By Rebecca Macfie

Copyright newsroom

The child is 14 and small for his age. His body language suggests he would rather be anywhere but here at Ngā Hau e Whā Marae in the suburb of Aranui, Ōtautahi Christchurch, on this bright autumn day.

Seven teenagers are scheduled to appear at today’s sitting of Te Kōti Rangatahi ki Ōtautahi – Christchurch’s Rangatahi Court. Some have whānau alongside them and some are accompanied only by their youth advocate, social worker or youth mentor. Most have been here before, but it is the small boy’s first time. His dad and young sisters are with him.

All of the rangatahi here today have been charged by police, have admitted their offending and have attended a family group conference under the Oranga Tamariki Act 1989 at which a plan was developed to hold them to account for the harm they have done to their victims and to create opportunities for support and healing. All are having their progress against that plan monitored through regular appearances at Te Kōti Rangatahi rather than in the main Youth Court.

The day began at 9am at the waharoa, the entrance of the marae. The manuhiri – including the teenagers, whānau, police, youth advocates, education outreach and forensic health workers, youth mentors and court registrar – mingle together awaiting the call of the kaikaranga to enter the marae ātea. I wait nervously among them: today is my first visit to a rangatahi court. Over the following months I will return nine times to Te Kōti at Ngā Hau e Whā, as well as making two visits to Te Kōti at Manurewa Marae and two to Hoani Waititi Marae in south and west Auckland.

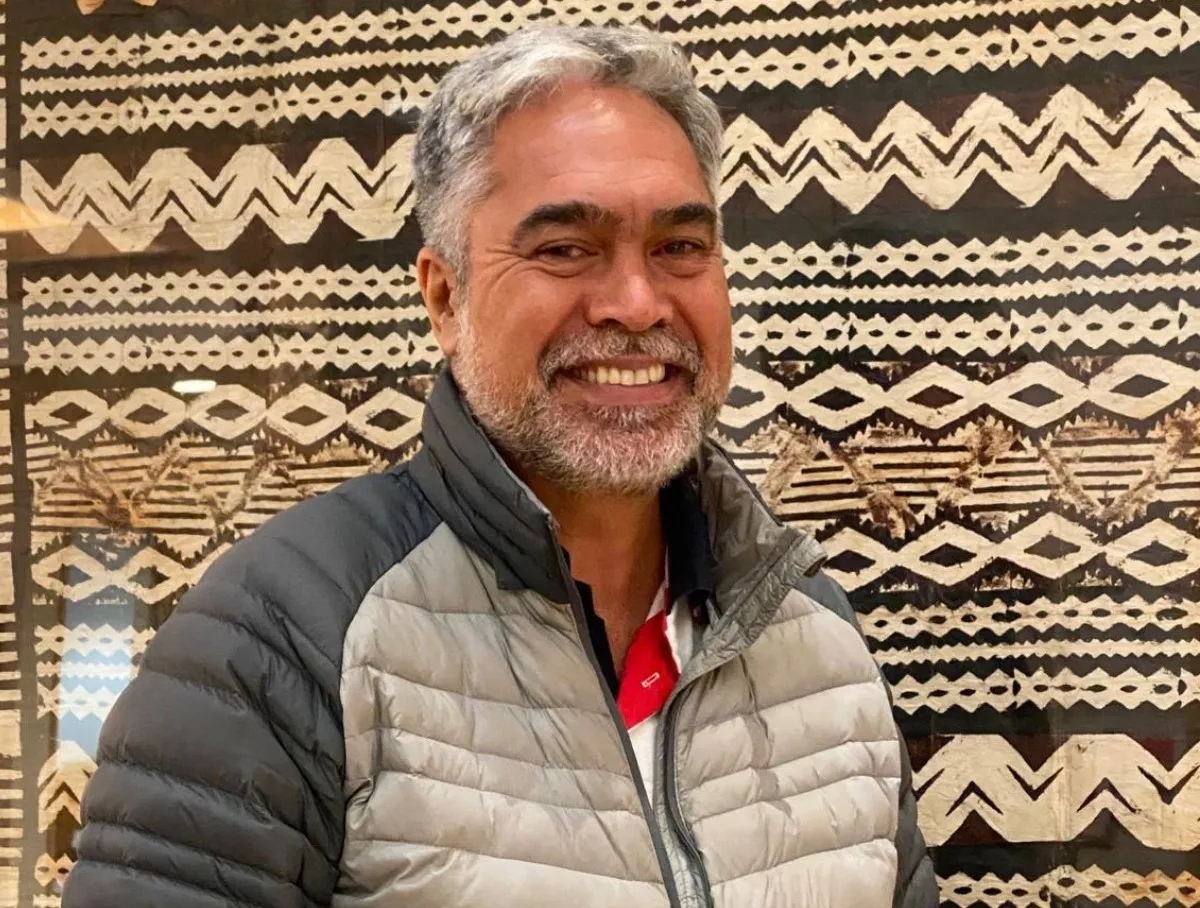

A worker from the Ministry of Education – a fluent te reo Māori speaker – gives a karanga in reply for the manuhiri, and we slowly approach Te Aritaua Pītama, the smaller of Ngā Hau e Whā’s two wharenui, named in honour of a prominent Ngāi Tahu kaumātua. Once we are inside, Judge Quentin Hix (Ngāi Tahu) stands to deliver the whaikōrero – first in te reo Māori and then in English. Judge Hix grew up in the South Canterbury town of Temuka and has strong links with Arowhenua Marae. One of the youth workers replies in te reo for the manuhiri. Waiata are sung, first by a kuia from the hau kāinga (people of the marae) and in reply by the manuhiri. All the visitors then move past the judge and kaumātua to mingle breath with hongi. Many also exchange a kiss and a warm hug.

