By Rabbi Dr Raphael Zarum

Copyright thejc

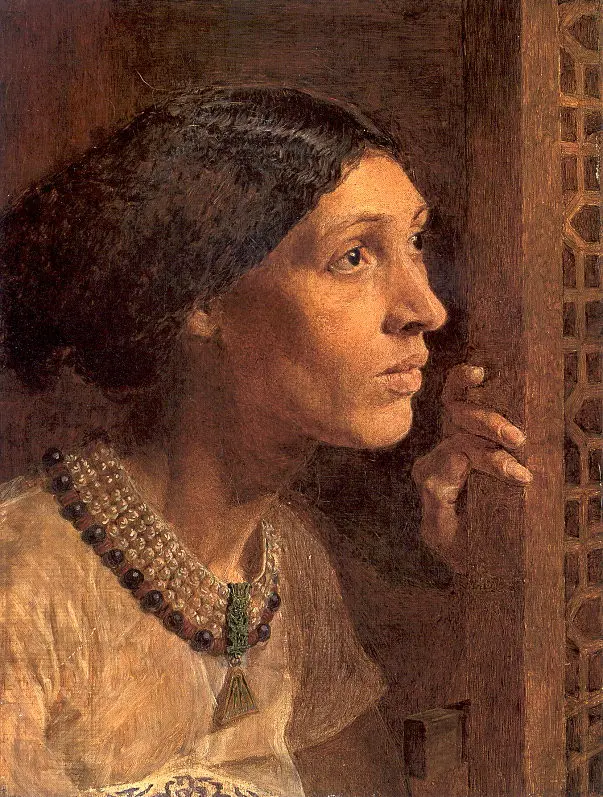

The shofar is hardly a versatile instrument, but that singular sound projects a power we all recognise on Rosh Hashanah. There is often some apprehension just before the appointed blower begins. Frozen in a moment of pregnant silence, the community stands motionless, waiting for the first note to ring out around the synagogue. It is one of a hundred that will be heard during the service. What do all these notes signify? We need to get the vibe of these vibrations. The sounding of the shofar is made up of musical phrases of three or four notes at a time. The first and last is always the tekiah, a sustained sound that frames the phrase. It serves to announce and conclude what comes in the middle, which is the focus. Bookended by the tekiah, this centrepiece comes in three forms: it is either the shevarim, three medium blasts; the teruah, nine staccato sounds; or the shevarim-teruah, combining the two notes. The crowd-pleasing end of the hundred-note medley is signalled by the tekiah gedolah, a much-extended tekiah. Although tekiah, shevarim and teruah are the well-known trio of shofar notes, only one of them actually appears in the Torah. Rosh Hashanah is identified as “a commemoration of teruah” (Leviticus 23:24) and “a day of teruah” (Numbers 29:1). There is no mention of shevarim at all, and tekiah only occurs in the verb form litkoah, “to blow”, as in “when you blow a teruah” (Numbers 10:5,6). But what exactly is a teruah? Onkelos, the second-century translator of the Torah into Aramaic, translates teruah as yevava, which is a cry of wailing, moaning or sobbing. The word is onomatopoeic: ye-va-va literally sounds like a series of sad cries. Significantly, this word occurs once in the Bible: “the mother of Sisera cried” (Judges 5:28). And so, to decide what kind of sounds should be blown by the shofar on Rosh Hashanah, the talmudic sages discussed the exact form of this cry. One thought it was the sound of moaning while another thought it was more of a staccato sobbing. This then is the origin of the three-blast shevarim and the nine-blast teruah, they are two interpretations of what emotional crying sounds like. To fulfil the Torah’s prescription for Rosh Hashanah, musical phrases with each kind of cry are blown. That is why there is a tekiah/shevarim/tekiah as well as a tekiah/teruah/tekiah. And there is also a tekiah/shevarim-teruah/tekiah to ensure we include the possibility that yevava is moaning and sobbing together. You might now be wondering why we don’t then have a version with the sounds reversed too, ie tekiah/ teruah-shevarim/tekiah. The Talmud answers that question: “generally, when tragedy happens to someone, first they moan and then they sob” (Rosh Hashanah 34a). The explanation makes it very clear that the whole function of the shofar is to recreate the sounds of Sisera’s mother. Understanding who this distraught woman was and why she was crying will teach us the essential purpose of the shofar on Rosh Hashanah. After Joshua’s conquest of the Land, maintaining control was not easy. According to the Book of Judges, each time the Israelites were attacked, a champion such as Ehud, Gideon or Samson arose to save them. When Jabin, a king from northern Canaan began to oppress the Israelites, Deborah the prophetess was their leader. She appointed Barak son of Avinoam to stave off the 900 iron chariots of Sisera, Jabin’s military general. Barak defeated Sisera and his army but Sisera himself fled on foot only to be killed by Jael the Kenite when he sought refuge in her tent. Powerfully portrayed in Gentileschi’s 17th-century painting, Jael hammered a tent peg through Sisera’s skull. After the victory, Deborah and Barak burst into song: “Hear, O kings… I will sing to the Lord, God of Israel… blessed above women is Jael, wife of Heber the Kenite… Peering through the window the mother of Sisera cried… [She said:] ‘Why is his chariot so long in coming? Why so late, the clank of his chariots?’ The wisest of her ladies reply – she even answers herself – ‘Why, they are dividing up the spoil they found!