Copyright myjoyonline

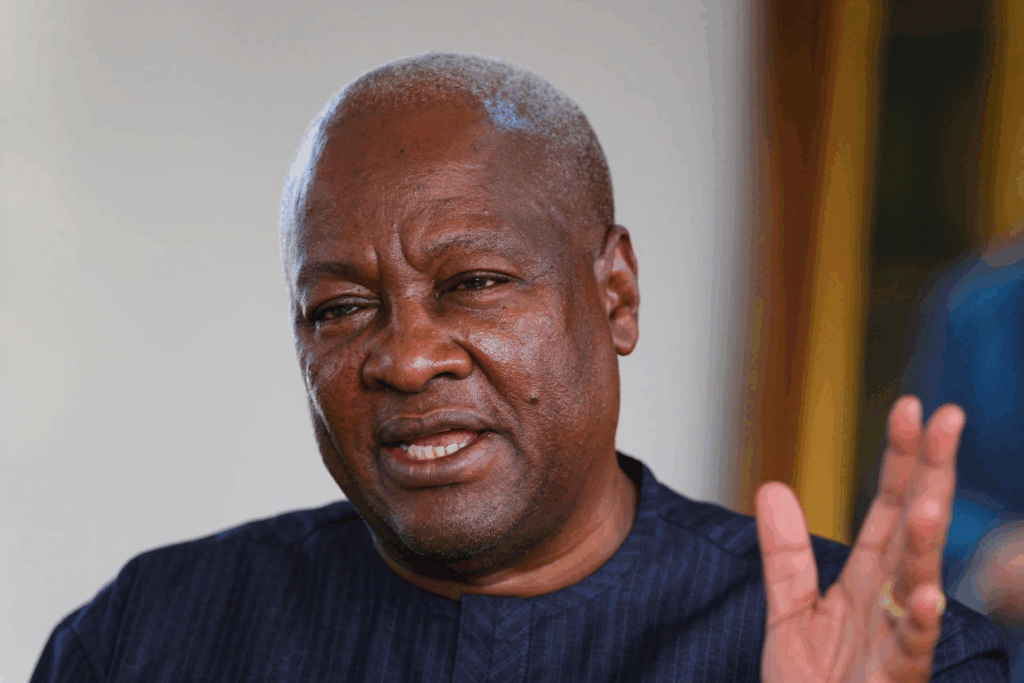

After the buoyant launch of the programme, it has no doubt sunk under the weight of reality. The only two things holding the programme up positively in the public mind now are the aura and goodwill of President Mahama and the credibility of Goosie Tanoh, whose expanding team at the 24-Hour Secretariat is gradually turning into bureaucrats. They are supposed to be a thought-to-action army. The most widely known criticism of the programme is that “you cannot introduce a night economy by government fiat; rather, it must be driven by economic and market forces… it must be organic.” This has been explained away with “words”, but the reality is that all government agencies which have launched 24-hour operations have done so because there is demand for services beyond normal working hours. To do otherwise would mean employing new staff with no real work for them. That might be politically expedient for the government but would constitute a complete waste of financial resources. Those who rushed to score political points — such as GIHOC — have come face to face with economic reality and are now abandoning night shifts. The private sector could provide key indicators for the success of the 24-Hour Economy. For years, enclaves in Tema, the Accra industrial area, and other parts of the country have operated around the clock, driven purely by market demand. In all these sectors — at least the fifty I surveyed — customer demand has been the basis for running three shifts a day. President Mahama has presented the 24-Hour Vision as the coherent anchor of his second term in office. Supported by the Big Push, the Mahama government has concluded the framework within which it wishes its second administration to be assessed by history. Is it a good strategy to affirm one’s entire manifesto and present it to an uncertain public? Well, sometimes no strategy is inherently good or bad until it has run its course. If he succeeds, it will be a great strategy; if not, it may be deemed too risky to have revealed his vision so early and in such concrete terms — a hopeless gamble, perhaps. Yet many great leaders have taken this path: present your vision early, in concrete terms, and let it guide your course. If he succeeds, Mahama would find himself up there with Nkrumah. His success could be measured on many fronts — one of them being the courage to say: “This is the economic and industrial plan I want my government to be remembered for.” In our political environment, leaders often present manifestos as election rituals, only to assume office and act as they wish, later hoping and praying for success. In this brief analysis, the Big Push and the Volta Basin Agro-Industrial Corridor have been left for another day. My focus here is to provide itemised points for the success of the 24-Hour Vision, which, in its current state, appears stalled. Understanding the 24-Hour Economy Vision The 24-Hour Economy proposes that many sectors of Ghana’s economy operate three eight-hour shifts. Public institutions with high customer traffic — such as ports and harbours, the Passport Office, Customs, and the DVLA — are singled out for early adoption, with incentives such as tax breaks, cheaper electricity (off-peak tariffs), improved infrastructure (power, security, lighting), and regulatory or legal reforms to enhance the business environment. The government’s stated objectives for the programme include: Creating jobs, especially for the youth, by adding shifts and extending operating hours. Boosting productivity and better utilising existing infrastructure. Increasing output and transforming Ghana into a more export-led, value-added economy rather than one dependent on raw materials. These aspirations are sound and difficult to refute. However, large-scale implementation remains the key challenge. There is currently no local data on the night economy to drive a nationwide rollout. As a private sector–driven initiative, funding remains a major concern. The Bank of Ghana, through its Governor, has promised to leverage its monetary policy tools to “control inflation, stimulate economic growth, and maintain price stability.” The Governor believes that “with stable inflation, the Central Bank can adjust interest rates downwards” to improve access to credit. These are encouraging statements to any politician with timelines hanging around his neck — but they raise serious questions: When will the BoG start leveraging these monetary policy tools? How long will it take for their effects to be felt in the real economy — six, twelve, or eighteen months? At what level must inflation stabilise to attract general funding for the programme? How many financial institutions have signed on to lend? How much have their boards committed to the programme