Everyone pitches in to rearrange the chairs into a circle big enough for everyone to participate in whakawhanaungatanga, the process of establishing and expressing relationships with one another. It is expected that everyone will stand and deliver a pepeha telling who they are, where they are from and who they belong to.

Pepeha range from a few carefully memorised lines to the eloquent reo of kaumātua and other skilled speakers. Each person speaks for as long as they choose.

The new boy stands briefly and manages to say his name, so quietly it is barely heard. Everyone murmurs ‘kia ora’ in acknowledgement that, for him, this is an achievement. His dad stands next. He says he is sorry that he cannot speak te reo Māori, but that he is here to support his ‘young fella’.

Forty- five minutes later, the pōwhiri is almost complete. Everyone is united in the kaupapa – to support the children here who are in trouble with the law, ensure accountability for their offending, wrap them in support, help them understand who they are and where they are from and guide them away from the pipeline of youth offending to adult incarceration.

All that remains, before each young person is called for a kōrero with the judge, kaumātua and kuia, is a cup of tea and kai. The cheese scones baked by the ringawera (cooks) at Ngā Hau e Whā are renowned. They are still piping hot when we get to the wharekai. They are shared by the young people who have broken the law, by the police youth aid officers who are there to report on their adherence to bail conditions and any further offending, by the judge who holds the key to their future, by the support workers. The pōwhiri and whanaungatanga have collapsed the heirarchy into a shared kaupapa of care.

Back in the wharenui, the court is laid out as a horse shoe. The judge and kaumātua are at the head. Police, Oranga Tamariki (Ministry for Children) workers, educa-tion workers, forensic health workers and myself – the visiting journalist – are on either side. Inside the horse shoe are chairs for the young people, whānau and their support crew. Everyone sits at the same level. There are no security guards on the doors, no metal detectors or scanning machines.

First on the list is a girl who has admitted getting into stolen cars. Her mother and father are not here; her dad has sent his apologies. She is Ngā Puhi and Ngāi Tahu, but knows little of her heritage. With support from an Oranga Tamariki worker, she has managed to put together a few lines of her pepeha, and Judge Hix congratulates her. She is sixteen and not in school. She tells the judge that her days are spent looking after younger siblings.

Marae kaumātua Henare Edwards tells her that he shares her Ngā Puhi heritage, and asks her to do some-thing for him: could she do some more research on where she comes from, and come back next time and tell him about it? She says she will do that. “It’s lovely to see you today,” says Matua Henare. The girl manages a smile.

Next is a boy who attends with his mum, who has good progress to report. “He smashed out his community service in a week. He worked from 8.30 til 4. And they were praising him so much, his work ethic. I’m really proud of him.” He is going for his driver’s licence and wants to get into a pre- trade training course. He’s been doing kapa haka. All of these successes are acknowledged and encouraged by the judge and kaumātua.

The new boy is up next, with his whānau and a mentor from a local youth development NGO in support. His body is curled into his chair, and he has his head in his hands. He too has been caught in cars stolen by mates. Kaumātua Ross Paniora (Ngāti Porou, Ngāi Tahu), a fluent speaker of te reo Māori and a former high school teacher, tells him: “It’s a privilege to meet you today.” The family has been living in emergency accommodation and he has been out of school for a long time, but with the careful support of Ministry of Education worker Tracey Wairau (Tapuiki, Te Arawa), he has built up his attendance at an alternative education provider. His younger siblings have also been eased into school by Wairau, who has worked with Te Kōti Rangatahi for 10 years.

The boy is too anxious to speak, even when Judge Hix assures him that everyone in the room is here to support him. He shrugs when Matua Ross asks how he is doing and what he is interested in. The kaumātua gently enourages him to continue with his task of learning a little more of his whakapapa. A new date is set for his next appearance at Te Kōti Rangatahi.

The remaining teenagers are called one by one into the horse shoe, each greeted with a mihi from one of the kaumātua or the judge. They are asked about what’s been happening in their lives, about progress in getting their hours of community service completed, about letters of apology they’ve written to victims, about mentoring support and about reconnection with education or job training. Voices are soft, there is sometimes laughter and the tone is informal. The young people are spoken to by their preferred first names and asked about their interests and goals – although many have none. Their positive attributes and achievements are singled out for comment, and setbacks are noted as something to be learned from rather than as a mark of failure. At the end of each child’s appearance, they and their whānau and supporters are asked to hongi with everyone in the room.

Today, most leave with a new date to appear again for monitoring against their family group conference plan. But one leaves with the ultimate goal of everyone in the wharenui: a discharge under section 282 of the Oranga Tamariki Act. For those who complete their plan as agreed, a ‘282’ means they walk out the door with a clean slate – as a child who can still dare to dream of a decent future; whose impulsive and still- developing teenage brain can continue to mature without the stain of a criminal record. Hopefully, they walk away with a seed of pride planted in who they are as rangatahi growing up in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Taken with kind permission from Hardship and Hope: Stories of Resistance in the Fight Against Poverty in Aotearoa by Rebecca Macfie (BWB Texts, $20), available in bookstores nationwide. It will be launched at the Stout Research Centre for New Zealand Studies in Wellington tomorrow, September 11, at 6pm (doors open 5.30pm). The book expands on Macfie’s widely acclaimed series in the Listener, in her collection of stories about whanau and communities who refuse to accept a nation defined by deprivation and lost potential: “From papakainga in Te Hauke to schools in Papakura and marae in Otautahi, Macfie discovers powerful local responses to poverty that insist on hope as resistance.”