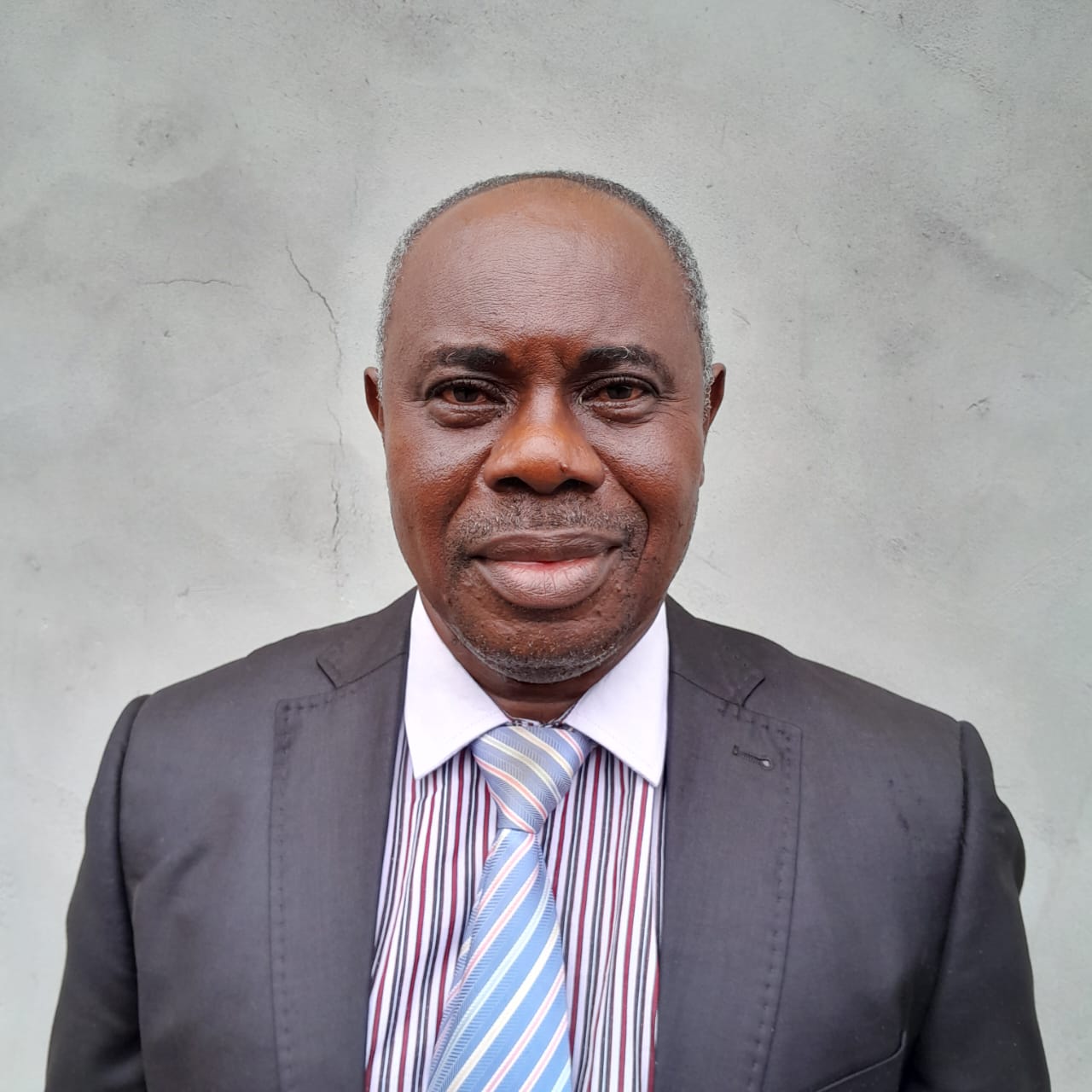

By Isaac Asabor

Copyright independent

In this hard-hitting interview, Prof. Godfrey Omojefe, President of the Chartered Institute of Financial and Investment Analysts of Nigeria, dissects Nigeria’s Sugar-Sweetened Beverage (SSB) tax. He argues that the policy, introduced as a health measure, has instead become a blunt revenue tool crippling industry, eroding jobs, and delivering negligible public health benefits. With government now considering a hike from ₦30 to ₦130 per litre, Omojefe warns that Nigeria risks sabotaging one of its most vibrant sectors through incoherent, short-sighted policymaking.

