By Contributor,Martin Gutmann,Stock Montage

Copyright forbes

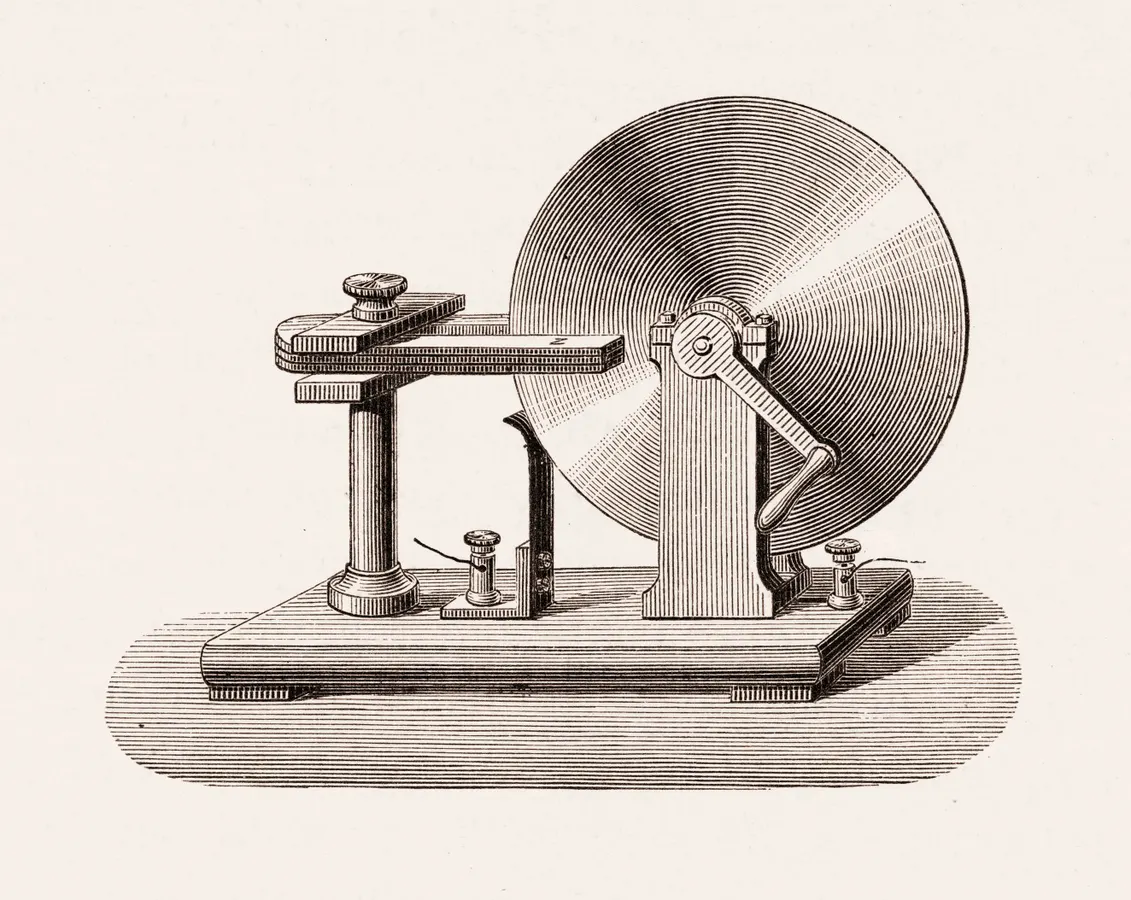

View of research laboratory apparatus similar to the type electric generator, sometimes called a Faraday disk (developed by British chemist and physicist Michael Faraday), mid 19th century. Electric current is generated when the metal disk situated between the u-shaped permanent magnet is rotated with the hand crank (Photo by Stock Montage/Getty Images)

Getty Images

In 1987, the Nobel laureate Robert Solow looked at a world awash in computers and spreadsheets—and shrugged. “You can see the computer age everywhere,” he quipped, “but in the productivity statistics.”

It was a strange paradox. Everyone agreed that computers were revolutionary. But on the ground, nothing seemed to be…revolutionizing. We had silicon chips. We had blinking screens. But the expected economic boom was nowhere to be found.

Solow’s quote became famous because it captured a familiar story: the overpromise of new technologies—and the long, often messy lag before their impact is truly felt.

And now, in 2025, we may be living through it again, this time with AI.

The Productivity Paradox, Rebooted

Generative AI tools are flooding workplaces. Companies are investing heavily. PowerPoint decks sparkle with the word “transformation” and “disrupt.” But once again, the productivity needle isn’t moving quite as expected.

“Despite billions in investment, measurable efficiency gains remain elusive,” writes Paul Hlivko, the Chief Innovation Officer at Blue Cross Blue Shield, in a Harvard Business Review article. How right he is. According to Boston Consulting Group research, 74% of companies were not generating value through their use of AI in 2024. More recent research from the MIT Media Lab is even more damning, concluding that a whopping 95% of companies generate no returns on their AI investment.

MORE FOR YOU

Which brings us to one of the most useful case studies from economic history: electricity.

Why Electricity Changed Everything…Very, Very Slowly

In the late 1800s, electricity was the shiny new thing. Edison was building power stations in Manhattan and London. Electric motors were available. You could install a dynamo in your factory and kiss your coal-scorched steam engine goodbye.

And yet? By 1900, less than 5% of mechanical power in American factories came from electrical motors. Steam power still ruled the industrial age. Why?

Because, as historians such as Thomas Nye, Paul David, and others have found, most factory owners swapped in new tech without changing old systems. They took out the steam engine and bolted in an electric motor—but left everything else intact: the layout, the belts, the central driveshaft, even the pace of production.

The old steam-powered factories had evolved around a single central drive shaft, which turned subsidiary shafts via a complex system of belts and pulleys. These belts drove every machine in the building—often across multiple floors—and ran continuously, even if only one station needed power. Factories were dark, dense, and dangerous, designed not around human workflow, but the mechanical limitations of steam.

Electricity changed all that—eventually. Because small electric motors were efficient, factories could distribute power locally to each machine, on demand. This made it possible to reorganize workspaces, space out machines, open windows, bring in light, and make operations both cleaner and safer. Even more radically, it gave workers more autonomy and flexibility in how they worked. But this required a complete rethinking—not just of power sources, but of workflows, management styles, and even factory architecture.

Few were ready. It wasn’t until the 1920s, nearly 40 years after the technology first appeared, that American manufacturing saw a dramatic surge in productivity.

What This Means For Managing AI

The same trap awaits us now.

Leaders who “plug in” AI—by automating workflows or generating content—without reimagining how their organizations actually work are likely to see underwhelming results. Particularly susceptible to such ineffective adoption, according to Nye, are “established firms,” who, “when a major innovation appears […] understand the technology, but remain committed to its [old] product and its production system.”

AI seems to be a new case in point. Its potential is not in replacing tasks one-for-one. It is, as a recent McKinsey & Company report argues, in changing the very architecture of decision-making, coordination, and leadership itself. And that requires more than a subscription to ChatGPT Enterprise.

For companies to see real value from their use of AI, they need to redesign how teams are structured, how value is created, and how human skills like judgment, empathy, and creativity are integrated with machine intelligence.

Just as electricity only transformed industry when factories were rebuilt around it, AI will only transform business when leaders rebuild the way work happens. Until then, we’ll keep adding electric motors to steam-powered systems—and wondering why the future feels stuck in the past.

Editorial StandardsReprints & Permissions