Copyright Slate

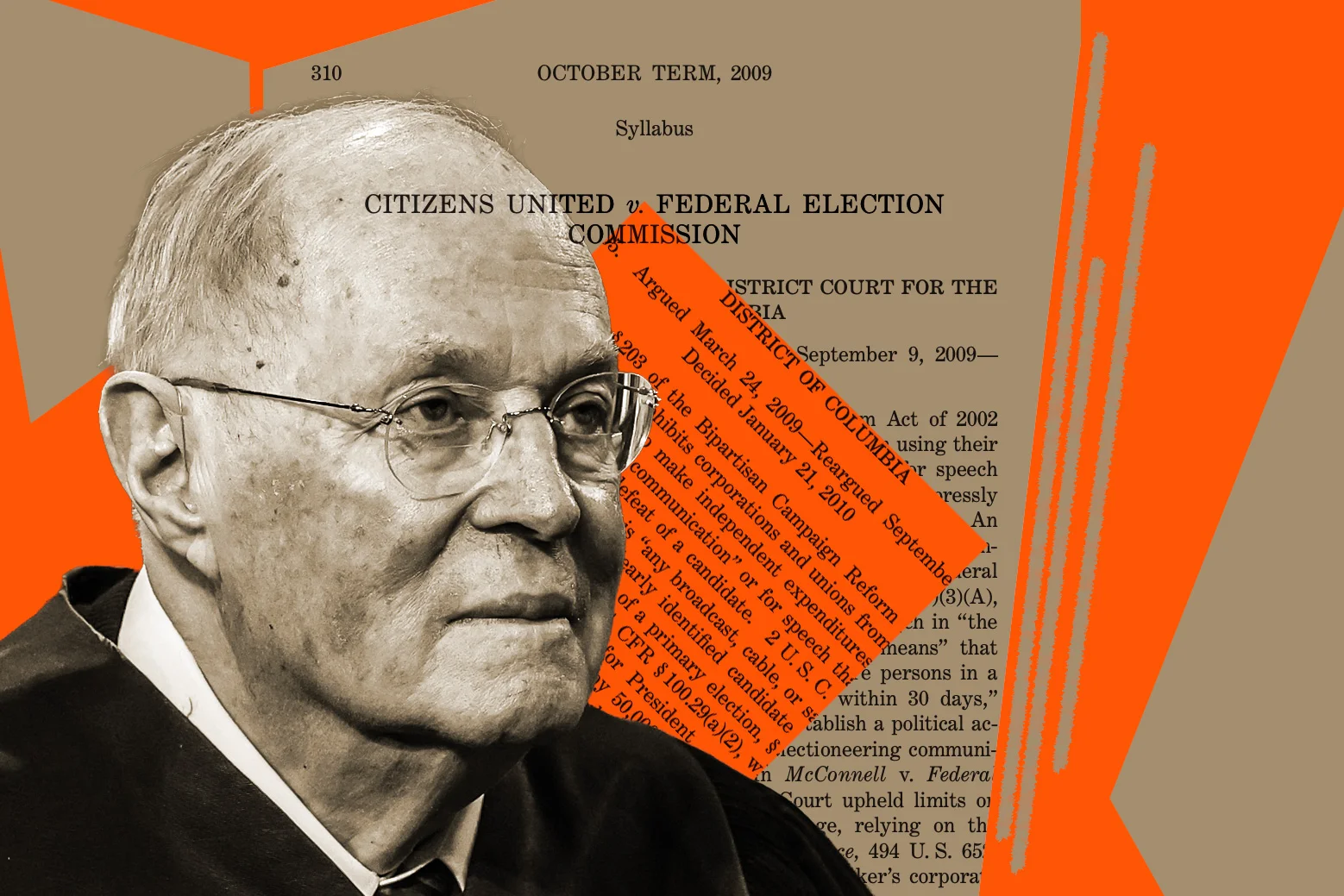

The following essay is adapted from Master Plan, a new book by David Sirota and Jared Jacang Maher based on their award-winning podcast. When the Supreme Court issued its 2010 ruling in Citizens United v. FEC, the floodgates opened for unlimited corporate and dark money to pour into American elections. Billionaires could now bankroll candidates anonymously. Super PACs flourished. And a once fringe concept—that money is speech, and corporations are people—became enshrined in constitutional law. As Justice Anthony Kennedy’s legacy is cemented with fawning profiles timed to his new memoir, Life, Law & Liberty, it’s worth recalling his role authoring the decision that devastated American democracy. Anthony Kennedy’s story begins in mid-20th-century Sacramento, California, a city that resembled the fictional Hill Valley from Back to the Future—bustling, idyllic, and full of white picket fences. But beneath its charm lay California’s version of a political swamp. As the state capital, Sacramento teemed with lobbyists, politicians, and a steady flow of money greasing deals over everything from water to redevelopment. Kennedy’s father was at the center of this world. A powerful lawyer and lobbyist, he ran a thriving business of influence-peddling focused on the state legislature. When Kennedy’s father died of a heart attack in 1963, 27-year-old Anthony took over the firm. In his early career as a lobbyist, Kennedy quickly earned a reputation for his skill in distributing campaign money to legislators on behalf of his clients. Among his contemporaries was Ed Meese, a recurring figure in the conservative movement and a close ally of a certain B-movie actor turned archconservative governor of California: Ronald Reagan. Gov. Reagan eventually recommended Kennedy to President Gerald Ford for a federal judgeship in 1975. At just 38 years old, Kennedy became the youngest federal appellate judge in the country. On the bench, Kennedy quickly developed a reputation for being mild-mannered, polite, and pragmatic. While undeniably conservative, he leaned toward a libertarian philosophy that emphasized individual freedoms and preferred narrow, case-by-case decisions over sweeping ideological rulings. By the late 1980s, he was recognized as a leader of a conservative minority on the more liberal 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. Then came 1987, when Justice Lewis Powell announced he was stepping down, setting off a political frenzy. His departure gave President Reagan the chance to nominate a new justice. After a pair of disastrous failed nominations, Reagan turned to a safe choice: his old Sacramento ally, Anthony Kennedy. Unlike Reagan’s other doomed picks, Robert Bork and Douglas H. Ginsburg, Kennedy’s nomination was controversy-free. He was widely seen as the “nice guy” alternative to Bork’s combative demeanor and Ginsburg’s youthful indiscretions. Even Kennedy’s past as a lobbyist in Sacramento didn’t raise red flags. This time, Senate Democrats offered no resistance. Kennedy was unanimously confirmed on Feb. 3, 1988. When Kennedy joined the Supreme Court, he began to carve out a moderate profile, particularly on social issues. In 1992, he co-authored the majority opinion in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which reaffirmed Roe v. Wade while allowing for certain abortion restrictions. The ruling cemented Kennedy’s image as a centrist willing to straddle ideological lines. But all the while, Kennedy was sending subtle signals to those working to implement the vision laid out in the infamous Powell Memo. In 1990, he dissented in Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce, a case that upheld a state law barring corporations from using treasury funds to support political campaigns. Kennedy argued against such restrictions, framing them as an infringement on free speech. He also voted to allow political parties to make unlimited expenditures on behalf of their congressional candidates, so long as they didn’t coordinate directly with those campaigns. Later, he dissented in the case that upheld provisions of the McCain-Feingold campaign finance law. For most of his first 17 years on the court, however, Kennedy kept a relatively low profile. But his quiet