Copyright Polygon

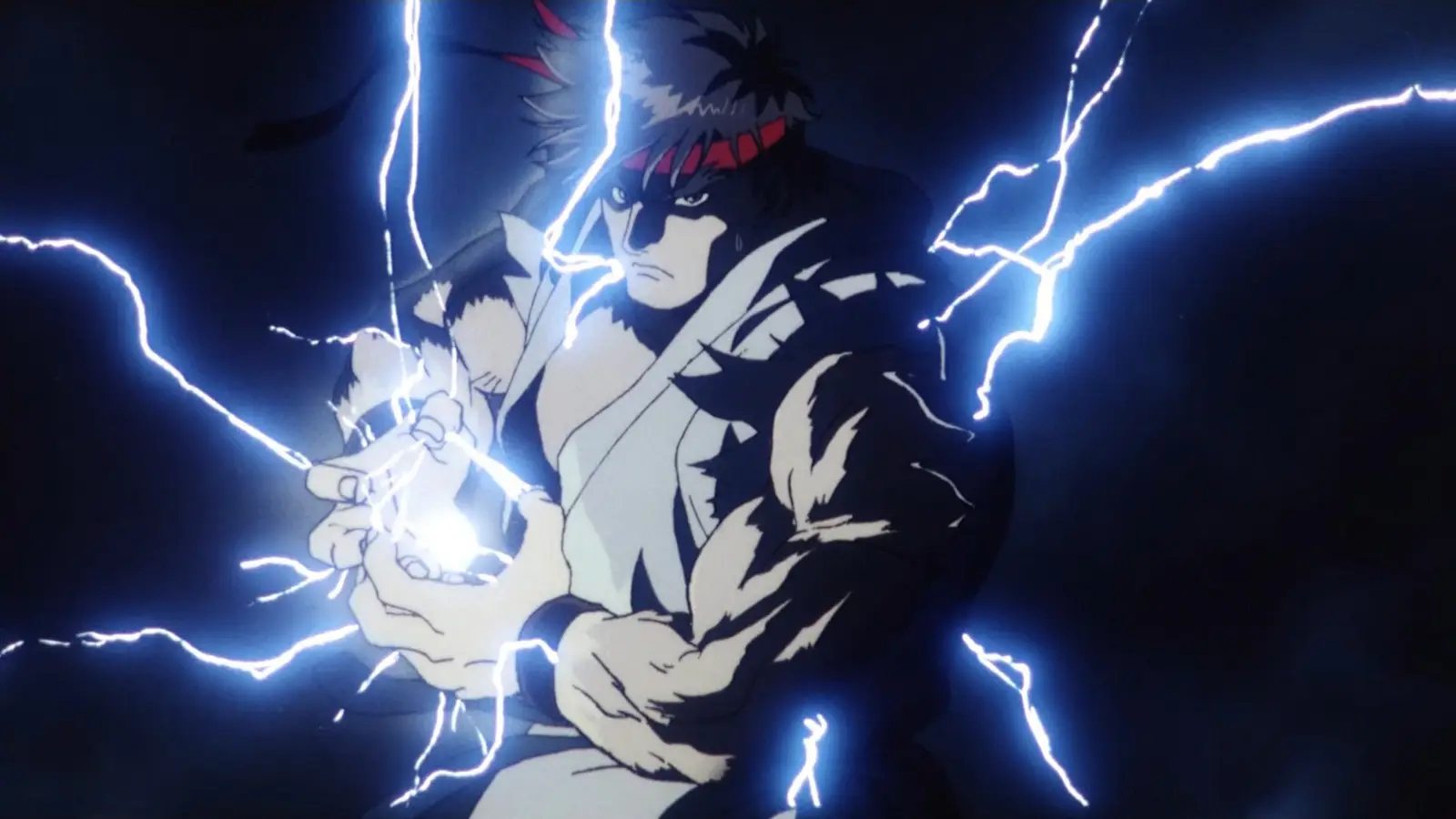

One of the fondest moments of my childhood was being genuinely terrified by the opening to Street Fighter II: The Animated Movie. By that point in my life, I’d played the Street Fighter games and was proudly wearing my puppy love for Chun-Li on my sleeve. The game's action-packed story never seemed outside my age bracket or consisted of any scary moments, until then. The 1996 anime film begins on an eerily deserted road at night. In a nearby field of grass, two fighters exchange blows. Unlike other action movies, especially the animated ones of the time, the brooding score’s volume is overpowered by the grunts and hits of the fighters, along with the sound of thunder as lightning pierces the midnight sky. Even the blades of grass in the wind echo louder than the guitar riffs playing in the background. Something about the darkly serious fight scenes felt so intimidating that I wondered if I had stumbled onto an animated movie too adult for me, as I often did at that age. Finally, I caught a glimpse of Ryu in the night, his red hachimaki flowing in the wind. That’s when I realized Street Fighter was a lot more than I gave it credit for. As an adult, I recognize the greatness of this scene for what it is: two non-traditional fighters brawling it out, not for glory, not for prize money, but as warriors seeking to discover who is truly the best. As a kid, I was too overwhelmed to understand what I had just witnessed. Street Fighter II: The Animated Movie draws heavily from the game’s narrative framework, yet it ultimately transcends its source material. By expanding on character motivations, relationships, and worldbuilding, the film not only redefined how fans perceive the Street Fighter universe but also set creative precedents that continue to shape the series today. What began as an adaptation evolved into a foundational text for the franchise’s tone, aesthetic, and storytelling style, starting with the opening scene of the movie. The original Street Fighter game, from 1987, establishes that Ryu and Sagat fought during the titular tournament. When Sagat went to help Ryu up, the darkness within, due to the Satsui no Hadō, made Ryu deliver an uppercut so devastating it left a permanent scar on Sagat, the catalyst for his long-lasting grudge. The film retcons their battle, opening with a reimagined showdown in which Ryu travels a great distance to take on Sagat’s challenge. They meet at dusk and begin their intense fight. We pick up with Sagat on the offensive, while Ryu feels out his opponent. Sagat, always the aggressor, unleashes the first projectile: a Tiger Shot, one that looks supremely more powerful than the ones he easily delivers in the games. Ryu stumbles out of the way to deliver a counter-attack, but Sagat grabs his opponent and tosses him to the side. Already, the battle positions Ryu as a calculating thinker who fights without emotion to hone his ability. Meanwhile, Sagat is a big brute: brash, overly emotional, yelling and aggressive, and never on the defensive. Ryu delivers his first signature attack, the Tatsumaki