Professor Omojefe, the Sugar-Sweetened Beverage (SSB) tax was introduced in 2022 as a fiscal-health intervention. Three years down the line, what is your assessment of its impact?

The tax has failed on both counts. It was sold to Nigerians as a clever tool to raise revenue and tackle non-communicable diseases (NCDs). But in practice, it has neither improved public health nor stabilized industry. Instead, it has de-industrialised Nigeria’s beverage value chain, shrunk jobs, and undermined the very economic diversification the government claims to pursue. What is even more worrying is that none of the revenue collected has been transparently ring-fenced for health.

Can you give us a sense of the revenue generated and how it has been utilised?

Estimates vary widely, but Nigeria is believed to be raising between ₦27 billion and ₦200 billion annually from the SSB tax. The Centre for the Study of the Economies of Africa even projects that if the tax rises to ₦130 per litre, government could rake in as much as ₦729 billion yearly. But here’s the problem: despite all the lofty rhetoric about public health, not a kobo of this revenue has been transparently earmarked for hospitals, nutrition programmes, or NCD prevention. The budget allocations to health between 2023 and 2025—₦1.179 trillion, ₦1.336 trillion, and ₦2.48 trillion respectively, show no clear link to SSB revenue. This makes the tax nothing more than a blunt revenue-grabbing tool.

Beyond revenue, how has the tax affected industry?

The industrial toll has been severe. According to the National Sugar Development Council, sugar consumption in Nigeria fell by 16% in 2023, while domestic sugar production collapsed by 35%. Beverage manufacturers are reporting lower turnover, thinner margins, and job losses. Every litre taxed out of affordability reduces demand for farmers, refiners, transporters, and distributors. Essentially, we are not just taxing soft drinks, we are taxing the livelihoods of thousands across the value chain. This is deindustrialisation in real time.

Some critics say this looks like a policy contradiction, especially given the Nigerian Sugar Master Plan (NSMP). Do you agree?

Absolutely. On one hand, government is spending billions to subsidise and expand sugar production through the NSMP. On the other hand, it is strangling demand with punitive excise taxes. This is fiscal schizophrenia. Investors see this incoherence and draw the conclusion that Nigeria is an unpredictable place for long-term capital.

Supporters of the tax, such as CAPPA, argue that it helps fight NCDs. What’s your response?

That argument doesn’t hold water. Nigeria’s per capita sugary drink consumption is among the lowest globally, far below countries like Mexico or the UK where such taxes originated. Our NCD burden is not driven primarily by sugary drinks; it is caused by poor dietary diversity, low physical activity, weak health infrastructure, and genetic predisposition. Diabetes and hypertension peak in Nigerians over 40, but sugary drinks are mostly consumed by youth aged 15–20. So, the tax is not even targeting the right demographic. At best, it’s cosmetic; at worst, it punishes the wrong people while doing little for public health.

Now, there are proposals to raise the tax from ₦30 to ₦130 per litre. What does this portend?

If that happens, manufacturers will bleed further, consumers will turn to informal and unregulated substitutes, and the black market will thrive. The ₦729 billion revenue projection will remain theoretical, while real jobs, factories, and industrial confidence collapse. It is fiscal laziness disguised as health advocacy.

If you were to recommend an alternative, what would it be?

A tiered, sugar-content-based tax would have been far more effective. It would nudge manufacturers to reduce sugar levels without collapsing the industry. In addition, transparent earmarking of revenues could build public trust, with funds directed to school nutrition, fitness programmes, and health education. That way, both health and industry could benefit.

Finally, what is your overall message to government?

Nigeria is at a crossroads. We must align fiscal, industrial, and health policies in a coherent way. If government insists on pushing this tax to ₦130 per litre without reform, it will be remembered not as a champion of public health, but as the author of one of Nigeria’s most short-sighted industrial mistakes.instead become a blunt revenue tool crippling industry, eroding jobs, and delivering negligible public health benefits. With government now considering a hike from ₦30 to ₦130 per litre, Omojefe warns that Nigeria risks sabotaging one of its most vibrant sectors through incoherent, short-sighted policymaking.