in the short and long term? What are the qualification criteria? Will there be government guarantees? How affordable will the funds be? These questions are critical to the success of the vision. Given the nature of the programme and the lending culture in the country, it would be reckless to leave funding entirely to market forces. Implementation Framework The government has imposed an implementation plan on itself. While commendable, this is not an end in itself. The first step — moving beyond campaign slogans to formulating a policy strategy — has largely been achieved. The next is the 24-Hour Authority Bill, which will give legal backing to the pre-programme phase, followed by the rollout of the various arms of the vision. Commendable as these steps are, the thrust of the programme lies not in the public sector but in the private sector. A practical roadmap tailored to private participation will be the key determinant of success. The Way Forward Institutional Framework and Oversight:Establish a solid institutional backbone for governance, coordination, and accountability. This coalition should involve the Ghana Police, National Security, GIPC, GEPC, the Ministry of Finance, banking and insurance sector players, the GRA, and the Ministries of Energy, Interior, Transport, Employment, and Local Government.They should develop key performance indicators (KPIs) such as jobs created, energy reliability, crime reduction, SME participation rate, and GDP growth contribution. Leadership Structure:Appoint a 24-Hour Economy Commissioner, one step below Goosie Tanoh, to handle the management and operational aspects while Mr Tanoh focuses on policy and strategy. Infrastructure:Reliable infrastructure must be the foundation — ensuring uninterrupted power, transport, communication, and water supply. GRIDCo’s distribution systems must be reorganised to guarantee dedicated power to industries through: 24/7 grid stability and backup systems. Investment in solar and natural gas generation. Expansion of 24-hour transport services in major cities. Strengthening internet connectivity for e-commerce and logistics. Security and Public Safety:Establish Night-Time Policing Units, improve street lighting, and partner with private security firms to protect industrial zones. Labour and Workforce Readiness:Update labour laws to address night shift allowances, maximum hours, rest periods, and safety obligations. Provide welfare programmes such as subsidised transport, health screening, and safety training. Economic Incentives:Offer tax breaks, energy subsidies, and low-interest loans for firms adopting 24-hour operations. Designate 24-Hour Economic Zones (24EZs) as pilot industrial hubs with full infrastructure and security support. Phased Implementation:Roll out gradually — Phase 1 (Years 1–2): ports, manufacturing, logistics, healthcare, and hospitality in Accra, Kumasi, Takoradi, and Tamale.Phase 2 (Years 3–5): retail, banking, and education support.Phase 3 (Years 5+): full national integration. Energy Efficiency and Sustainability:Encourage solar rooftops, LED lighting, and off-peak electricity pricing. Incorporate the programme into Ghana’s Energy Transition Plan. Urban Planning and Mobility:Develop “Night-Economy Districts” with extended licences for markets and entertainment, enforce noise and waste controls, and improve late-night transport through partnerships with ride-hailing services. Cultural and Social Integration:Promote public acceptance through awareness campaigns, community engagement, and women’s safety measures. Depoliticise the initiative to make it a national — not partisan — agenda. Data, Innovation, and Monitoring:Build a National 24-Hour Economy Dashboard to track progress. Partner with universities and think tanks like ISSER and CEPA for research and impact assessments. Inclusivity and Equity:Extend credit and training to SMEs, artisans, and market traders. Improve night market facilities and ensure gender-sensitive policies. The success of Ghana’s 24-Hour Economy depends on coordinated implementation, reliable infrastructure, strong governance, and inclusivity. With clear incentives, sustainable energy, and robust worker protection, Ghana can lead West Africa in building a modern, resilient, and competitive 24-hour economy. There are no quick fixes. Realistically, the government needs close to seven years to fully integrate the 24-Hour Economy into the national framework. Patience and steady progress are essential. Now that the Vision has been codified, the government must take the programme out of the hands of politicians and entrust it to technocrats with realistic timelines. Rushing it for political expediency will compromise both its success rate and long-term sustainability. . Written by Arnold Boateng, Author / Consultant Email: arnoldboateng@gmail.com