Senpukyaku, but two things were different about his spinning kick — he doesn’t yell out the name of the attack, and upon connection, there’s an emphasis on the blood Sagat spits up. This wasn’t like my Street Fighter at all. It was a more grounded, fast-paced, action-oriented version of what I knew, one that didn't shy away from blood and wasn't afraid to showcase how a realistic fight would unfold. There was no time to yell attacks. There was only time for action. As the fight continues and Ryu finally hits the ground, Sagat gets cocky, assured that he will be the victor after one crushing final blow. His gigantic frame leaps into the sky as he prepares to drive his knee into Ryu’s back. But Sagat doesn’t know what fans of the game knew well: you don’t jump when fighting against Ryu (or even Ken). Ryu counters with an anti-air attack: his signature Shoryuken uppercut, which splits Sagat’s torso and sends blood pouring out of the wound. His iconic scar is now born. Sagat sits on the grass, holding his chest, as Ryu remains in his stance, though visibly out of breath. Both men know the fight should end right here. Ryu has easily won the encounter, but Sagat can’t let it go. He stands, visibly gassed, and charges at Ryu. What happens next has stayed with me since I was a child and will probably continue to live rent-free in my head until the day I die. Ryu lets out a howl as he begins to collect electricity in his hands. It’s a soundbute and a visual that never fails to give me goosebumps whenever I see, hear, or even think about it. As a fan of the series, I knew what came next, but just like the Tiger Shot, this version of Ryu’s signature Hadouken looked and felt different, as if just one hit from it could deplete one’s health meter. As Sagat continues to advance and Ryu continues to charge the blast, triumphant theme music begins to play, culminating in Ryu sending the blast directly towards the screen, just as he does in the intro to Super Street Fighter II. For a kid who also grew up loving Dragon Ball Z, this was like watching Goku do the Kamehameha against Vegeta for the first time. My love for anime deepened right at that moment, and over 25 years later, everything from the movie’s influential story to its detailed animation continues to hold up. As the story unfolds, it becomes clear that many moments and details fans associate with the games originated in Street Fighter II: The Animated Movie. Its success inspired Capcom to develop the Street Fighter Alpha game series, expand character backstories, and further embrace anime influences. The Alpha games even modeled their bulkier character designs after the film’s look. The grassy field where Ryu battles Sagat reappears in Street Fighter Alpha 2 and later as a DLC stage in Street Fighter V. Cammy’s signature move of discarding her red cloak, first seen here, carries into X-Men vs. Street Fighter. (Her assassination attacks from this movie later appear in Street Fighter × Tekken, and Street Fighter 6.) The film also established Chun-Li and Guile’s partnership, while the concept of Violent Ken traces directly back to its finale.