It can feel like it’s a big step to take for Michigan parents to start a conversation about suicide prevention with their kids.

But it could be the most important one.

September is National Suicide Prevention Awareness Month, and a list of resources may have appeared more than usual in school newsletters, mailers and conversations with education leaders, hoping to spread the word on often-underutilized resources available to K-12 students in need of mental health support.

Suicide is the 11th leading cause of death overall in Michigan and the second among children and young adults ages 15 to 24, according to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

For parents and caregivers, now may be a good time to broach the subject with their kids at home.

Make sure you’re well, and then, be straightforward

Sometimes for a parent, working with their child first means working a little on themselves.

Crystal Cederna, a pediatric and clinical health psychologist and associate professor at Michigan State University, said there’s a “huge parent mental health crisis,” as well as growing concerns about mental health among teens.

Parents should make sure they feel up to the conversation, first.

“What we know is when parents are not well, they’re not best positioned to support their kids’ health and wellness,” Cederna said. “So, not being afraid to seek our own therapy to learn any skills that we need to navigate the levels of stress and current world we’re living in will also be helpful to kids.”

Parents Jeff and Kristen Roberts started a nonprofit in 2019, two years after their son Miles, a 15-year-old student athlete at an Ann Arbor high school, died by suicide.

Since then, as they’ve grown the Miles Jeffrey Roberts Foundation, they said they’ve learned a lot about prevention and how to spread awareness about the issue. Now, when asked about bringing up the subject of suicide and mental health with kids, they say it’s best to be straightforward in an environment and routine that’s safe.

It’s important to understand the signs, Kristen said. But it’s also important to use the word — suicide, she said.

“Just being very open,” Kristen said in an interview Sept. 23. “And if they notice different things in their child, like spending a lot of time in their room, any of the big signs like giving things away, having a hard time with social media … that they be comfortable having the discussion that they’re noticing these things.”

Most experts seem to agree.

Spot the signs, especially post-pandemic

MindWise Innovations, a group that provides suicide prevention programming, lists other warning signs like major changes in behavior, appearance, eating or sleep, as well as sounding hopeless and overwhelmed and talking of death.

The group also tells parents and caregivers to acknowledge the signs and show their loved one they care.

Cheryl King is a professor of psychiatry at Michigan Medicine and a teen suicide prevention researcher at the University of Michigan. She said parents can keep an eye out for signs of withdrawal and isolation — something that affected young people and adults of all ages coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Possibly even from previously enjoyed activities and friends,” she said via email.

“It’s also good for us all to keep in mind that there is A LOT online — positive and negative — so we recommend parents set some boundaries regarding WHAT and HOW MUCH,” King added.

Locate all the necessary resources

Most school districts and community care organizations can link families up with mental health and suicide prevention resources.

Jeff Roberts said a lot of those existing supports don’t really have good public relations systems. People, he said, don’t always know what’s there.

“Parents like to think we can do it all, and so, they should know that those resources are out there,” he said. And parents should also learn to accept the help, especially among mental health professionals, social workers and other school leaders.

“Those people are trained to see warning signs and … present the right language, which is important,” Jeff said.

Like other suicide prevention organizations, the Miles Jeffrey Roberts Foundation highlights local, state and national resources.