presence on the bench took on seismic importance when Sandra Day O’Connor and William Rehnquist were replaced by John Roberts and Samuel Alito. Suddenly, Anthony Kennedy found himself in a uniquely powerful position. With four liberal justices and four solid conservatives, Kennedy’s vote became the swing vote, capable of deciding the most contentious issues of the day. By the late 2000s, the media had fully embraced Kennedy’s role as the court’s kingmaker. News reports highlighted him as “the swing vote in a divided court,” as “a moderate conservative whose votes on high-stakes cases are close to impossible to predict,” and “the man in the middle, the right-leaning justice who often swings left on some of the most hot-button cases.” For many liberals, Kennedy’s rulings with liberal justices on LGBTQ+ issues, habeas corpus, and abortion rights seemed like a bulwark against the court swinging too far to the right. Conservative legal strategists like James Bopp Jr. knew better. The small-town lawyer from Terre Haute, Indiana, launched a legal blitz on the issue of campaign finance, filing dozens of lawsuits in state and federal courts. Some failed. But each case was a potential stepping stone, a way to test arguments, refine tactics, and nudge the judiciary closer to his vision of deregulated campaign spending. And his eyes never strayed from the ultimate prize: the Supreme Court. Bopp knew his cases wouldn’t matter unless they reached the right court at the right time. One justice in particular became the focus of Bopp’s attention: Anthony Kennedy. Crucially, Kennedy held strongly personal beliefs about the First Amendment, viewing it as a near-sacred pillar of individual freedom. As with any case before the Supreme Court, winning wasn’t just about knowing the law—it was about knowing your audience. Bopp recognized that if he could craft the right case, one that appealed to Kennedy’s First Amendment absolutism, there was a real chance to rewrite the rules of American democracy. For Bopp, this opportunity came in the form of a case that he described as “absolutely critical”: Federal Election Commission v. Wisconsin Right to Life. Heard by the Supreme Court just after John Roberts and Samuel Alito joined the bench, it presented the perfect moment for Bopp to test the inclinations of the new conservative majority—and Kennedy, the pivotal swing vote. In 2004, the anti-abortion group Wisconsin Right to Life had contacted Bopp with a dilemma. They wanted to pressure Wisconsin’s two Democratic senators not to filibuster judicial nominees during an upcoming confirmation vote. One of those senators, Russ Feingold—the coauthor of the McCain-Feingold campaign finance law—was particularly vulnerable, as he was up for reelection that year. To apply pressure, Wisconsin Right to Life began airing TV ads stating that “There are a lot of judicial nominees out there who can’t go to work,” and urging viewers to “Contact Senators Feingold and Kohl and tell them to oppose the filibuster.” These ads fell within the “blackout period” imposed by McCain-Feingold, which prohibited certain types of election-related advocacy within 60 days of a general election. Because the ads named Sen. Feingold, they were considered electioneering and thus subject to regulation under the law. Bopp filed a lawsuit arguing that these restrictions violated free speech. The case reached the Supreme Court, and on April 25, 2007, Bopp argued before a bench now including Roberts and Alito. The central issue was whether the Wisconsin Right to Life ads constituted legitimate “issue advocacy” or covert electioneering. Justice John Paul Stevens pressed Bopp on whether the ads were genuinely intended to influence Sen. Feingold’s stance on filibusters. Bopp confirmed that this was the case, explaining that the purpose of the ads was to lobby the senator ahead of the upcoming vote. Stevens, unconvinced, asked if such an effort was realistic. Bopp insisted it was. “Grassroots lobbying can change minds,” he said. At this point, Anthony Kennedy interjected: “Is that called democracy?” “We are hopeful, Your Honor,” Bopp responded. With Kennedy as the key swing vote, the court’s conservative majority ultimately sided with Bopp. The narrow ruling held that Wisconsin Right to Life’s ads did not constitute “express political advocacy” because they didn’t explicitly tell viewers to vote for or against a candidate. This decision exempted the ads from McCain-Feingold’s restrictions. In plain terms, the Roberts court had overturned a significant portion of McCain-Feingold just four years after the Rehnquist court had upheld it. For Bopp, the case was a critical victory—not just because it struck a blow to McCain-Feingold, but because it provided insight into the Roberts court’s leanings on campaign finance. It also revealed something important: a concurrence penned by archconservative Justice Antonin Scalia, who argued that the court should have gone further and struck down McCain-Feingold’s restrictions on unlimited corporate spending entirely. Scalia’s concurrence was joined by Clarence Thomas—unsurprising given his hard-line stance. But the third signature was the most intriguing. Anthony Kennedy, the former corporate lobbyist from Sacramento, had signed on. To Bopp, this was a flashing neon signal. Kennedy, like Lewis Powell decades earlier, could be swayed to go big. With the right case, Bopp believed, Kennedy could help deliver the conservative movement’s ultimate prize: the dismantling of decades of campaign finance restrictions in one fell swoop. The moment would come soon. In 2007, Bopp got a call from conservative activist David Bossie, president of Citizens United, with a provocative proposition. “I’m working on a movie called Hillary: The Movie,” Bossie told Bopp. Hillary Clinton, then a U.S. senator from New York, had recently announced her candidacy for president, and Bossie and his funders were eager to go on the attack. Bossie wanted to broadcast the 90-minute smear infomercial before the 2008 primaries. The problem: McCain-Feingold barred corporations from funding election ads in the final weeks before an election. And he didn’t want to disclose his donors. He asked Bopp to review the script and find a legal strategy to sidestep the rules. Bopp had a plan. Instead of waiting for the FEC to come after Bossie, Bopp filed a lawsuit preemptively, seeking a declaratory judgment that the film wasn’t electioneering. As expected, the lower courts rejected the claim. But that gave Bopp what he wanted: a path to the Supreme Court. As the case moved forward, Citizens United replaced Bopp with Ted Olson, a seasoned Supreme Court litigator. Olson framed the film as a documentary and cast the case as a First Amendment battle. Olson portrayed Hillary: The Movie as a piece of “documentary” journalism rather than a blatant political ad. He argued that the McCain-Feingold Act wasn’t designed to restrict films distributed through video-on-demand services and that the government couldn’t prove the movie posed any threat of corruption. Justice David Souter wasn’t convinced. Reading a series of quotes from the film, he pressed Olson: “Doesn’t this one fall into campaign advocacy?” The conservative justices, however, had a different agenda. Kennedy floated increasingly abstract hypotheticals, asking whether restrictions could apply to books or satellite-transmitted e-books. The government’s lawyer tried to redirect the conversation back to the questions at hand—whether corporations could anonymously funnel money from their coffers into election communications without restriction. But the conservative justices had already reframed the debate as a First Amendment question over book banning. This wasn’t the case Bopp had initially crafted, nor the arguments Olson presented, but it was exactly what the master planners on the court needed: a platform to begin dismantling campaign finance laws under the guise of defending free speech. After an hour of increasingly esoteric questions and hypothetical scenarios, oral arguments concluded. Chief Justice Roberts began drafting a narrow opinion that would grant Citizens United a win on narrow statutory grounds. However, Kennedy, never one to shy away from sweeping declarations, circulated a much broader decision—a blueprint to overturn Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce and McConnell v. FEC, landmark rulings that had previously upheld limits on corporate political spending. It was Kennedy’s draft that changed everything. According to court watchers, Roberts was so taken with it that he scrapped his