands.

During their short time in H1, which was then used as a transitional

block, Seamus and his comrades resolved to join the blanket protest.

Non-conformity meant being locked in a cell for 24 hours a day and a

‘Number 1’ starvation diet.

“After refusing a uniform you were told to strip ‘everything’,” he said.

“It was all men looking at you, so it was a bit weird. They put the

clothes into a brown bag and I remember thinking to myself ‘I’m going to

get them back.’

“It seemed quite daunting because I thought I was getting some R and R,”

“We ended up in H5 and took each day as it came. One day led to another.

Your legs start getting tingly from the lack of exercise, but the idea

was to keep walking to keep moving.

“After a few months, we were lucky, because at the end of January 1978

Brendan Hughes, ‘The Dark’, arrived. I ended up in cell next to him.

Bobby ended up at the far wing of H5. Getting Brendan Hughes was

amazing. He was already a hero, even then.”

According to Seamus, the arrival of Brendan Hughes, who took up command

in the blocks, was pivotal in the escalation of the prison protests. The

blanket men were isolated from the outside world and the British

government was “winning the propaganda war”, but with the men voting in

favour of Brendan Hughes’ idea of no-wash protest in February 1978, the

protest began gaining public attention.

“We needed to recalibrate,” Seamus said.

“It was then that we were told that this was not a local jail dispute.

This was a part of governmental policy and that it was bigger than we

thought. I think the Brits thought we weren’t of the same calibre of

Connolly or Pearse – that we would do what we were told. But they were

wrong. They were hitting a raw nerve and they didn’t realise it, and

maybe we didn’t. We weren’t thinking about what it all meant, but our

backs were against the wall.”

Seamus continued: “It was about attracting national international

interest. We had to open new lines of communication to the outside world

and get our story out there, because at that time they were winning the

propaganda war.

“We were already getting harassed on the way out of our cells, so The

Dark said we were going to exploit that going into the no-wash protest.

The screws were already beating some of the lads. You were going out one

cell at a time and it was one man being hit by about 12 screws.”

Seamus was soon moved to H5 where he lost Brendan Hughes’ counsel, but

said he and his comrades were emboldened at the onset of the no-wash

protest. Their ingenuity in sending communications within the blocks and

to the outside world is now legendary. It was during that time, amid

increasing brutality from the screws, that the prisoners took the

decision to smear excrement on walls – a decision that Seamus said was

taken reluctantly.

“We didn’t know how we would even do it – the mechanics of it,” he said.

“We were improvising again. Some bright spark, Tom Martin, had the idea

of taking a piece of the mattress and using it as a sponge. That seemed

to be the only way to do it. Eventually we did it together. We started

smearing it on the wall – it was horrible. After about two weeks the

screws went ballistic. I remember the screw opening the cell door and

saying ‘you dirty bastards – you fucking animals.’ I think that’s when

the real hatred started forming. We didn’t feel good about putting it up

anyway. We weren’t animals, but we felt that we had to do it to

highlight the case.”

Seamus recalls 1979 as bad year for the blanket men, particularly in ‘an

seachtain dona’ (the bad week) of April that year, when “people were

literally beaten off the blanket”. He said the remaining blanket men

were determined to “save the IRA from obliteration” and, often, it was

comedy that got them through. While you were getting beaten you were

still laughing,” he recalled.

Seamus tells with a smile of a visit from an old neighbour who cajoled

him into singing ‘Smoke Gets in Your Eyes’ by Bryan Ferry – a move that

brought applause from the visiting room and, later, a beating from the

screws. Needless to say, she never visited again.

While the torture endured by the blanket men was immense, Seamus faced

one of his toughest challenges when he received word that the IRA had

executed his brother, Michael Kearney, as an informer in July 1979. The

screws initially mocked his brother’s death, but later offered supposed

salvation and a chance to leave the blanket. Michael’s name would not be

cleared until 2003 when it was revealed that he had been killed at the

behest of IRA informant Freddie Scappaticci, codename Stakeknife.

However, Seamus remained undaunting in his commitment to the IRA during

his 10 years in prison.

“I gave him my blessing to join the IRA,” he said.

“I felt he betrayed me and he betrayed Ireland. I didn’t know what I was

going to do. Everything stood still.

“I was in the middle of no-man’s land. I was neither with the IRA or the

British and I felt shell-shocked. The first thing that went through my

mind was ‘What am I going to tell the lads?’

“It was the first time I realised the distinction between mind and body,

which you’ll not understand until it happens,” he added.

“My body was telling me I’d had enough – I was starving, I had lice, I

had dysentery – but my mind was saying, ‘Tell them (the screws) to fuck

“I told them I had lots of brothers. There were 300 of them, one of them

was dead, but I had Sean on the outside and I had brothers in the

“I told the lads that the only way they would take me out is if they

carried me out. They weren’t going to break the back of the IRA.”

The H-Blocks saw a hunger strike in 1980 that saw the British government

renege on a deal it had struck with the prisoners. Tragically, 10 men –

Bobby Sands, Francis Hughes, Raymond McCreesh, Patsy O’Hara, Joe

McDonnell, Martin Hurson, Kevin Lynch, Kieran Doherty, Thomas McElwee

and Michael Devine – died on hunger strike the following year. Of the 10

that died, Seamus knew six of them personally, and he vividly recalls

the last time he saw Bobby Sands during Mass in February 1981.

“At the end of the Mass Bobby went round the lads clockwise,” he said.

“He came to me and smiled and said ‘I see you’re still here,’ and I knew

it was in relation to our Michael. I said ‘There’s nowhere else to go,

Bobby.’ He looked straight into my eyes and said ‘Good man – goodbye.’

“I had doubted him. Most of our wing had doubted him. To me he was just

like a Rod Stewart lookalike. I had given him the words to ‘This Old

Heart of Mine’ before – he liked that song. When I looked into his eyes

that Sunday they were like a shark’s eyes. He had resigned himself and I

knew he was going to go through with.

“The hunger strike was a formality. Bobby didn’t really die on May the

5th – he died in February. One after another they died and it was like

losing a part of yourself. It was the same reaction I had to losing our

Michael. It was like losing brothers. It was so catastrophic – and it

“Maybe it’s a physiological thing that I don’t understand, but when I

talk about it I can still feel that emotion as if it was yesterday and I

still struggle to get over it. I know I speak for a lot of the lads who

can’t have this conversation, but something broke inside me.”

Those who knew the men who died most keenly feel the sadness of 1981.

For Seamus, the death of his friend Thomas McElwee, who he knew from H4,

was most difficult of all, and one that he finds most painful to speak

about. He talks about his friend fondly, and will no doubt do so as he

tells his own chapter in the dramatic account of the blanket men.

“You are trying to bring people into that world and a lot of the lads

can’t talk about it – most of them don’t,” he said.

“For me, you don’t just talk about the protest, you actually relive it.

Once you open that Pandora’s box you don’t know what you’re letting out,

so a lot of the lads keep it closed.

“Today, with the rise of Sinn Féin, the republican movement is healthy.

It is a direct result of the fight against criminalisation. We thought

it would be a footnote in Irish history, but it became a pivotal moment.

Of the ten men who died on hunger strike I knew six of them personally.

It was such an intimate death for all of them that it’s difficult to

talk about.”