… colourful spoil for Sisera, colourful spoil of embroidery…’” (Judges 5:3,24,28-30). The general’s mother waits anxiously for her son to return from battle but is reassured that having bested the Israelites he was probably still busy picking out plundered haute couture to bring home for her! Sisera and his mother were enemies of Israel, but nonetheless her cries for him define the sound of the shofar. How can this be? Why should her moans and sobs determine what we hear on Rosh Hashanah? We have nothing good to learn from our foes, surely. Maybe, though, that’s the point. A mother’s cry for her child reaches beyond borders. It is the primal voice of the maternal bond. “Does a woman forget her baby, or not feel compassion for the child of her womb?” (Isaiah 49:15). This deepest of connections is what we evoke on Rosh Hashanah. We remind God of His love for us: “As a mother comforts her child, so will I (God) comfort you.” (66:13). The universal cry of the shofar calls the Creator to take care of His creations and “write us in the Book of Life”. It matters not that Sisera or his mother were wicked. A mother’s love is beyond reason, it is instinctual. Similarly, the sound of the shevarim and the teruah drives the Holy One to look beyond our mistakes and forgive us because we are God’s children. One suggestion as to the origin of the hundred notes that our blown is that Sisera’s mother cried out a hundred times for her son (Tosfot, Rosh Hashanah 33b), another is that a mother cries a hundred times when giving birth (Leviticus Rabbah 27:7). Both seek to express a mother’s unconditional love. The call of the shofar (photo: Getty Images)Getty Images There is a striking parallel to Sisera and his mother in modern literature. Roald Dahl’s antisemitism is well-known, but whatever we think of him, he was a master of the short story. In Genesis and Catastrophe: A True Story, he relates a conversation between a woman who has recently given birth and her doctor. The woman is distraught, asking repeatedly if her child is alright. The doctor tries to calm her, but she replies, “None of my other ones lived, doctor.” It turns out this is her fourth try and we hear the sad tale of the previous infant deaths. The woman is petrified her baby boy will not survive. The doctor reassures her, “He is small, perhaps. But small ones are often a lot tougher than the big ones. Just imagine, Frau Hitler, this time next year he will be almost learning to walk. Isn’t that a lovely thought?” Yes, she is Klara, Adolf Hitler’s mother, and this is a dramatisation of his birth. Dahl cunningly makes you care deeply for the mother and her son before gut-punching you with his identity. Even after the reveal, he continues to make us care for this woman. She too cries a yevava: “The mother was weeping now. Great sobs were shaking her body.” Should we have empathy for this woman even when we know what her son will become? This is Dahl’s challenge to the reader. In turn, this is reminiscent of the very first cry in the Torah. When the water had run out, Hagar could not bear to watch her son die, so she sat apart from Ishmael, and wept desperately. According to Rashi, the angels pleaded with God not to save Ishmael, knowing that his descendants would persecute Israel, but in response, “God heeded the voice of the boy, there, as he was.” (Genesis 21:17). We have come full circle, for it is this story we read on the first day of Rosh Hashanah. Listening to the notes of the shofar, we might reflect on two levels. First, on the countless times in Jewish history when mothers, and indeed fathers, have cried out to the Almighty to protect their children. Their love has carried us for centuries and reminds God of our unwavering loyalty. Second, the piercing sound of the ram’s horn forces us to recognise the basic humanity even of our adversaries, for we are all in God’s image. Rabbi Dr Zarum is dean of the London School of Jewish Studies (LSJS) where he holds the Rabbi Sacks Chair in Modern Jewish Thought Top image: The Mother of Sisera anxiously waits for her son (Joseph Albert Moore, 1861)