By Fanny Chao,Hong-Lun Tiunn

Copyright thediplomat

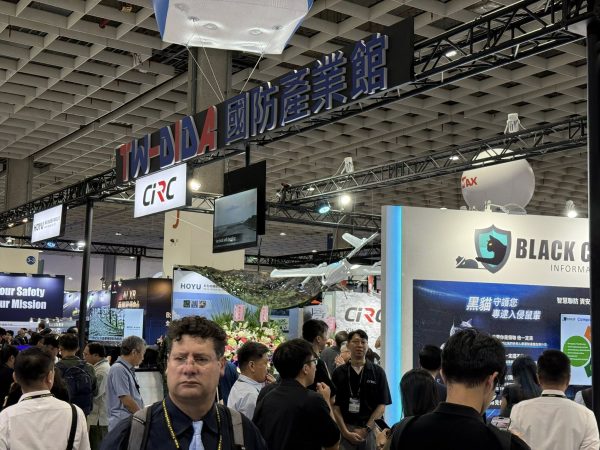

With uncrewed aircraft systems (UAS) becoming critical to modern warfare, Taiwan-U.S. cooperation on building a joint supply chain has made notable progress through U.S. UAS sales, subsystem partnerships, and business matchmaking. The progress was showcased in the Taipei Aerospace & Defense Technology Exhibition in September, which brought together 400 companies from 15 countries, most in the uncrewed system sector. During the event, the National Chung-Shan Institute of Science and Technology (NCSIST), a Taiwanese government-affiliated institute, announced its first cooperation with several American companies, including the co-production of loitering munition with Anduril, the Mighty Hornet IV high-speed attack UAV with Kratos, and the JUMP 20 series of UAVs with AeroVironment. Simultaneously, Taiwanese UAS exports to the United States have reached a peak. According to official data, Taiwan exported 5,017 UAS to the U.S. in 2025 up to July, which is almost six times the number exported in the whole 2024. What’s more, Taiwanese UAS company Thunder Tiger recently announced that its UAS was added to the U.S. Department of Defense’s Blue UAS Cleared List, making it the very first Taiwan company on the list. Despite the rapid progress, Taiwan is still struggling to achieve its goal of self-reliant UAS production. While Ukraine produces 4 million UAS annually, the Taiwanese Ministry of National Defense set a much smaller goal of 50,000 UAS before 2027. Because Taiwan prohibits the use of low-cost Chinese components, production costs are higher, making it difficult to compete in international markets and limiting overall capacity growth. Taiwan’s limited production capacity, the early stage of joint R&D, and the absence of Taiwanese UAS in U.S. supply chains still hinder cooperation. Recent Trump administration and Department of Defense (DoD) policies advancing allied cooperation while prioritizing “America First” manufacturing create both opportunities and challenges, while U.S. congressional initiatives point to deeper cooperation – provided they are institutionalized within a lasting framework. A Progressing Taiwan-U.S. UAS Alliance With Limits The recent expansion of Taiwan-U.S. cooperation is substantial, ranging from exports to procurement and technological collaboration. According to the Research Institute for Democracy, Society, and Emerging Technology (DSET), which utilizes official export data, Taiwan’s exports to the U.S. rose from just 278 units in 2023 to 874 units in 2024, and then surged to 5,017 units in 2025. By the second quarter of 2025, the United States had become one of Taiwan’s top three export destinations for UAS, after Poland and Czechia. Until September 2025, no Taiwanese company had been included on DoD’s Blue UAS list or secured U.S. federal procurement contracts; sales were limited to state and local government agencies for policing and public security. That changed when Thunder Tiger became the first Taiwanese firm added to the Blue List, paving the way for potential federal purchases. On the technology collaboration side, according to DSET’s research, progress in joint production remained limited before mid-2025. Taiwan had continued to acquire advanced systems through Foreign Military Sales, but its role had largely been confined to adaptation and sustainment. Unlike Japan or South Korea, Taiwan lacks a framework for co-production, assembly, or joint development with the United States. This began to shift, with the inclusion of provisions in the draft of the Fiscal Year 2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) that explicitly supported Taiwan-U.S. co-production. Senator Roger Wicker’s August visit to Taipei further signaled this policy direction. Last month, Taiwan announced multiple joint co-development and co-production initiatives with U.S. companies. At the business-to-business level, Taiwanese companies are also working directly with U.S. partners. Thunder Tiger has partnered with Auterion on the Overkill loitering munition, while Aerospace Industrial Development Corporation (AIDC) is collaborating with Maxar Intelligence to enhance UAV positioning and mapping. Vice President Chien Ting-hua of NCSIST stated that after Anduril’s on-site assessment, the company concluded that “establishing a low-cost, domestically based autonomous loitering-munition supply chain in Taiwan would take only 18 months.” The system is Anduril’s Barracuda, a Group 3 loitering munition, underscoring Taiwan’s potential in higher-end UAS production. AIDC, which leads the Taiwan Excellence Drone International Business Opportunities Alliance, is pursuing certification by linking directly with U.S. bodies and building a domestic mechanism. Acting Chairman Tsao Chin-ping stressed that with “non-red supply chain” compliance checks, “Taiwanese companies will become qualified suppliers for the U.S., opening up unlimited possibilities.” Yet, to meet Taiwan’s production goals for UAS, the current pace of progress must be accelerated. While recent U.S. policy signals create opportunities, they also pose challenges. Trump’s Executive Order 14307 in June, followed by a DoD implementation memo and a Department of Commerce’s Section 232 investigation into UAS imports, aims not only to exclude Chinese components from UAS supply chains but also to place greater emphasis on “America First” procurement. For Taiwan-U.S. UAS cooperation to deepen, both governments and industry must navigate the uncertainties these new policies bring. New “America First” UAS Policy and Allied Cooperation During the Biden administration, U.S. policy emphasized restricting adversarial UAS suppliers from U.S. procurement while gradually promoting allied cooperation in production. The Trump administration shifted priority to expanding domestic UAS capacity, though allied cooperation advanced in parallel. For foreign suppliers, the mixed signals in policy bring both new opportunities and new challenges. The restrictive trend began in 2019, during Trump’s first term, with the FY2020 NDAA, Section 848, which prohibited DoD procurement of UAS and components manufactured in China. The Biden administration reinforced the effort next year with 2021 DoD guidance clarifying definitions of critical components and procurement standards. Further restrictions expanded through subsequent legislation: Section 817 of the FY2023 NDAA added Russia, Iran, and North Korea to the list of prohibited supplier countries and extended regulation coverage from DoD to contracted services. The 2023 American Security Drone Act broadened the ban to all federal agencies, creating a comprehensive barrier against adversarial suppliers. As the embodiment of this series of restrictive policies, the Blue UAS List, a cleared procurement list managed by the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU), was established in 2020 and evolved into a mechanism for excluding adversarial suppliers. Trump’s return to office introduced a stronger “America First” acquisition strategy. His executive order 14307 explicitly prioritized U.S.