own opinion and let Kennedy write the majority. This would not be a minor clarification of McCain-Feingold. It would blow a giant hole that big-money donors could flow through. Justice David Souter was reportedly furious. He had begun drafting a blistering dissent, calling out the majority for effectively inventing a new question in order to issue a sweeping decision that went far beyond the scope of the case. But before his dissent could see the light of day, Souter announced his retirement from the court. What happened next shocked even veteran court observers. Rather than issuing a decision, Roberts hit pause. He ordered a rare reargument and instructed lawyers from both sides to submit new briefs addressing completely different constitutional question: Did corporations have a First Amendment right to spend unlimited money in elections, so long as the spending was “independent” and not directly coordinated with candidates? By signaling its intent to tackle such sweeping issues, the court was positioning itself to deliver a truly transformative decision. When the court reconvened in September 2009, Justice Sonia Sotomayor had replaced Souter. Olson returned to the lectern with a new brief and a broader argument. It was no longer about Hillary: The Movie. Instead, it was about whether corporations had a fundamental right to spend unlimited money on elections. The government’s attorney tried to keep the case grounded: This was about a film funded by undisclosed donors, aired during a federal campaign. But the conservative majority was already down the rabbit hole, spinning hypotheticals about book banning and free speech. Advocates for reform warned that a decision for Citizens United would essentially turn American democracy into a corporate free-for-all. Public officials would become de facto employees of their largest donors, and elections would be determined by who could spend the most money. The question loomed: Was the Roberts court radical enough to go that far? On Jan. 21, 2010, Justice Anthony Kennedy provided the answer. “Political speech is indispensable to decision making in a democracy,” he wrote, “and this is no less true because the speech comes from a corporation rather than an individual.” But the opinion went even further: Only quid pro quo corruption counted as real corruption. According to Kennedy, access and other forms of political influence—like the kind Kennedy himself had facilitated as a young lobbyist in Sacramento—were not corrupt. It was the most radical redefinition of political corruption in modern history. And it came in a case that hadn’t even asked that question. In the 2010 midterms, dark money groups spent $134 million, a 427 percent increase from the previous cycle. By 2024, campaign spending had reached nearly $18 billion. Today, the logic of Citizens United so permeates American politics it’s easy to forget it wasn’t always this way. Lawmakers now treat chasing—or dodging—billionaire-funded super PACs as a core part of their job. Disclosure laws are eroding. And in the term that started this month, the Roberts court is set to weigh a case that could erase one of the last remaining guardrails. Kennedy’s new memoir may celebrate a life of moderation and pragmatism, but his most defining act is the radical and delusional Citizens United opinion, in which he unironically asserted that “independent expenditures, including those made by corporations, do not give rise to corruption or the appearance of corruption” and insisted that “the appearance of influence or access will not cause the electorate to lose faith in this democracy.” That ruling was the culmination of a decadeslong plot to turn elections into auctions, and transform political discourse into a one-way monologue by those wealthy enough to buy a megaphone to drown out the rest of us. The story of how corruption became legal in America isn’t just about memos, movements, and legal strategies. It’s also about seemingly technical moments inside the chamber, when a single justice fused his maximalist vision of free speech to the raw power of cold, hard cash. Kennedy is now trying to shape his legacy on his own terms, and he says he’s worried about the survival of democracy—but democracy is in crisis in no small part because of the decision he authored.