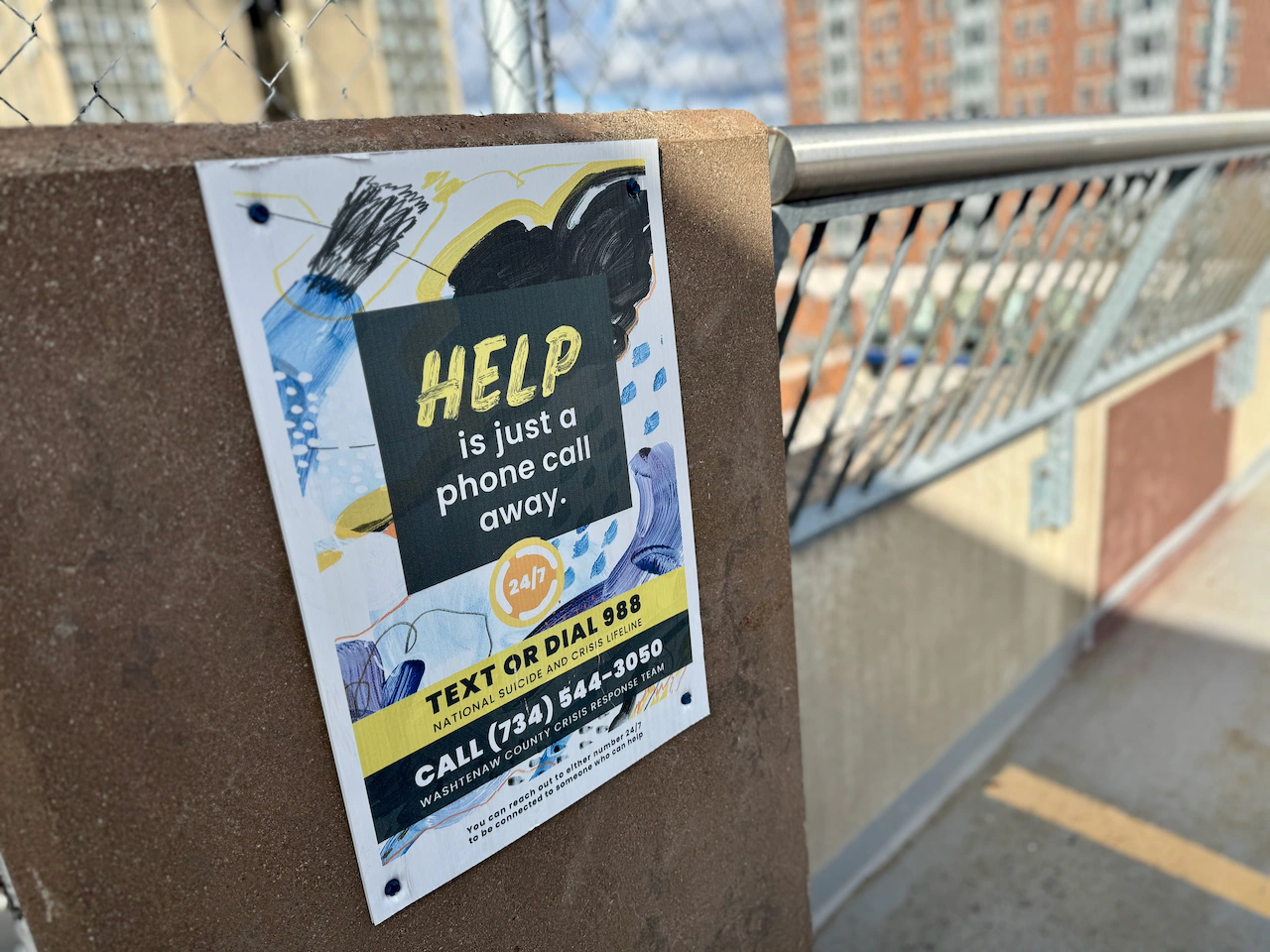

Outside of schools, many communities have underutilized Community Mental Health agencies. Michigan students also have access to a 988 suicide and crisis lifeline on student ID cards.

If you or someone you know is struggling, call or text 988 or visit the Lifeline Chat to connect with a trained crisis counselor.

Shore up your child’s social safety net

King said young people may need help stepping outside the comfort zone of their home.

“Some youth will benefit from more structured, adult-led social activities like a sports team, school club, or interest group,” she said, “as the adults provide some structure and emotional safety.”

When Kristen Roberts talks about the issue, she refers to a kids’ safety net — a community of adults who help look out for them.

Miles had a safety net, Kristen said, though he may not have been aware of it.

Nearly all prevention programs emphasize ensuring youth and teens contact an adult about mental health concerns, be they teachers, care professionals, a coach or other school personnel.

For more information, visit afsp.org.

Cederna said unconditional love, regular nutrition, warmth and comfort are among the best preventive measures for kids, calling them the “protective factor” that they can incorporate in everyday life.

“High parental monitoring, which is tricky, particularly with teens,” she said. “Because they love their privacy, and yet, what we know when there’s a good relationship between parents or caregivers and their kids, when parents are routinely checking in and inquiring how kids are doing … it improves and enhances that parent-child connection.

“And that’s been shown to be a good protective factor and buffer.”

Help them deal with stress, find joy

Once a problem is addressed and any needed treatment with mental health professionals is identified, there’s still more parents can do at home to help their children thrive.

Good nutrition, sleep and physical activity are often among the key health-enhancing behaviors in addressing psychological distress and wellbeing with adolescents.

Jeff Roberts references all three casually in conversations about setting up the right environment at home, as the Roberts took stock of the big picture with their family following Miles’ death in 2017.

He said it’s about helping kids feel like they’re headed in the right direction — something parents can do by spending time with the whole family.

“Kind of natural interactions,” Jeff said. “Whether that’s having a meal together, but it’s just routine, (or) interactions where you can have face-to-face conversations. You’re off your devices. You are commonly focused on something together and speaking honestly to each other.”

Kristen said it’s also about working on emotional regulation as a parent and sharing those strategies with their kids, especially if they’re being hit with stressors in life.

“If you don’t have the coping skills, your window of tolerance to handle those (is) really narrow,” she said. “So, the coping skills, working on meditation. Our son, our youngest, is really good about (that).

“When he’s having a hard time, he goes outside and just shoots baskets. Having those different toolkits, journaling, just being able to sit down and talk about it. And if you’re having a hard time, just helping each other to regulate so that you can have a really effective conversation.”

Anyone experiencing thoughts of suicide can seek help by contacting:

The 24-hour National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988

The Ozone House, a 24-hour hotline for youth, at 734-662-2222.

The 24-hour hotline at University of Michigan Psychiatric Emergency Services at 734-936-5900.

The Washtenaw County Community Mental Health crisis team at 734-544-3050.