-manufactured UAS over foreign-made systems, aiming to build a strong and secure domestic UAS sector. The order also called for accelerating UAS integration into the National Airspace System, advancing domestic commercialization through industry-led innovation and regulatory streamlining, and strengthening the domestic industrial base while promoting exports. Following the order, the DoD issued an implementation memorandum outlining key changes. Biden-era guidelines deemed burdensome were rescinded. The Blue UAS List was restructured by expanding certification authority to frontline units and other empowered agencies, accelerating approval timelines, and transferring its management to the Defense Contract Management Agency, which has greater administrative capacity. To expand small UAS (sUAS) adoption, rules were introduced to improve interoperability, speed delivery, and enhance flexibility. sUAS were reclassified as consumables to encourage rapid adoption, while limited adversarial procurement remained permissible for narrowly defined missions. In parallel, the Commerce Department initiated a Section 232 investigation into UAS and component imports, assessing national security risks that could lead to tariffs or other trade measures targeting foreign suppliers. Despite Trump’s domestic focus, allied cooperation developed late in the Biden administration has not been sidelined. Under Biden, Section 162 in the FY2025 NDAA directed the DoD to strengthen sUAS supply-chain resilience by leveraging domestic, allied, and partner sources. Complementing this, the DoD launched Partnership for Indo-Pacific Industrial Resilience (PIPIR) in 2024 to strengthen industrial resilience, expand capacity, and accelerate deliveries. The initiative includes 14 partner nations in the region, including Taiwan. The Trump administration has carried allied cooperation forward. Soon after his inauguration, the DIU announced a significant update to the Blue UAS List, adding allied suppliers such as companies from Switzerland, France, and Norway. At the 2025 Shangri-La Dialogue, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth highlighted PIPIR as a key pillar of regional deterrence, announcing UAS industrial collaboration as one of its first projects. Later in the year, the DIU confirmed to reporters its plans to open an office in Taiwan, noting that UAS will certainly be a focus. The move signals continuity in allied cooperation under the Trump administration. Meanwhile, congressional support continues. Section 1237 of Senate Armed Services Committee’s markup of the FY2026 NDAA calls for the establishment of a joint program for the fielding, co-development, and co-production of uncrewed and counter-uncrewed systems with Taiwan, with annual reporting through 2029. As a continuation of this policy, the DIU is reported to be expanding allied procurement channels to deepen regional collaboration on UAS. Next Steps: The Critical Moment for Deterring China These developments bring both opportunities and challenges for Taiwan. On the positive side, the order directs expansion and more frequent updates of the Blue UAS list, clarifying the pathway for Taiwan to secure access. However, the same order prioritizes U.S.-made systems, raising the bar for foreign suppliers. U.S. legislative momentum could change this. Section 1237 of the Senate’s FY2026 NDAA markup calls for a joint Taiwan-U.S. program to field, co-develop, and co-produce uncrewed and counter-uncrewed systems. The U.S.-Taiwan Defense Innovation Partnership Act of 2025, introduced in the House by members of the Select Committee on the CCP, proposes a structured partnership to coordinate development of dual-use capabilities, including UAS. Neither measure has been enacted, but both signal plausible next steps. If advanced, they would create a pathway for Taiwan to move beyond adaptation and sustainment and take initial steps toward a role in the production cycle, including greater ability to support and maintain systems in a conflict. In practice, this shift would serve two goals: first, improving Taiwan’s ability to field and sustain key platforms under crisis; and second, reducing long-term sustainment burdens on the U.S. by pre-positioning production capacity inside the theater. Anchoring co-production in platforms already in Taiwan’s inventory would speed integration and strengthen deterrence. Three strategic messages stand out. First, Taiwan’s entry into U.S. government procurement through Blue UAS certification is the necessary starting point to serve strategic goals for both Taiwan and the U.S. Achieving this requires a non-red supply chain that can meet U.S. certification and regulatory standards. Second, moving beyond adaptation and sustainment will require co-production. The most feasible opportunities are in sUAS systems such as loitering munitions, where joint production would build lifecycle capacity and enable Taiwan to sustain platforms in conflict without relying entirely on external support. Third, legislative measures now under discussion in Washington, including Section 1237 of the Senate’s FY2026 NDAA markup and the proposed U.S.-Taiwan Defense Innovation Partnership Act, could provide initial frameworks for joint programs. Taken together, these steps will determine whether Taiwan’s UAS strengthen deterrence in the Indo-Pacific and share the sustainment burden with the United States, or remain limited to domestic use.